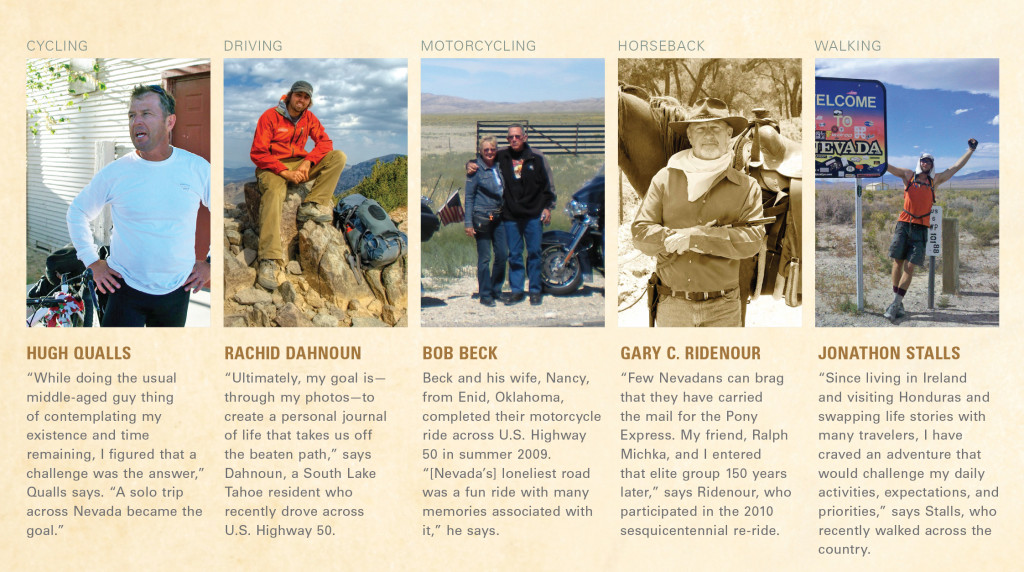

‘Lonely’ Perspectives: 5 Trips Across Highway 50

‘Lonely’ Perspectives: 5 Trips Across Highway 50

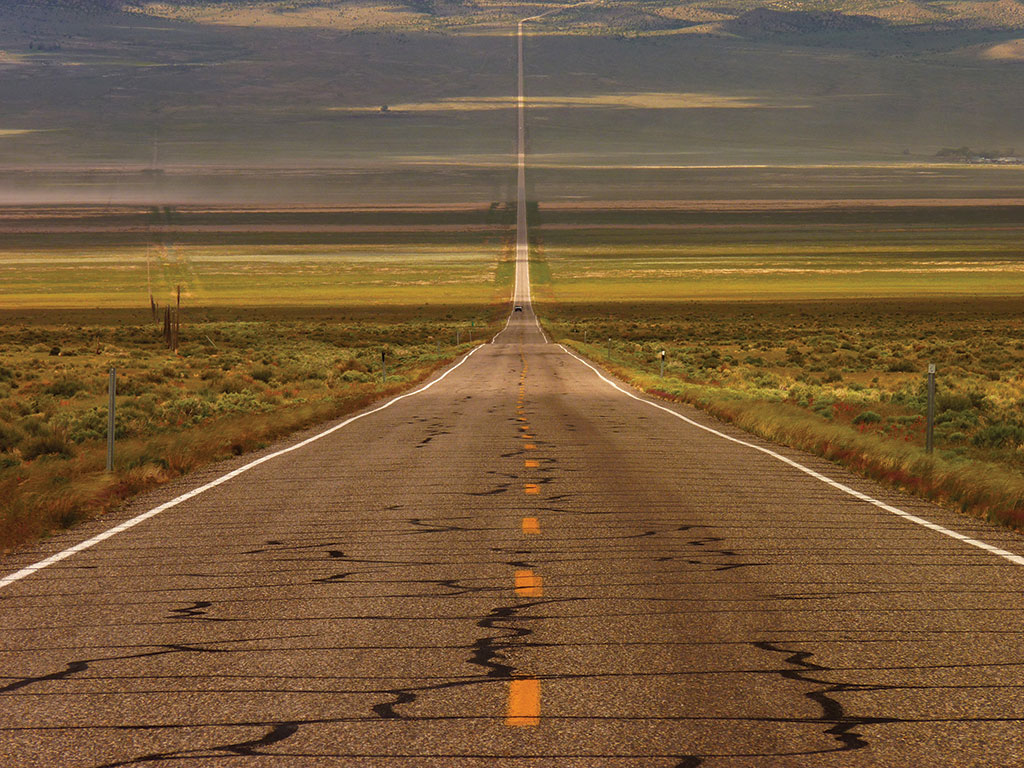

By auto, bicycle, foot, horseback, motorcycle—no matter how you choose to cross it—U.S. Highway 50 and central Nevada are food for the soul.

