Nevada’s Lost City

Nevada’s Lost City

New Images of America book uses vintage photographs to tell the Ancestral Puebloans’ story.

BY DENA M. SEDAR | SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012

Following are excerpts from the recently released publication, Nevada’s Lost City.

Nevada’s Lost City is both scientific and romantic. Buried beneath the sands of the Mojave Desert was information that archaeologists used to define the western-most settlement of the Ancestral Puebloans. Many people think that the Ancestral Puebloans were only found in the Four Corners region, but the Lost City is archaeological proof that they lived and thrived in Southern Nevada [as well].

The excavations, led by Mark Harrington, starting in 1924, have helped to redefine the Ancestral Puebloan culture and offer people a better understanding of how this culture lived.

The Lost City is also romantic—at least that is what the people of the 1920s and 1930s thought. They were intrigued by a city that had been forgotten and left to deteriorate in the desert.—from Introduction

Exploring the Lost City

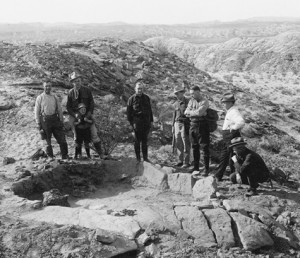

The explorations of the Lost City began in 1924 when John and Fay Perkins, two brothers from Overton, reported the presence of artifacts and ruins scattered along the banks of the Muddy River in Moapa Valley to Governor James Scrugham. In 1924, the governor sent a delegation to investigate the ruins [that included] Mark Harrington of the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. Harrington immediately recognized the ruins as Puebloan and related to archaeological sites found throughout the Four Corners region. It was a significant archaeological discovery, and excavations began in November 1924 to uncover Nevada’s Lost City.

During the 1924-26 field seasons, Harrington and his crew excavated the Lost City sites. The work was concentrated in an area east of the Muddy River that stretched about six miles north of the confluence of the Muddy and Virgin Rivers. Harrington termed this area “Pueblo Grande de Nevada,” but when the media of the 1920s, which loved to sensationalize, heard about the archaeological investigations in Nevada, they dubbed the sites the “Lost City.” The Lost City became world famous, and as a way to capitalize on that fame, a Lost City Pageant was held [May 22-23, 1925] to share the story of the area with visitors.—from Chapter One

The Salt Cave

The exploration of the Lost City was not limited to the excavation of ruins; it also included the investigation of prehistoric salt mines. The Ancestral Puebloans mined salt from caves and were able to use the salt not only for food preparation, but as a trade item as well. One of the salt caves was first noted in 1827 by explorer Jedediah Smith in a letter to William Clark (of the Lewis and Clark expedition), who was then the superintendent of Indian Affairs for the federal government.

The exploration of the Lost City was not limited to the excavation of ruins; it also included the investigation of prehistoric salt mines. The Ancestral Puebloans mined salt from caves and were able to use the salt not only for food preparation, but as a trade item as well. One of the salt caves was first noted in 1827 by explorer Jedediah Smith in a letter to William Clark (of the Lewis and Clark expedition), who was then the superintendent of Indian Affairs for the federal government.

The cave was also noted in an 1867 Morgan Exploring Expedition report. It was these reports that led Governor Scrugham, who was once a professor of mining engineering, to believe that there could be something significant in the Mojave Desert of Southern Nevada.

The salt caves were originally excavated during the 1925-26 field season by Harrington and his crew, during which they recovered pottery, stone clubs, corncobs, net bags, and yucca sandals. The archaeological explorations of the caves revealed salt-mining tools left behind by prehistoric miners.—from Chapter Two

The National Park Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Great Depression put a temporary halt to the excavations of the Lost City. There is no record of any excavations occurring in the Lost City area from 1931-33. That changed, however, in 1934, when a large-scale salvage archaeology project sponsored by the National Park Service began because the construction of Hoover Dam was going to result in the Lost City sites being covered by the newly created Lake Mead. The National Park Service’s project, [during] which the sites would be excavated as thoroughly as possible, would allow the information contained within the Lost City sites to be saved, as well as put a number of unemployed young men to work.

The National Park Service used the Civilian Conservation Corps to supply the labor. The Civilian Conservation Corps (originally known as the Emergency Conservation Work) was created in 1933 to address two primary concerns by putting unemployed men to work while working on important conservation-related projects in forests, rangelands, and parks.

Two CCC companies worked on the Lost City project. Company 974, stationed in Overton, worked on road construction, archaeological excavations, and soil erosion–prevention projects. Company 573 was responsible for the construction of the museum that would house the artifacts excavated during the project. After Company 573 was moved to Boulder City, a small company of 50 men were left behind under the supervision of Fay Perkins to continue excavation of the Lost City and complete other small projects.—from Chapter Three

The Lost City Museum

The Lost City Museum was built in 1935 by the Civilian Conservation Corps on an archaeological site now known as the Museum Site. It was built to house the collections being excavated by the CCC. The Lost City Museum was not the original name; it was actually called the Boulder Dam Park Museum. It was originally named for Boulder Dam, [now Hoover Dam].The Lost City Museum was originally built and run by the National Park Service. In 1952, the National Park Service wanted to turn over operation of the museum to the State of Nevada, and in 1953, the Lost City Museum became a state-run museum. It was appropriate that the first curator appointed by the state was Fay Perkins, one of the men who originally reported the Lost City to [Governor Scrugham]. Perkins ran the museum until health reasons forced his retirement in 1956. His position was taken over by his son, Richard “Chick” Perkins, who was the curator of the museum until 1980.

The Lost City Museum was built in 1935 by the Civilian Conservation Corps on an archaeological site now known as the Museum Site. It was built to house the collections being excavated by the CCC. The Lost City Museum was not the original name; it was actually called the Boulder Dam Park Museum. It was originally named for Boulder Dam, [now Hoover Dam].The Lost City Museum was originally built and run by the National Park Service. In 1952, the National Park Service wanted to turn over operation of the museum to the State of Nevada, and in 1953, the Lost City Museum became a state-run museum. It was appropriate that the first curator appointed by the state was Fay Perkins, one of the men who originally reported the Lost City to [Governor Scrugham]. Perkins ran the museum until health reasons forced his retirement in 1956. His position was taken over by his son, Richard “Chick” Perkins, who was the curator of the museum until 1980.

The Lost City Museum has grown since it was built in 1935 with the addition of two wings, one of which is named in honor of Fay Perkins. The museum was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 because of the Pueblo Revival architecture style and its construction by the Civilian Conservation Corps.—from Chapter Four.

What’s in a Name?

The people of the Lost City are known by several names. The most familiar term is Anasazi, but archaeologists are moving away from using this term out of respect to Native Americans. The modern Pueblo people of Arizona and New Mexico are believed to be the descendants of the people who lived in the Four Corners region and Southern Nevada.

Anasazi is a Navajo word that translates to “ancient ones” or “ancient enemies,” and the Pueblo people object to the use of this term for their ancestors. The Hopi, one of the modern Pueblo tribes, prefer the term Hisatsinom. Archaeologists and scholars have begun to use the term Ancestral Puebloan, which is the term used in the book, Nevada’s Lost City.—from Introduction

Click here to subscribe to Nevada magazine.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Lost City Museum

PO Box 807, Overton, NV 89040

museums.nevadaculture.org

702-397-2193

Hours: Thurs.-Sun., 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m.

ORDER YOUR COPY

ORDER YOUR COPY

For 20 percent off and free shipping, visit arcadiapublishing.com, and enterNVMAG2 at checkout. Offer ends October 31, 2012. A portion of the profits from the sale of the book benefits the Lost City Museum.