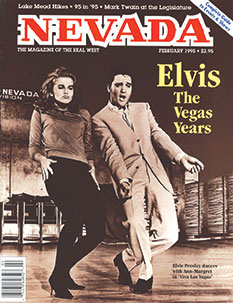

Elvis: The Vegas Years

February 1995

Elvis Presley, who would have turned 60 in 1995, once reigned in Las Vegas. Some say he still does.

BY MIKE WEATHERFORD | January/February 1995

But on opening night Elvis went down “like a jug of corn liquor at a champagne party,” according to Newsweek.When Elvis Presley made his Las Vegas debut in 1956, the 21-year-old marvel from Memphis was driving a wedge between the generations with “Heartbreak Hotel.” The booking at the New Frontier was an attempt by his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, to break Elvis out of the Southern honkytonk and state-fair circuit and give him national credibility. Elvis was billed in newspaper ads as “The Atomic Powered Singer” and an “extra added attraction” to Freddy Martin and His Orchestra and comedian Shecky Greene at the Strip hotel.

“He was kind of weird looking for those people,” recalls Freddie Bell, a lounge singer performing at the Sands at the time. “He had the sideburns, and that hair.” And he was singing rock ‘n’ roll, loudly, in Sinatra’s town.

In time Elvis, who would have turned 60 on Jan. 8, became an indelible presence in Glitter City. He last appeared live in Vegas in 1976, but evidence of Elvis is everywhere. If he could wander around Las Vegas today, he would see his visage in nearly every gift shop. He would bump into karaoke-singing clones of himself on sidewalks along the Strip. Elvis could see “tributes” to him any night of the week. He might see entire conventions of impersonators or watch Flying Elvi parachuting from airplanes into casino parking lots.

Las Vegas plays a role in all three acts of his short, larger-than-life story. There was his 1956 debut, where he tested the mainstream waters. Later it was Las Vegas where he came to play and make movies, and where he got married. Las Vegas is most associated with the final act—Elvis making a triumphant return to live performing, only to become an isolated, drug-ravaged self-parody.

In his glory years, when Elvis was making his twice-annual visits, his fans would crowd the city, seeking an audience with the King.

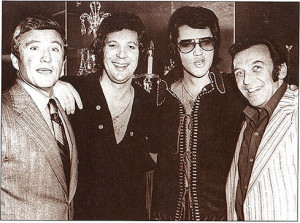

“Sinatra was a show. Elvis was a happening,” says Joe Guercio, the Las Vegas Hilton musical director and orchestra leader for Elvis’ Vegas shows and tours in the 1970s. “It was another world. You can’t get that going again.”

“They loved what he did. They loved what he stood for. He was America,” says Sammy Shore, the comedian who opened Elvis’ shows at the International Hotel. “He was a Southern boy who became the world’s idol.”

Of course, Elvis’ success in the desert was hardly presaged by his New Frontier debut in April 1956. On opening night, Las Vegas News Bureau photographer Jerry Abbott recalls, “I shot one roll of film on him and thought, ‘this is going nowhere.”‘ Abbott decided to use the rest of his film on Shecky Greene.

Las Vegas Sun columnist Bill Willard wrote, “For the teenagers, the long, tall Memphis lad is a whiz; for the average Vegas spender or showgoer, a bore.” Today Willard recalls with a laugh, “I predicted a nowhere ending for Elvis as far as Vegas is concerned.”

During his Vegas stay, Elvis caught Freddie Bell’s lounge show at the Sands. Later Bell gave Elvis a valuable parting gift. Bell says Elvis was so impressed by “Hound Dog,” Bell’s toned-down version of a song first recorded by Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, that he gave the Colonel a copy of the single that had been a regional hit for him in the East. Bell hoped that if Elvis recorded it, he might benefit when his own version was released on an album. Alas, few people today have heard Bell’s recording, while Elvis’ “Hound Dog” remains one of rock’s most memorable songs.

When the two-week engagement ended, Elvis left to star in his first movie, “Love Me Tender,” and the Strip went back to nightclub fare. Las Vegas Sun columnist Forrest Duke summed up the problem: “With an audience of jaded adults … he’s not quite in his element.” Then again, Duke noted with foresight, “Who needs jaded adults? Elvis Presley?”

Outside the Nevada club scene, Elvis became a major star. He recorded new hits like “Jailhouse Rock” and “Teddy Bear,” purchased Graceland, spent two years in the Army, and reported for duty in a string of cheesy movies.