(This story originally appeared in the March/April 2011 issue)

CYCLING

BY HUGH QUALLS

DAY 1

A little more than 400 miles, 12 summit passes, and six days to do it. I would make it or die trying. In battling headwinds (as I would five of the six days), that death nearly came on the first day. My family and friends dropped me off near the Utah border, about a mile from the Border Inn on “The Loneliest Road in America,” U.S. Highway 50.

My pre-trip calculations made it all sound so easy: average 8 mph, and each day’s destination would be reached with minimal effort. Not considered in my faulty reasoning were the prevailing winds, almost always blowing from the west. Near the top of my first summit, Sacramento Pass, I had my initial encounter with the angry wind god, as I came to know him.

DAY 2

Good friends and a good night’s rest in Ely worked wonders. The next morning, Labor Day (Sept. 6) 2010, I was up early and eager to pedal all the way to Eureka. Yesterday’s misery was forgotten—at least mentally. My back, legs, and hands were sore, but I hoped that would pass after a few minutes on the road. I figured the only way this trip would succeed was if I kept moving, working through the agony, discomfort, and pain.

Eureka turned out to be quite popular the evening I coasted in—no vacancies. I was too tired to put up my tent and wanted a long hot shower. The merciful proprietors of the Best Western must have taken pity on me (no doubt I was pitiful looking) when they opened the historic Jackson House Hotel, built in 1877. Good food at the local Mexican restaurant and a few beers brightened my mood, and I slept well that night.

DAY 3

After a quick breakfast provided by the pleasant hotel hosts, I was on the road early for the next leg to Austin, about 70 miles. Fall was two weeks away but certainly in the air. I put all my layers on and pedaled west, thinking about a moment of ugliness the previous day. As I was about to begin the long, steep climb up Pinto Summit, trying to avoid the shoulder rumble strip and soft sand just to its right, an old pickup passed by much too close. The truck slowed as it veered in front of me. The passenger stuck his upper body out the window as he unloaded a tirade my direction. What I could understand, heavily sprinkled with profanity, was that I was a traffic hazard (my words) and to stay off the road. Believe me, I very much wanted to be off the road at that moment.

DAY 4

I was coming off a good night’s sleep in my ultra-light backpacker tent; my only neighbors the previous night at Bob Scott Campground were a few singing coyotes in the distance and a couple of bats darting about in the moonlight. The night started out clear, then clouded up—a sign of things to come this day. It was a warm morning due to the cloud cover, but, as I made coffee, it was certain that riding in the rain awaited.

I was coming off a good night’s sleep in my ultra-light backpacker tent; my only neighbors the previous night at Bob Scott Campground were a few singing coyotes in the distance and a couple of bats darting about in the moonlight. The night started out clear, then clouded up—a sign of things to come this day. It was a warm morning due to the cloud cover, but, as I made coffee, it was certain that riding in the rain awaited.

If you haven’t been to the bar/restaurant/motel that is Middlegate, then you have lived only half a life. Pulling up to the hitching post rail in Spandex on a 27-speed bike loaded with panniers is probably not how you want to arrive (dually flatbed pickups with hay bales are the rides of choice around these parts).

I was greeted warmly nevertheless. This was my stop for the night, and with the rain, I rented one of the motel rooms. Given that I was the first guest of the evening, I was handed the keys to the “Middlegate Suite” at no extra charge. I quickly put my bike and gear inside the room and headed back to the bar for good company, a tasty meal (taco night special), and a few beers.

DAY 5

By 6:30 a.m., I was pedaling up the long grade that is State Route 361, through Gabbs and over a couple of passes, then downhill to Luning and U.S. 95. An early start was required as 88 miles separated me from Hawthorne, my day’s destination. Friends and family were expecting me in time for dinner at the pizza place in town, and I didn’t want to disappoint them. My previous best had been 77 miles on Day 2.

