A Blast at News Nob

March – April 2017

(This story originally ran in our March/April 1996 issue)

Covering an atomic test for Nevada Magazine was an assignment like no other.

BY ADRIAN ATWATER

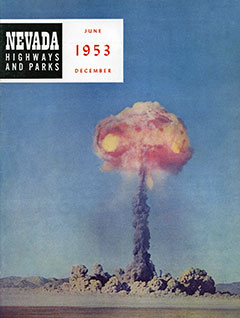

It went by several names: “Operation Doom Town,” “Observation Shot,” and the official Title, “Upshot-Knothole.” Whatever the name of that 1953 atomic test, it made a bang-up impression on Fred Greulich and me.

Fred was the pioneer of Nevada Magazine, then called Nevada Highways and Parks, and he served as editor, writer, and copy boy of the highway department’s publication. I was the department’s lone photographer in those days, and one of my duties was to travel with Fred around the state.

One day Fred said he had read that an atomic blast was scheduled for the Nevada Proving Ground, and VIPs, service brass, and news people could attend it. In two years of A-bomb testing there had been about 20 other aboveground blasts with minimal press coverage, but this detonation would receive major publicity. The test would take place on March 17, 1953.

Fred very much wanted to be included in this invite, and so did I. We got approval from Governor Charles Russell, who had already been invited. The government issued us credentials following background and security checks. A few days before the test Fred and I found ourselves driving to Las Vegas with camera gear and film, pad and pencil, and lots of enthusiasm.

Would it be safe? Today we know about the dangers of radiation, but they weren’t public knowledge then. The question of safety never entered our minds. If governors and other VIPs had been invited, we figured it had to be safe.

Day One: We went to the old Las Vegas City Hall, where along with 600 other guests we registered and received information packets, ID badges, film badges, and viewing goggles.

Day Two: We boarded buses for a preshot visit to the test site. During the 65-mile ride, there was much good-natured wisecracking among the news people, many of whom were well-known journalists. I remember talking with the popular commentator John Cameron Swayze, who sat across the aisle. Movie photographers were there to film the event for newsreels. Fred and I felt privileged to be a part of this fraternity.

After we reached Mercury, the test site’s headquarters, officials gave us a tour of Yucca Flat, where the blast would take place the next day. A mini-community had been built on the flat for scientific study. Two houses had been erected, and cars, military equipment, and power-line poles were scattered in the desert.

Day Three: Somewhat bleary-eyed, Fred and I arrived at City Hall at the appointed hour—just after midnight. Instead of carefree chatter, there was a lot of grumbling on the bus from those newsmen who had taken advantage of the Las Vegas continental nightlife. Fortunately, Fred and I had got in a few hours of sleep, but a number of our colleagues hadn’t been to bed yet. Once we were on the road, sawing wood could be heard throughout the bus.

At News Nob, our observation point for the blast, the army had set up an outdoor mess hall under floodlights, and we were treated to a good breakfast with lots of hot coffee. Photographers began scrambling up the nob, stumbling over rocks in the near-dark and being ever mindful of rattlesnakes. Soon a forest of tripods was in place. The VIPs and brass took their seats on benches below.

About 5 a.m. the countdown began over the P.A. All cameras were aimed at a little light bulb glowing on the tower at point zero. We put our goggles on, and at the count of zero, there was a complete white-out.

As soon as the white-out subsided, we took off our goggles and saw a ball of deep red fire on the desert floor. The boiling fireball rose on its mushroom stem, and the desert churned with dirt. Thunder echoed off the mountains. The P.A. advised us to watch out for the shock wave. Across the desert, a roll of dirt was approaching like an ocean wave. Its arrival proved quite a jolt, and I reached for my tripod out of concern that it might topple over.

The mushroom cloud continued to rise to20,000 or 30,000 feet, and although it was still quite dark below, the sun tinted the upper part bright orange. A white cap formed on top of this mass; officials said it was an ice cap that resulted from the moisture entering the freezing-cold atmosphere.

For the first time, army troops were engaged in such an operation.GIs in full battle gear had crouched in trenches much closer to ground zero than we were. Soon a fleet of helicopters brought the troops to an area where the media could interview them. Most of the Gls said it was pretty scary, but a few insisted it wasn’t big a deal. I noticed they were still pretty wide-eyed and, as we used to say, “nervous in the service.”

Later we climbed onto the buses for a tour of the aftermath. Army personnel had gone ahead with Geiger counters to monitor the radiation levels. We could see right off that the tower at ground zero and the closest house were no more—nothing remained.

We were allowed to get off the bus a quarter mile from the second house, but first, we had to put on protective booties that slipped over our shoes and up to our knees. Officials told us that if we dropped anything, it would be retrieved and decontaminated. The house was still highly radioactive, and the side facing the blast was charred black. We were told that it had been in flames, but the shock wave had extinguished the fire.

Cars and equipment close to the blast were burned-out, twisted hulks. The sparse grass, sage, and greasewood were charred black. I noticed a lizard scurrying around and noted to Fred that I‘d bet on that creature being pretty radioactive. A whirlwind (dust devil) approached us from the hot zone. It enveloped us and went on its way. I wondered at the time how many harmful particles were deposited on us in its passing.

Soon we were back on the bus, after depositing our booties. On the way to Las Vegas, we stopped at the Indian Springs airbase and were allowed to roam at will. Among the aircraft, there was a giant B-36 bomber, designed to fly long distances and deposit atom bombs during the Cold War. It became known as the plane that never dropped a bomb in anger. Off to one side was a jet fighter that had flown through the mushroom cloud that morning for scientific purposes. It was being decontaminated by several servicemen hosing it down with a solution.

Years later I received correspondence from government officials stating that their records showed I had been an observer of a nuclear device and may have received radiation. I was assigned a number and given a toll-free phone number for Bethesda Naval Hospital if I should develop any problems. I have had numerous skin cancer operations on my face, neck, and ears over the years, but I don’t know if any of it is due to the blast. Presumably, my skin problems are due to years of sun exposure and lack of sunscreen. The radiation film badge that was issued to me was never collected, so I kept it as a souvenir.

But we were more weary than worried that evening when we arrived back at City Hall. Fred and I were literally bombed out and tired of the pace and crowds. Next morning found us driving south to do a story on Davis Dam. It was good to be in the peaceful desert again and a place where we felt at home.

Adrian Atwater lived in Carson City. He donated his goggles, film badge, and ID badge to the Nevada State Museum for use in a historical exhibit about the bomb. Adrian died in 1998.