The Great Train Robbery

March – April 2018

HIGHWAYMEN

Nevada outlaws conducted the first train robbery in the West.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

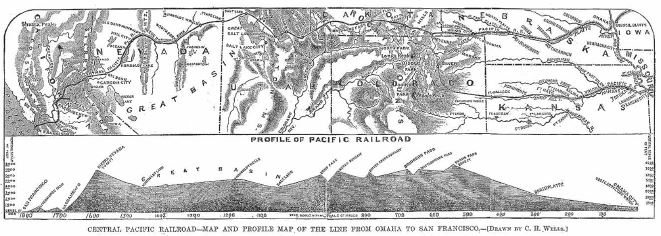

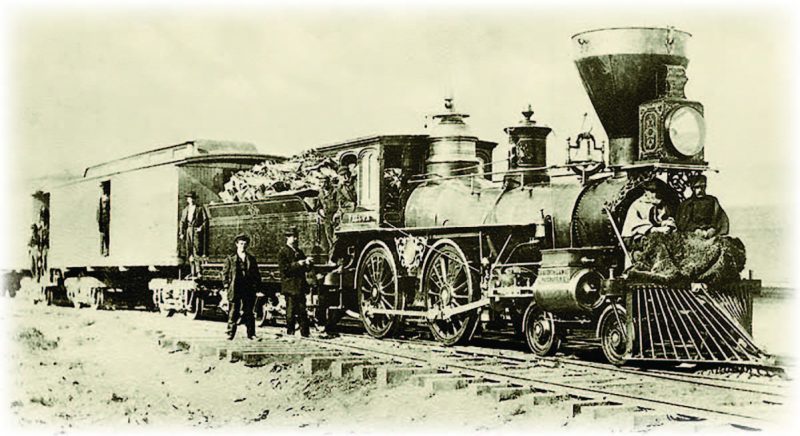

Just two and a half short years after the Central Pacific Railroad arrived in Reno, an engineer found his forehead on the business end of at least one six-shooter. Rather inconveniently for the engineer, the man whose trembling finger danced on the trigger had a glimmer of gold in his eyes and wasn’t in the mood for digging it from the ground. The fairly immediate threat of lead passing through his body must have come as a surprise to the engineer, considering that during the time leading up to this moment, the line had operated unscathed, and had acted as a major artery bringing lifeblood and commerce to the burgeoning West.

Just two and a half short years after the Central Pacific Railroad arrived in Reno, an engineer found his forehead on the business end of at least one six-shooter. Rather inconveniently for the engineer, the man whose trembling finger danced on the trigger had a glimmer of gold in his eyes and wasn’t in the mood for digging it from the ground. The fairly immediate threat of lead passing through his body must have come as a surprise to the engineer, considering that during the time leading up to this moment, the line had operated unscathed, and had acted as a major artery bringing lifeblood and commerce to the burgeoning West.

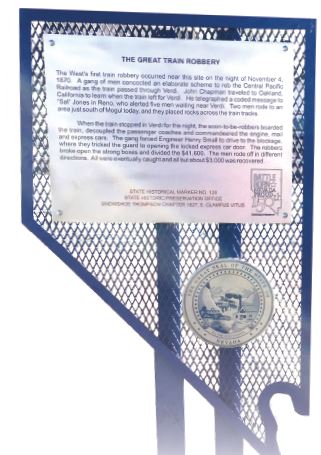

But the source of life was not without leaches. Shortly after supplies, wealth, and success began sailing across the Sierra, this seemingly ordinary train was interrupted by a group of diabolical defectors with dastardly designs who saw an opportunity to feast, sinking their fangs into the success of the West. And deep they sunk around midnight on the frosty Nov. 4, 1870 near Verdi, when some $41,600 in gold was pinched during the first—but certainly not the last—train robbery of the old West.

ROAD AGENTS

When the Reno-bound engine slowed at the small station in Verdi (then Hunter’s Crossing), the gang that boarded didn’t immediately brandish the pistols from their jackets and begin the stickup; that happened several minutes later. They also didn’t immediately hold the engineer, Henry S. Small, at gunpoint and force him to trick the Wells Fargo guard, Frank Marshall, to simply open the door to the loot; that also happened later. What happened at that moment in history in Verdi is that Sunday school teacher, livery owner, and notorious Comstock capital-ist and hustler “Smiling” Jack Davis—along with his band of thieves—calmly boarded the eastbound train.

Where exactly the train was when pistols were drawn and demands were made isn’t known, but most believe the heist happened just six miles west of Reno. As former State Archivist and Nevada Historian Guy Rocha detailed in his August 2000 article titled “The Verdi Train Robbery Didn’t Happen in Verdi,” “Quietly boarding the train around midnight in Verdi, the robbers hijacked the engine and express car just east of town, setting the rest of the train adrift.”