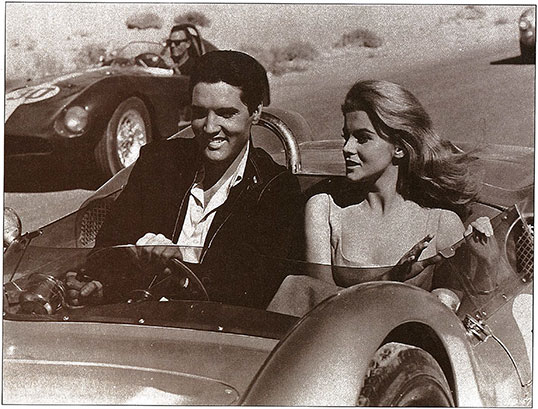

Perhaps the best of the lot was “Viva Las Vegas,” which was filmed in and around the Flamingo in the summer of 1963. In Elvis, the controversial Presley biography, author Albert Goldman claimed that the pairing with the vivacious Ann-Margret led to “the only authentic romance in Elvis’ long career of dating Hollywood actresses.”

That would explain the chemistry that elevates Viva Las Vegas above its typically insipid plot, which—surprisingly—has little to do with gambling or show business. Instead, Elvis is the singing racecar driver Lucky Jackson, who woos Ann-Margret as Rusty Martin, the Flamingo’s pool manager, while preparing for the (fictitious) Las Vegas Grand Prix. Although many of the indoor sequences were shot on MGM sound stages, the movie shows amazing scenes of a younger, roomier Las Vegas with low-slung hotels, classic marquees, and acres of barren land around the old convention-center rotunda. The climactic race stretches improbably from Fremont Street to Hoover Dam and Mount Charleston.

Complicating matters was the fact that Elvis was already attached to Priscilla Anne Beaulieu, whom he had met while stationed in Germany. Priscilla had moved into Graceland only a few months before.Ann-Margret confirmed their longrumored off-screen romance in “My Story,” her 1994 autobiography. She wrote, “We were indeed soul mates, shy on the outside, but unbridled within. We both lived on the edge and we were both self-destructive in our own ways.”

Freddie Bell remembers that “a lot of movie stars” were in Elvis’ company when he and his entourage made their rest-and-recreation visits to the Sahara between films. The Sahara was owned by Milton Prell, the Colonel’s friend and Palm Springs neighbor, and was “a swinging hotel at those times,” Bell says. Elvis often checked out Bell’s lounge show but would sneak out when Bell did his Elvis impressions. “He was afraid I was going to introduce him.”

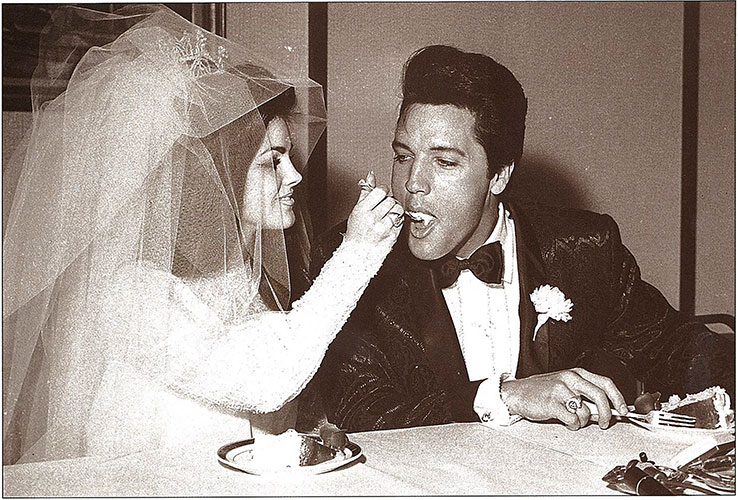

Whatever happened between Elvis and the Hollywood starlets, it was Priscilla whom he married in Las Vegas on May 1, 1967. She was 21, and he was 32. The Colonel made the arrangements, and Prell hosted the wedding at his new hotel, the Aladdin. (The exact location is a matter of dispute today among hotel officials talking about making it a tourist attraction.) The ceremony was performed before a few friends and relatives in Prell’s private suite before the party opened up to a celebration breakfast of 100 friends and guests.

