Fort Churchill

November – December 2013

Fort Churchill

State Historic Park offers a glimpse into Nevada’s pre-statehood past.

BY GREG MCFARLANE

Almost everything about life in mid-1800s Nevada seems difficult to fathom and even more difficult to have endured. We no longer worry about hostile natives, high infant mortality, and taking weeks to cross the desert on horse-drawn wagons, but at one time such ordeals were commonplace. That onerous era is on permanent display at Fort Churchill State Historic Park, a living commemoration of many of the people and events that helped forge this resilient state.

Every Nevadan who passed high school civics knows that the state was admitted to the Union during the throes of the Civil War (our motto, “Battle Born,” provides a clue). But The War Between the States wasn’t the only—or the earliest—conflict to have played a vital part in Nevada’s formation. A year before the infamous shots were fired at Fort Sumter, The Paiute War was in full swing at Pyramid Lake and the surrounding region. That struggle, and its aftermath, led to the founding of one of the state’s most fascinating historical sites, located east of Carson City.

EARLY HISTORY

In 1861, with violence between Indians and settlers at its peak, and blood having long been shed on both sides, the United States Army commissioned Fort Churchill so that an influx of new settlers from the East could live in some semblance of peace. The fort housed as many as 300 soldiers, providing a bulwark against Paiute forces. The Army selected for its base a site on the northern banks of the Carson River, a well-traveled area that had come to the attention of explorers a few years earlier.

In 1861, with violence between Indians and settlers at its peak, and blood having long been shed on both sides, the United States Army commissioned Fort Churchill so that an influx of new settlers from the East could live in some semblance of peace. The fort housed as many as 300 soldiers, providing a bulwark against Paiute forces. The Army selected for its base a site on the northern banks of the Carson River, a well-traveled area that had come to the attention of explorers a few years earlier.

In the midst of a lifetime full of superlatives and pioneering feats, Colonel John C. Fremont was the first explorer to pay a visit to what is now Fort Churchill. Traveling with legendary frontiersman Kit Carson, Fremont mapped the region in 1843. By the end of the decade, the area was overrun with fortune seekers heading west to lay their claim to California gold. It’s estimated that more than 150,000 speculators passed through.

In the midst of a lifetime full of superlatives and pioneering feats, Colonel John C. Fremont was the first explorer to pay a visit to what is now Fort Churchill. Traveling with legendary frontiersman Kit Carson, Fremont mapped the region in 1843. By the end of the decade, the area was overrun with fortune seekers heading west to lay their claim to California gold. It’s estimated that more than 150,000 speculators passed through.

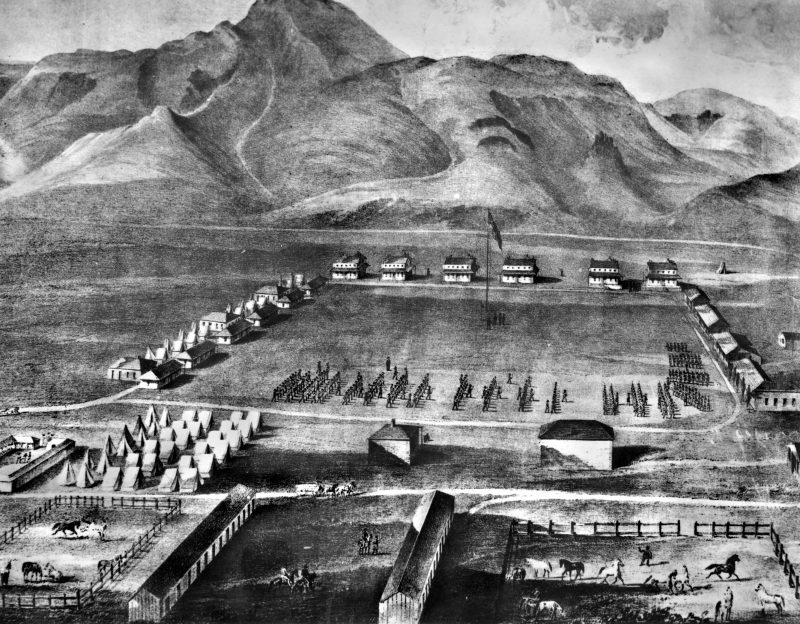

Directly past the park’s entrance are the adobe ruins of the fort itself—once a functioning and modern military outpost. Its main compound included six officers’ quarters, an armory, and multiple barracks. There are also the vestiges of a quartermaster’s operation and, tucked discreetly in at the back, the laundresses’ building. As park ranger and historian Mike Dinauer explains it, on a compound populated with lonely young men thousands of miles from home, some of the more enterprising laundresses were rumored to offer services that had little to do with the cleaning of garments.