Again, the wind. What should have been an easy 90 minutes into Hawthorne turned into 2.5 hours. I had no choice but to bear down and pedal until I was greeted by a long flat section alongside the Hawthorne Army Depot, as I made my way to the only stoplight on U.S. 95 between Fallon and Beatty. I dove into pepperoni and a pitcher of beer without guilt, in the back of my mind thinking about my final day of riding.

DAY 6

“Do or do not; there is no try.” Yoda’s philosophical advice to Luke Skywalker had become my motto for this trip. I was 56 miles from finishing. The end was near, and like my ride in the rain with the wind at my back, the thought of this adventure coming to an end saddened me. What had hurt the day before hurt even more so today; I was exhausted in every way possible as I made the very long (27 miles) climb on State Route 359 to Anchorite Pass, near the California state line.

The end was in sight. I could see it draw closer with each rotation of the wheels, each turn of the pedals. I didn’t want it to end but was elated nevertheless. It took a full two weeks for my tendons to return to normal; the outside two fingers of each hand are numb to this day.

Was it worth it? Without question, and I am already planning next year’s trip.

DRIVING

BY RACHID DAHNOUN

Driving across the Silver State on Highway 50 is a spectacular and surreal experience. The wide-open spaces, coupled with the rich history of the route, make it a one-of-a-kind journey. Every time I make the drive, it’s easy for me to picture a Pony Express rider blazing across the vast landscape or a group of settlers traveling to their next camp. If you are looking to experience the Wild West, this is it.

My journey begins at my home in South Lake Tahoe. I pass through Stateline, Carson City, and make my way toward Fallon. Once Fallon is in my rearview, my adventure is truly underway. Heading east, it becomes clear why they call this “The Loneliest Road in America.” It will be more than 100 miles until I reach the town of Austin; not to imply there is nothing to see along the way.

On the road to Austin I always stop and check out the 8,000-year-old petroglyphs at Grimes Point, the famous Sand Springs Pony Express Station near Sand Mountain, and my personal favorite, the shoe tree (a lone cottonwood adorned with hundreds of pairs of shoes from generations of Nevada travelers; the tree was cut down by vandals since Dahnoun wrote this). In addition, I consistently find myself pulling over to photograph the hundreds of beautiful vistas that perpetually appear before me. To stop on the side of a major road, look around at miles of open space, and not see or hear a single car or person makes it a wonderful place to clear your head.

Arriving in historic Austin, I typically enjoy lunch at the oldest hotel in Nevada, The International. The owner, Vic Antic, like many people living here, moved to Austin to get away from it all. He thoroughly enjoys the peace and quiet of small-town life.

Leaving Austin, my next stop is Eureka, home to the famous Eureka Opera House, the memorable Jackson House Hotel, and the Eureka Sentinel Museum. The museum is the former site of the Eureka Sentinel newspaper and features a complete pressroom from the late 1800s. Being a photographer and writer myself, it’s a treat to see and learn about the old equipment that shaped our modern media.

Further down the road in Ely, I proceed to the Nevada Northern Railway Museum to see an authentic steam engine in action. Surrounded by towering mountain peaks, it feels like I’m on the set of a Hollywood western. Tired from a long day of driving, I check in at the historic Hotel Nevada knowing that when I wake up, I’ll be traveling to my most anticipated destination.

Further down the road in Ely, I proceed to the Nevada Northern Railway Museum to see an authentic steam engine in action. Surrounded by towering mountain peaks, it feels like I’m on the set of a Hollywood western. Tired from a long day of driving, I check in at the historic Hotel Nevada knowing that when I wake up, I’ll be traveling to my most anticipated destination.

Great Basin National Park is the only national park located entirely within Nevada. Lehman Caves are the park’s most popular attraction and well worth the $10 entry fee (for a 90-minute tour). I also recommend taking the Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive to access the Bristlecone and Glacier Trail. This 4.6-mile roundtrip hike takes me to a large grove of Western bristlecone pines, considered the oldest living organisms on earth. At the trail’s terminus, I gaze upon the only glacier in Nevada and stand in a massive cirque beneath Wheeler Peak, the second-tallest peak in the state at 13,063 feet.

Traveling The Loneliest Road in America is so much more than just a drive across Nevada. Every time I make the journey I am awestruck by the history, scenery, and people I meet along the way. With our world ever crowding and open space becoming more of a premium, this iconic American highway allows us a glimpse at a natural landscape virtually unaffected by man.