Marriage and the imminent birth of daughter Lisa Marie aside, 1967 was not a good year for Elvis Presley. The Beatles and Rolling Stones had given rock ‘n’ roll a new direction and made soundtrack fluff such as “Do the Clam” seem silly and anachronistic. Elvis’ yearning to restore his credibility as a live performer led him to do a highly popular TV special, called the Singer special, in 1968.

Lamar Fike, now a Nashville country-music agent and publisher, was one of Elvis’ circle of friends known as “The Memphis Mafia.” He remembers the first talk of playing Las Vegas again.

“We had just finished the Singer special,” Fike says, “and had flown into Vegas for a rest, because we’d worked real hard on that. The Colonel was in the front seat of the limo with his driver, and I was in the back with Elvis. The Colonel turned around with his cigar and said, ‘You know, we can take that show you just did and put it in Vegas and make a lot of money.’ Elvis looked at me, shrugged his shoulders, and said, ‘Sounds like we’re playing Vegas.”‘

By the summer of 1969, Kirk Kerkorian was ready to open the International Hotel. With 1,519 rooms, it was the largest resort hotel in the world. To give it a proper opening, Kerkorian hired two of the day’s biggest stars: Barbra Streisand and Elvis Presley.

It was one of many smart moves the Presley camp made in preparation for Vegas.But who would go first? Fike doesn’t remember it being an issue of importance, but Bruce Banke, the hotel’s publicist at the time, recalls that because construction wasn’t finished by opening day, “the Colonel said, ‘Open with the girl and we’ll follow her. Get the kinks out of the showroom.”‘

“Elvis Presley’s preview opening was as warm for us as Barbra’s was cold,” proclaimed Joe Delaney, the Las Vegas Sun entertainment critic. Delaney recently explained, “Instead of Barbra mixing it up, she came out very seriously and began singing [ songs from the musical] ‘Jacques Brel’ and things that hadn’t really caught on at the time.”

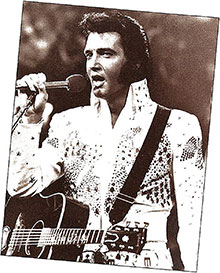

Elvis, however, had been studying Vegas. The Elvis who strode onstage at the International on July 31, 1969, was an all-round entertainer fronting a rock band polished and magnified by horns and strings.

Still, there were some pre-show jitters. “Elvis was nervous because the last time he was in Vegas he lost his ass and didn’t do a damn thing,” says Fike. “It rattled him. He was bothered by it.”

Sammy Shore had been tapped as an opening act after Elvis saw him open for young Welsh heartthrob Tom Jones. (Goldman’s book claims Presley stole his entire Vegas-era stage persona from Jones.) After walking onstage, Shore discovered his microphone was dead. When he was handed a second mike, he pretended that one was off, too. The gag won the crowd over for his 25-minute set. “It was so easy to bomb in that room,” Shore says of the 2,000-seat showroom, the largest ever built in Vegas.

As Shore walked off, Elvis was standing in the wings waiting to go on, and he extended a hand. “His hand was clammy,” Shore recalls. “He was as nervous as I was.”

A drum beat ushered Elvis onstage. Clad in black with a guitar slung around his neck, he struck a familiar pose and intoned: “Well, it’s one for the money, two for the show, three to get ready, and go, cat, go!”

Elvis churned and burned his way through “Blue Suede Shoes” and other hits like” All Shook Up,” “In the Ghetto,” and “Can’t Help Falling in Love.” He closed the 15-song performance with a six-minute version of his most recent single, “Suspicious Minds.” During the show he told the audience of invited guests, “It’s the first time I’ve worked in front of people for nine years, and it may be the last. I don’t know.”

The audience had no such doubts. The show was galvanizing. Elvis’ stepbrother Billy Stanley recalls in his autobiography that “we were seeing a whole new side of Elvis …. More than a decade had been erased in one night’s performance; the ‘rebel king’ was back on top of his profession and on top of the world.”

Legend has it that the very next day the Colonel and hotel president Alex Shoofey struck a five-year deal, offering Elvis twice-annual engagements at $125,000 per week. Bruce Banke says there was never a signed contract, only a handshake deal. No matter. Elvis’ annual “Summer Festivals” in August and return engagements in February soon became a bonanza for both parties.

If Elvis’ timing in 1956 was poor, in 1969 it was perfect. The International, which became the Las Vegas Hilton in 1971, was huge but lacked a theme like most major resorts have today. It was more of a convention hotel, sharing a parking lot with the Las Vegas Convention Center. Elvis simultaneously gave the Hilton a theme and, twice a year, a convention.

