The Mormon’s Nevada Gold Mines—Success or Failure?

February – April 2022

A risky mining venture fails but leaves its mark on state’s history.

BY DAVE MCCORMICK

In 1890, two Mormon surveyors—Orson Smith and Jeremiah Langford—arrived home in Utah with news that might save the church from ruin. They had just finished a preliminary survey for a proposed railroad from Utah to southern California when the pair noticed mining operations 40 miles west of the projected railway. After meeting with members of the Mormon First Presidency, they advised Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint (LDS) President Wilford Woodruff that if the church acquired mining properties, it could soon clear $10,000 a month—around $300,000 today.

It wasn’t a hard sell. During the 1890s, the church was in the throes of significant financial struggles. Notwithstanding a recession that gripped the nation, the church was also undergoing property and asset seizure by the federal government. The church desperately needed to find a new venture to offset its financial losses and readily agreed to the Nevada mines. The Sterling Mining and Milling Company was formed.

The company’s first big find was unearthed when prospector George Montgomery in January 1891 discovered a quartz-vein dotted with nuggets of gold. Montgomery called this first rich strike the Chispa. This claim was within the newly formed Montgomery mining district—today located just north of Pahrump—and by April 1891, upwards of a hundred people were setting up diggings in the area.

Over the next four years, the LDS Church would continue investing in these Nevada mines: Boss, Bay, Dick, Mollie Vaughn, Blue Hawk, Blaze, Lube, Magpie, and two-thirds of the Grey Eagle mine. The Johnnie Mine was one of the company’s most exciting prospects and attracted significant outside investment.

MONEY AND OTHER TROUBLES

Although the recorded value of the company stock was set at $1 million, the amount of working capital was much less; in fact, Orson Smith informed President Woodruff in December of 1894, that an infusion of $5,000 was needed to keep the venture solvent. On the strength of Smith’s affirmation that “when the [Sterling] mill got to running it would help us pay our debts,” Woodruff accessed a loan the following day from a Salt Lake City bank.

Fiscal problems aside, the Sterling Company faced more pressing matters by the summer of 1895. Tensions flared at the Chispa mine when former mine boss Angus McArthur staked his own claim to the property. He—incorrectly—asserted that Sterling executives were lax in following the rules of Common Mining Laws and hired a number of well-armed ruffians to assist in his claim. Phil Foote, who was on the run from the law, and Jack Longstreet, a known gunfighter, were among the gang and, with unholstered revolvers, turned away miners reporting for work. When Orson Smith arrived on the scene, he was told that if he pressed the matter, he would be shot. After the county sheriff stated he could offer no remedy, Smith and McGregor rode to McArthur’ ranch in Pahrump Valley to talk sense into him, but to no avail. Trouble was brewing.

George and Bob Montgomery, holding part ownership in a number of mines, held no patience with McArthur’s interlopers and hired their own gunslingers. As the Chispa-property gunmen were sitting down to breakfast, Montgomery’s gunslingers opened up on them. Jack Longstreet raised a white flag in surrender, although many newspapers played up the gun battle, touting several killed and wounded. When the smoke cleared, the only person hit was Phil Foote, who died the following day from his wound.

LOSING FAITH

With the threat of violence behind them, gold production once again resumed at the Sterling mining properties. However, the Johnnie Mine, on which most investors fixed their chances, was turning out far less gold than expected. Now, rather than the mines alleviating LDS finances, church funds were being redirected to cover the continuing expenses of Sterling Mining Company.

Why did the LDS Church find gold extraction so difficult: was it as simple as poor claims and unruly employees? In truth, one of the biggest barriers to success was that Mormons simply did not possess the experience, machinery, or logistics necessary to extract gold at an industrial scale.

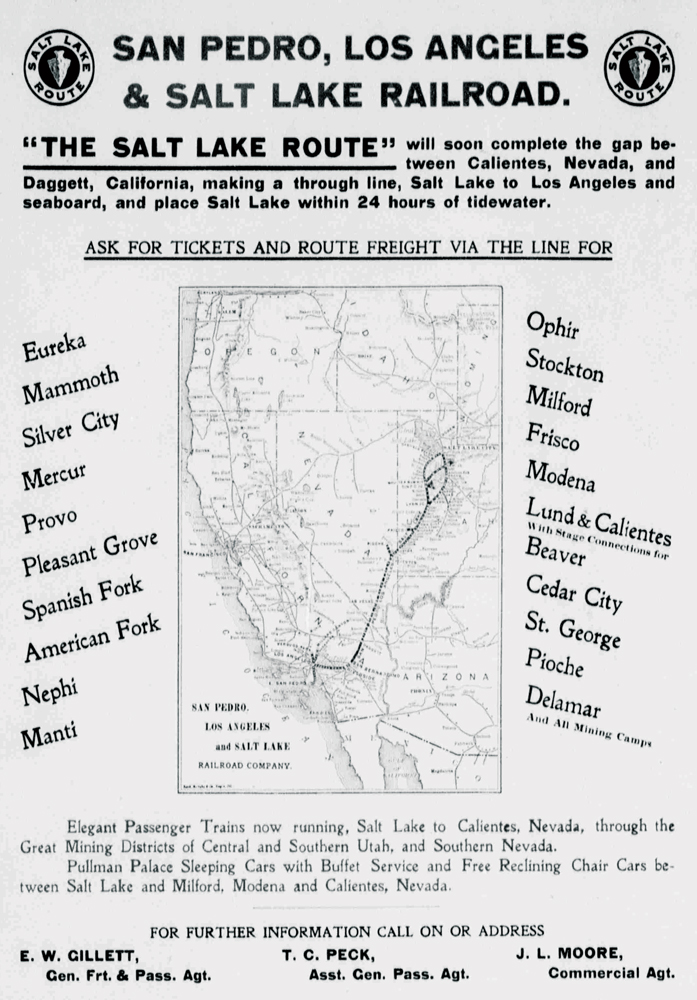

Abraham Cannon, the new mine manager, professed optimism for the flailing project. The proposed Salt Lake and Los Angeles Railroad, once in operation, would allow ore to be shipped to refineries capable of extracting gold. Cannon told everyone that the new railway was finally going make the Montgomery Mining District valuable.

Things were certainly looking up until Abraham Cannon died suddenly at 37 years old. His demise sounded the death knell for the Salt Lake and Los Angeles Railroad. This left President Woodruff to resolve that “our affairs are in a desperate condition in a temporal point of view.”

By 1897, Sterling mining efforts almost came to a standstill. An outside mining engineer reported that an infusion of $37,000 would assure a $700,000 return. This was great news but was followed shortly by the unsolved shooting death of mining superintendent Thomas Gillespie. This last dark incident had draped a pall over an operation mired in setbacks and disappointment.

The LDS leaders decided to close the book on their Nevada mining interests. In just slightly more than seven years, the LDS Church had lost $200,000.