Historic Fourth Ward School Museum

July – August 2019

Virginia City landmark has many lessons yet to teach.

BY MEGG MUELLER

“It’s not just a building full of old school desks.”

Lara Mather is ready to make her point. As executive director of the Historic Fourth Ward School Museum in Virginia City, her excitement about sharing what is really inside the 143-year-old building that sits at the south end of town is palpable.

She fell in love with the building during a tour, eventually becoming curator, and since 2016, the head of the class. The school and its contents are in amazing condition she notes, especially considering they were abandoned for almost 50 years after it closed in 1936, but her job could easily be completely consumed by the restoration efforts needed to maintain this historic property.

VIRGINIA CITY’S CROWN JEWEL

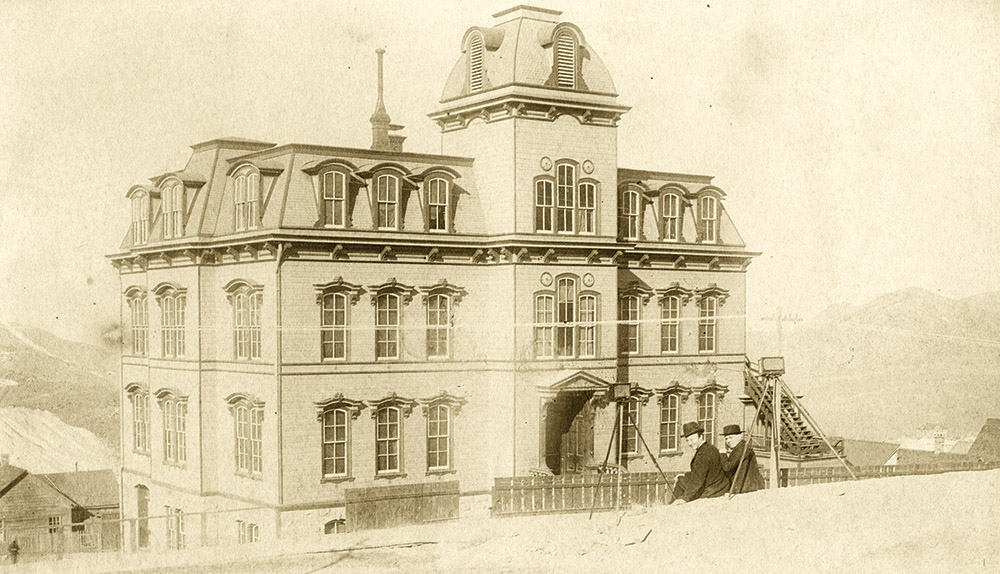

The Fourth Ward School—a four-story, Victorian Era, Second Empire-architectural style, wood school building—was built in 1876 and is the only one of its kind remaining in the U.S. The city was in a construction boom owing to the fact much of it had been destroyed by fire in October the year before.

A new school was needed to alleviate overcrowding, and when the Globe Hotel burned down, the school board bought the lot. Construction began on July 31, 1876, took just four months to complete, and cost $54,000. It was built to house up to 1,000 students.

A bustling city with international attention, Virginia City was not only Nevada’s largest community at that time, it was one of the most educated with four public schools and several private and religious schools.

In 1878, the school graduated its first two students—Anna Herrnleben and Mary O’Farrell. Not only were they the school’s first graduates, they were also Nevada’s first students to successfully complete nine grades. By 1909, the school taught all 12 grades.

By the 1930s, the town’s population had drastically diminished and barely 200 students remained. In June 1936, the last class graduated from the Fourth Ward School.

LIKE PAINTING THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE

The enormous building sat empty for almost 50 years. Time and the elements saw its glory fade, but a restoration movement began in the late 1960s. The structure was stabilized and a new future was born. The museum opened in 1986.

There is always work to be done; the floors are almost entirely original, and there’s always an area that needs to be cleaned and oiled. The wooden desks need to be oiled regularly, and there is always—always—painting to be done, both inside and out. The challenges of restoring such a building—it’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places—are tenfold, Lara explains.