“His audiences were now ready,” Bill Willard says of the ’70s. “The kids had grown up and now had the nostalgia thing going.” They still screamed and clawed their way to the stage in hopes of being anointed with a kiss and a scarf while Elvis crooned “Love Me Tender.”

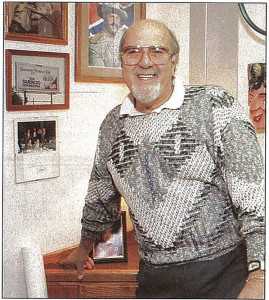

The night before Elvis’ first show, the Colonel—who is 85 and lives in Las Vegas today—would wait until people entered the showroom for the preceding headliner’s last show. Then he would have every square inch of the hotel plastered with Elvis posters. “By the time people came out, they’d be walking in to a different casino than when they came in,” Banke says. “He prided himself on never leaving an empty spot.”

Sinatra and the Rat Pack still drew the heavy players, but Joe Guercio recalls that Elvis “put bodies in chairs”—100,000 of them for each engagement, counting returnees (like Deadheads, Elvis’ fans tried to catch as many shows as possible). “It will never be again. I don’t care how big the star is,” says Guercio, now entertainment chief at Arizona Charlie’s, of the commotion surrounding Elvis’ shows.

Las Vegas was good for Elvis—at first. For two years he seemed happy to be back in direct contact with his fans, and the Hilton gave him a home base when he wasn’t touring. The hotel’s 30th floor Imperial Suite was intended as a retreat for all its headliners, but eventually it became known as “The Elvis Suite.”

Whenever Elvis flew into town, road manager Joe Esposito would phone ahead so hotel officials could dispatch limousines to the Howard Hughes Charter Terminal. By the time the limos got to the private airfield, “there’d be 500 fans there,” Banke recalls with a laugh.

“I thought, ‘How do they know this?’ People always seemed to know what was happening.”

The limos then would whisk their passengers to the hotel’s north laundry entrance.

Elvis was constantly surrounded by his entourage, and life in the Hilton penthouse was a strange mixture of hedonism and hominess. “He used to want everybody in his suite every night,” Guercio says, but often “they would sit around and play gospel music.”

Elvis remained the polite Southern boy. “He always called me ‘sir’ even though he was a year older,” Banke recalls.

Elvis and the boys had a penchant for pranks. Guercio once jokingly complained the billboards always said “ELVIS” and didn’t mention the band. Soon he discovered a billboard near the Strip that said, “The Joe Guercio Orchestra,” with the word “Elvis” in smaller letters in one corner.

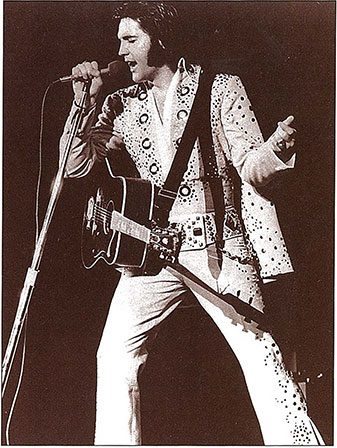

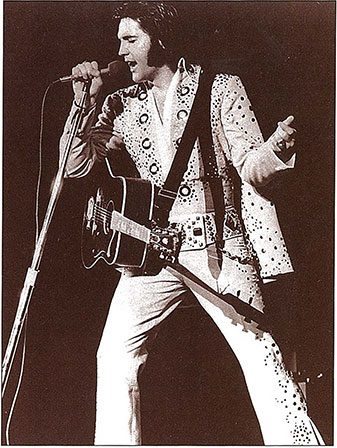

The show reached new levels of spectacle. His black karate outfit was replaced by a white jumpsuit adorned with sequins and upturned collar. Guercio came up with a theme fit for a king one night when he and his wife went to see a reissue of 2001: A Space Odyssey. During the opening sequence set to Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” his wife leaned over and said, “Don’t you get the feeling Elvis is about to walk out?” From that point on, Elvis never walked out to anything else.

However, no one was laughing in January 1971 Memphis newspaper revealed Elvis had received death threats. Security was unusually tight, and “the whole room was in chaos,” Shore said. “I made it funny. I kept saying, ‘Remember I’m just a comic…Don’t shoot.’ “

Two years later, Elvis got to display his karate expertise four men rushed the stage from their ringside seats. Elvis sent the first one flying into the audience. The four later filed suit, claiming they were just trying to shake hands.