It is at that place the loose engine and express car encountered the bandits’ barricade of boulders and rail ties on the tracks, and the train screeched to a halt; It’s there that tens of thousands of dollars in gold coins were shoved into boots and sacks for the getaway; And it’s there that a group of highwaymen rode off in the night in separate directions with almost more riches than they could hold, without a single shot fired.

CRIMINAL COHORT

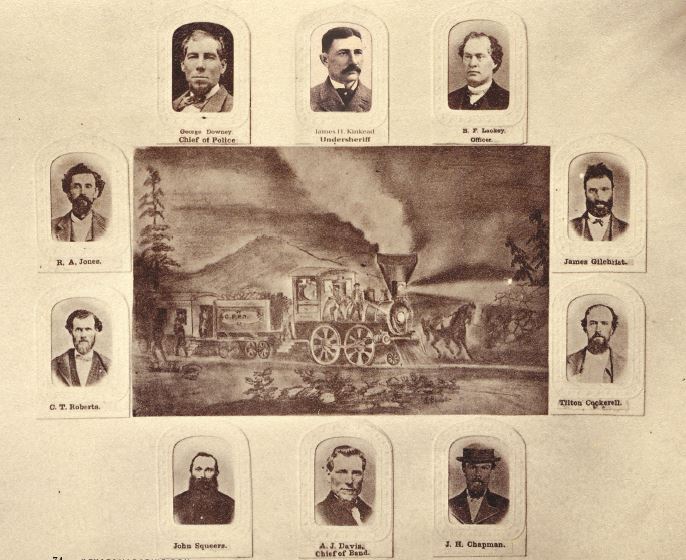

The unit’s ringleader, Davis, would later admit that he couldn’t figure out why a robbery such as his hadn’t been attempted sooner. He would come to find out that it may have been because the Wells Fargo guards prided themselves on their deadly abilities to defend their payloads since the days of stagecoach robberies began. Their motto, “By God and by Wells Fargo,” showed they meant business, but the gang of curmudgeonly road agents assembled by Davis were sworn to solemn loyalty and were prepared to square up with the toughest of lawmen.

Davis’ first three assembled men went by the names of Tilton Cockerell, John Squires, and E.N. Parsons, and were all men he knew from shady stage robberies in the past. Another rider named Sol Jones was recommended by a friend to join the team, as was James Gilchrist—a poor miner with the least experience of the bunch.

A man named J.H. Chapman was also an accomplice to the crime. While the group of outlaws laid in wait for the train they would eventually rob, Chapman delivered a coded letter alerting them to the gold. Chapman learned that the Central Pacific’s train No. 1, the “Overland Express,” was carrying the payroll for workers of the Yellow Jacket Mine in Gold Hill from Oakland to Reno. Once he confirmed the rumor, he telegrammed a message to Sol Jones that read, “S. Jones. Send me sixty dollars, if possible and oblige, Joseph Enrique.” It’s believed that the “sixty” meant either the treasure was only guarded by six men, or that the treasure was worth $60,000. Regardless, the telegram told Davis and his men it was time to strike.

ONE BY ONE

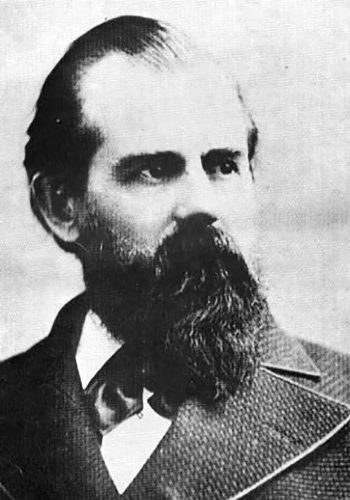

Not a single drop of blood was shed as the bandits rode away in the night, and the red-faced lawmen and politicians wasted no time pursuing justice. Bounties included $10,000 from Wells Fargo, $20,000 from Nevada Governor Henry G. Blasdel, and $500 from the U.S. Post Office thrown in for good measure. Though many sought the outlaws, it would be Washoe County Undersheriff James H. Kinkead who would put on the toughest chase. History maintains that Kinkead rode out to the robbery site the day after it occurred to search for clues. The search lead his attention to a boot print in the snow Governor Henry G. Blasdel much smaller than others—made from the kind of boot that gamblers typically wore. Kinkead knew that no railroad man would wear a boot of this fashion, and that it must have belonged to one of the bandits, so he followed the tracks all the way to a hotel in Sardine Valley, California, some 10 miles west of Verdi.

Though the robbers had split in all different directions after the heist, eventually Parsons, Squires, and Gilchrist reconvened, and found themselves in the same Sardine Valley hotel. Parsons and Squires, being the more experienced of the trio, woke early and left at daybreak, leaving the inexperienced Gilchrist to awaken to the sound of Undersheriff Kinkead questioning the innkeeper about the robbery. It was then only a matter of time before Gilchrist made a run for it, but was quickly apprehended by Kinkead and led to a Truckee, California, jail.