“The entire exterior of the building needs to be stripped, restored, and repainted. There are nails popping out everywhere,” she says. “We did get a $106,000 grant from the Commission for Cultural Centers and Historic Preservation that will restore the south and west sections of the Mansard roof.”

“That was substantial, but I have extensive restoration that needs to be done on the building. It’s just under 25,000 square-feet,” she says, trailing off, before continuing, “I need a lot of money.”

Along with the financial challenges, the logistical concerns when restoring a historic building are equally great. Lara explains that any restoration has to follow the Secretary of Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties.

“We can only replace a piece that is beyond use, and then it has to be a ‘like’ piece,” she explains. “Safety trumps historic requirements, however, and we were able to install roof anchors for our workmen doing exterior maintenance.”

One notable change to the original 1876 structure is the tower on the north side of the building. The original tower was pulling away from the building and beyond restoration, so it was rebuilt. Today, it includes an elevator, making the building and tours available to those with limited mobility. Few historic buildings are accessible due to the restoration restrictions.

Knowing what needs to and can be replaced is one thing, but the next step is finding workers qualified to work on the property. Nevada is already seeing a crunch in its labor force due to rapid growth, but the pool of companies qualified to work on historic buildings is extremely small. Reyman Brothers Construction from Sparks does most of the work on the Fourth Ward School, along with many other historic buildings. According to Lara, they are one of the few companies that do historic work, and they are incredibly busy.

“Luckily for us, they have a vested interest in the building,” Lara says. “It’s hard to get them because they are so busy, but they have done a lot of the work, and they know what to do.”

DELVING DEEPER INSIDE

Maintaining and restoring the building are only one focus the museum has right now, however. Educating the public as to what lies inside the beautiful facade is the other. Along with the incredible architecture of the four-story building, the interior reveals how innovative the design was for the times. A story in the “Territorial Enterprise” in 1876 noted, “…A fertile cause of sickness among school children is the old style of open-vault privies. The new building will be supplied on every floor with water closets through which water will run constantly.”

Along with modern facilities, the building was wired for electric light soon after it opened. The original gas lights were kept, but electric wires were run through the pipes to the fixtures. One feature of the building was quickly adjusted, however, to accommodate the mores of the time. To access the girl’s bathroom, the young ladies were required to go through a classroom to a door leading to the balcony, then down the balcony to the facilities. At that time, Lara says, it was not proper for little boys to think of little girls and the bathroom in the same thought, so a wall was constructed in the classroom, creating a corridor the girls could use to access the balcony, thereby remaining unseen. Today, that corridor houses an exhibit that depicts the perils of falling into a mine shaft, complete with a young male ghost.

Along with that very popular feature, the school now houses a unique look at the history of The Comstock. Without fanfare or kitsch, the Fourth Ward School Museum reveals an intimate look at life in Virginia City during its heyday and beyond.

“We have an amazing archival collection—6,000 photos, thousands of artifacts,” Lara says. “We really want to get the word out that we have this collection. It’s mostly Comstock history, but we also have quite a bit from San Francisco, too.”

The archival collection is available by appointment to anyone wanting to research The Comstock and Virginia City, but it’s also an incredible tool for people looking into their family trees.

“We have a lot of genealogy information and family history, also,” Lara explains. “There were so many people who came here to make their fortunes, and while not all were successful or stayed very long, we have information on a lot. There are people around the world who have a connection to Virginia City.”

Along with archival material, Fourth Ward School has a number of exhibits for visitors to view as they wander three of the building’s floors. The history and culture of The Comstock Lode is on full display, as are the school’s student body in an amazing homage to the alumni. Some notable names were students of the Fourth Ward School, and the photos and details of the children are fascinating. There is, naturally, an exhibit on mining in The Comstock, with plans for an even bigger one in the near future, and a changing gallery.

While it’s not just, as Lara says, a building with school desks, one of the classrooms is available to tour and yes, there are 143-year-old wooden school desks, along with other original items.

The museum is open from May to October, with three floors open for self-guided viewing. However, tours are available by appointment all year long, and offer an even closer glimpse at the depth and breadth of history the Fourth Ward School Museum has to offer.