“Everyone was riding a crest,” Shore says. “No one thought it was ever going to end. I remember feeling like I never wanted this to stop.”

Elvis continued to ride the wave, but there signs of trouble. Shore, who in a misunderstanding left the show to play the Hilton’s lounge in 1972, noticed a change in Elvis onstage.

“A few years later when I went to see [the show] I felt really sad,” Shore recalls. “He just didn’t’ care anymore. It was like showing up and doing a job now. I thought ‘Why are you letting this all slip away?’ ”

Bill Willard found the shows becoming more ritual in the summer of 1973. He wrote in Variety “It’s déjà vu time—everyone’s been there before, even to the ‘new’ tunes inserted.”

Elvis’ admitted loss of enthusiasm for Vegas was compounded by his divorce from Priscilla in October 1973. Later some of his friends said that, despite his obvious role in the split, the divorce was exceedingly painful for Elvis and marked the beginning of his great decline.

In August 1974, citing pneumonia, Elvis canceled Hilton shows for the first time—he had missed only five show dates in his entire career, he told reporters. The next summer he canceled most of a Hilton engagement to fly back to Memphis to be hospitalized for “fatigue.” He gained weight, and his attitude changed.

“By 1975 he was bored,” says Joe Delaney, who wrote his first less-than-glowing column after Elvis wisecracked and insulted band members for most of the show before cutting it short. “The attitude was just terrible,” Delaney says.

Several authors share biographer Goldman’s view that Elvis need a long break from Vegas and concert tours but felt it necessary to continue because of debts mounting from excessive spending and other business pressures.

Several authors share biographer Goldman’s view that Elvis need a long break from Vegas and concert tours but felt it necessary to continue because of debts mounting from excessive spending and other business pressures.

Two shows a night-almost unheard of in modern-day Las Vegas-were still the norm for Elvis, even in the later years. “If somebody did it now, they’d die onstage,” Lamar Fike says. “It was the most cruel thing I’ve ever seen in my life. It’s a wonder we even lived through it. That probably killed him more than anything did.”

Public interest again waned. “The last two years he still filled the house, but it was the die-hards at that point,” Delaney says. On opening night, Dec. 3, 1976, comedian Jackie Kahane, Shore’s successor, was finishing his routine when someone whispered through the curtains, asking him to stretch his act. Elvis came onstage late. “He is still a little heavier than he should be but not as heavy as on his previous visit. The capacity crowd could care less,” Delaney wrote.

The 11-day, 15-show engagement ended on Dec. 12. It was the last Las Vegas would see of the real Elvis Presley.

Joe Guercio was shopping at the Boulevard Mall before joining the band in Portland, Maine, when he heard the news.

Bruce Bartke took a call from an Associated Press reporter who said there were unconfirmed reports that Elvis Presley had died. “I told him that with certain stars, rumors start all the time. ‘If you hear anything else, call me back.”‘ When the reporter called back, Banke could hear bells in the background, sounding the “urgent” code on the AP’s old teletype machines.

Bartke barged in on a meeting between Barron Hilton and the hotel’s executive staff. “I must have been white,” he says. “I hadn’t been in the room a minute when the phone rang. It was Colonel Parker calling Barron to confirm it.”

Bartke barged in on a meeting between Barron Hilton and the hotel’s executive staff. “I must have been white,” he says. “I hadn’t been in the room a minute when the phone rang. It was Colonel Parker calling Barron to confirm it.”

The cause of Elvis’ death on Aug. 16, 1977, remains an issue of speculation and controversy. Apparently he died of heart failure at Graceland, a victim of prescription drugs, fatigue, and the burdens of celebrity.

Today, it may be hard to imagine the King as a 60-year-old rock star with a senior-citizen discount card, or as a portly sexagenarian singing “Heartbreak Hotel” to a full house of gray-haired fans.

But even now he remains a ubiquitous presence in Las Vegas. Inside the Hilton, a statue of Elvis is an object of homage and curiosity. You see him everywhere, in tribute shows and even wedding chapels.

He is still the young Elvis struggling in his debut, and the older Elvis triumphant in his comeback. In Las Vegas, Elvis lives forever.

This story was first published in the January/February 1995 issue of Nevada Magazine.