MOTORCYCLING

BY BOB BECK

My wife and I spent the majority of 2010 participating in a Harley-Davidson Owners Group (HOG) ABC’s of Touring game, collecting points for visiting various states, Canadian provinces, cities, counties, various Harley-Davidson sites, and state HOG rallies. One of our planned rides was from our home in Enid, Oklahoma, to the Oregon HOG rally. We pefer to travel mostly on scenic highways, rather than interstates. During our research, we found the Nevada Commission on Tourism’s Highway 50 Survival Guide and included it on our route to Welches, Oregon.

My wife and I spent the majority of 2010 participating in a Harley-Davidson Owners Group (HOG) ABC’s of Touring game, collecting points for visiting various states, Canadian provinces, cities, counties, various Harley-Davidson sites, and state HOG rallies. One of our planned rides was from our home in Enid, Oklahoma, to the Oregon HOG rally. We pefer to travel mostly on scenic highways, rather than interstates. During our research, we found the Nevada Commission on Tourism’s Highway 50 Survival Guide and included it on our route to Welches, Oregon.

While cruising west on “The Loneliest Road in America” from Ely to Eureka, we were about 30 miles east of Eureka when we passed a group of bikers headed the same direction. As is the biker custom, we waved as they passed. About three to four miles later, I noticed a biker pulling up next to me in my rearview.

Rather than pass, the biker pulled up next to me and stayed close on my left shoulder. As I looked over to see why the biker had not passed, there is this guy with a huge grin on his face. After a second, I recognized my co-worker and friend Terry Johnson.

We pulled off the road and talked for a bit, laughing the whole time. Terry, in a roundabout way, was returning from the Sturgis, South Dakota rally. He related that, when we passed each other, he recognized the color of my bike. What are the odds of something like that happening?

Almost 1,500 miles from home, we ran into each other on the loneliest section of road in America. The chance meeting has left my wife and me talking and smiling about it ever since.

HORSEBACK

BY GARY C. RIDENOUR

…June 9 (2010) found us waiting on the dusty Fort Churchill trail for the Pony Express re-riders to appear and put the mochila over our saddles and send us off. The mochila is a large piece of leather with a cutout in it to allow it to be placed over our saddles. The cantinas, or mail pouches, were sewn into the mochila. Two are in front of your legs, and two are behind them. I decided this was a good design to keep us in the saddle and would act as a slide in case we went sideways.

Re-ride participants wear a black or brown hat, a red shirt, and a yellow bandanna. Some still carry 1860-replica pistols. My friend and fellow re-ride participant Ralph Michka and I decided to skip the guns for fear they would bounce out—or we might shoot ourselves because we forgot to unload them.

Without any fanfare or a shot of Gabby Hayes yelling to The Duke, “They’s a’comin’ lickity split like the devil is a chasin’ ’em!,” Erika and her dad could be seen coming around the bend. We threw our cell phones and other personal items in our trucks. Behind the riders was an SUV followed by a caravan of trucks and trailers of previous riders, who would follow the rest to Fort Churchill. I held my horse’s bridle as some people from the lead SUV transferred the mochila. I mounted and saw that Ralph was already down the trail. I got on my horse. Quietly, we began our trot into history.

Along the way we rode through a military tank test range. The chain-link fences and the old tires, rims, and various mechanical parts piled against it spooked the horses. We reached a small puddle across the trail. The horses balked. We tried every trick. Frustrated, Ralph slid down the side of his horse and led the animal toward the puddle without difficulty.

I heard someone behind me. I turned to see a young man with unruly hair, dressed in the proper attire for the time period of 1860. He said, “They’s spooked by the fences and now the puddle. Try and follow the other guy. His horse has it.”

Ralph led his horse through. My horse jumped the puddle. I was sure the guy behind us spooked the horses into moving. Sometimes that works. There seems to be no solid rules for horse behavior.

I started to trot and looked back, but the stranger was gone. I rode up to Ralph and did my Slim Pickens impression: “What in the Wild, Wild World of Sports is a goin’ on here?” Ralph shrugged. Proudly we rode into our exchange area smiling.

Later, at Fort Churchill, I asked Erika, “Who was the small, young guy that got out and forced the horses to move on?”

She said she saw no one. A few days later, Erika and her father said they had asked around, and no one else saw the stranger.

Thanks, Pony Bob Haslam, if that was you, for lending a hand to a couple of old riders still carrying on the tradition.