Once Gilchrist was captured, he sang like a canary and began selling the others out. Kinkead nabbed Parsons at a Loyalton, California, hotel, and he also bagged Squires while he hid out at his brother’s ranch. Cockerell was arrested by a different lawman in a saloon north of Reno, as was Sol Jones, who was taken from the home of a gambling buddy. Even the messenger Chapman was arrested as he headed to a saloon for a celebratory drink.

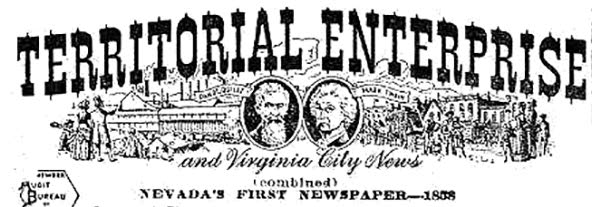

Justice would come to hit ringleader Davis like double-aught buckshot. Instead of hiding out like the others had done, “Smiling” Jack Davis showed himself all around The Comstock, hoping to show he had nothing to hide. The day would come, however, when a deputy would place a still gloating Davis under arrest, and bring him in front of Virginia City Chief of Police George Downey. Davis further maintained his innocence, even when Downey made a bet with Davis that he had captured one of Davis’ robbers. When Davis asked where the captured robber was, the police chief simply pointed directly at Davis. An article in the “Territorial Enterprise” would claim that on that day, “Davis’ smile, which was generally brilliantly white, turned blue.”

LOST AND FOUND

Though Gilchrist and several of the accomplices less involved walked free because of their testimonies, the others were not so lucky, and would be spending years in the Nevada State Prison. Davis got 10, Chapman got 18, Parsons and Squires each got 20, and the least lucky of the bunch, Cockerell, got 22. Every great train-robbery story includes a prison break, and this one is certainly no exception. About a year after sentencing, Cockerell, Chapman, Parsons, and Squires brawled bloodily during a riot at the prison, eventually escaping and taking off into the hills, once again racing for freedom. For most, their stint was even less successful than the last, and they were rounded up quickly. Parsons, though, managed to remain free for five years before being recaptured. Davis, meanwhile, sat back and watched the break happen, not getting involved. He was released after serving three years of his sentence for good behavior.

Though Gilchrist and several of the accomplices less involved walked free because of their testimonies, the others were not so lucky, and would be spending years in the Nevada State Prison. Davis got 10, Chapman got 18, Parsons and Squires each got 20, and the least lucky of the bunch, Cockerell, got 22. Every great train-robbery story includes a prison break, and this one is certainly no exception. About a year after sentencing, Cockerell, Chapman, Parsons, and Squires brawled bloodily during a riot at the prison, eventually escaping and taking off into the hills, once again racing for freedom. For most, their stint was even less successful than the last, and they were rounded up quickly. Parsons, though, managed to remain free for five years before being recaptured. Davis, meanwhile, sat back and watched the break happen, not getting involved. He was released after serving three years of his sentence for good behavior.

Then by either bad luck or revenge, he was killed two years after his release, shot in the back by none other than a Wells Fargo guard carrying a shipment of gold.

It’s rumored that while most of the gold from the robbery was recovered, Davis stashed away $3,000 before his initial capture, and the secret of its location died. Many searched the hills of Six Mile Canyon and banks of the Truckee River after his death, though the gold has never been recovered.

If you decide to pursue the lost gold and end up finding it, plan on laying low and heed the lessons learned by the desperados: don’t hide out in a saloon or a hotel. These establishments are notorious for getting outlaws nabbed. And surely if “Smiling” Jack Davis were alive today, he’d tell you to watch your back, for frontier justice always finds those who deserve it.

On Nov. 5, 1870, the “Territorial Enterprise” printed the following: “The Great Robbery,—All the talk upon the streets to-day is of the great robbery on the railroad, between Reno and Verdi, last night. It is believed here that the robbers got in the vicinity of $150,000. Chief Downey, Sheriff Cummins, Officer Lackey and other officers and detectives left this city early this forenoon for the scene of the robbery. Wells, Fargo & Co. offer $10,000 reward for the recovery of the treasure, or any part of it, and the arrest and conviction of the robbers. Under the head of telographic will be founding an account of the robbery, as sent us from Reno. It is probably correct, though it differs much from the stories told on the streets. We are informed that near a hundred men are out in pursuit of the robbers.”

History maintains that after the initial Great Train Robbery, the same train was robbed once more on the same day. Nevada Historian Howard Hickson detailed the event in his 2002 article titled, “Robbed Twice on the Same Day.” “The second heist was just 20 hours later, 380 miles to the east. It was the same train on the same run on the same day, but, by then, train holdups were suddenly very common,” he wrote. “It seemed impossible, but the same train had the bad luck of later being boarded by several robbers who looted the mail car of registered letters and packages.”