The Paiute War was bloody but brief, its outcome a decisive victory for the United States. With Indians no longer posing a serious threat, Fort Churchill was decommissioned in 1869. The federal government wanted to hand the complex over to a young and burgeoning state, but a lack of funds forced the Nevada legislature to politely decline. (In fact, it wasn’t until 1957 that the Nevada Legislature authorized the purchase of the entire property and made Fort Churchill part of the Nevada Division of State Parks.)

THIS LAND IS BUCKLAND’S

With the state initially refusing to take on the responsibilities of stewarding Fort Churchill, it became time to solicit offers from private interests. A plucky young Ohio transplant named Samuel Buckland made the successful bid, paying $750 for close to eight square miles of stark but strategically situated land. It would turn out to be one of the best real estate deals in Nevada history.

With the state initially refusing to take on the responsibilities of stewarding Fort Churchill, it became time to solicit offers from private interests. A plucky young Ohio transplant named Samuel Buckland made the successful bid, paying $750 for close to eight square miles of stark but strategically situated land. It would turn out to be one of the best real estate deals in Nevada history.

Buckland was a rancher, innkeeper, and the 19th-century equivalent of a tollbooth operator, the latter two occupations working in tandem to make him affluent. He operated the sole bridge that would transport passengers over the Carson River, which today trickles through the park with just enough flow to hydrate the cottonwoods on its banks.

If a traveling party was too late for the last crossing of the day, they were

welcomed to patronize Buckland’s other venture—the nearby boarding house that also served as a neighborhood gathering place and Pony Express station. Ever the resourceful entrepreneur, Buckland used materials from the vacated fort buildings to construct his boarding house.

Buckland died in 1884. W.J. Marsh bought the estate for $50,000, meaning that a modest investment grew to 67 times its original size under Buckland’s care.

Buckland Station sits across the highway from the rest of Fort Churchill, the two-story ranch house a beautifully maintained reminder of a hardier era. Inside are displays of everyday frontier life, along with a small theater that shows a 12-minute film about the station’s history.

SAVING THE FORT

While Buckland Station prospered, Fort Churchill itself stayed untended, teetering on the verge of literal collapse. Years of neglect turned into decades, as the Earth reclaimed the withering clay structures for itself. By the Great Depression, local members of the Daughters of the Ameri- can Revolution had had enough. They began laying plans for preserving this important chapter of Nevada’s history. These determined women convinced the federal government to transfer the fort buildings, or what was left of them, to state control. Then, the Civilian Conservation Corps got to work not only staving off the pending ruination of the fort, but erecting several other buildings on the property that are still in use.

While Buckland Station prospered, Fort Churchill itself stayed untended, teetering on the verge of literal collapse. Years of neglect turned into decades, as the Earth reclaimed the withering clay structures for itself. By the Great Depression, local members of the Daughters of the Ameri- can Revolution had had enough. They began laying plans for preserving this important chapter of Nevada’s history. These determined women convinced the federal government to transfer the fort buildings, or what was left of them, to state control. Then, the Civilian Conservation Corps got to work not only staving off the pending ruination of the fort, but erecting several other buildings on the property that are still in use.

In 1994, the state bought the Carson River Ranches, five square miles of riparian plots southeast of the main entrance, and transferred them to the park. Visitors use the ranches primarily for camping, horseback riding, and fishing (smallmouth bass and carp being the most abundant species). The following year Buckland Station was annexed, and the park took on the boundaries that it currently holds.

An unassuming hill overlooks the park’s administrative offices, and atop that hill sits a solemn remembrance of the harshness of existence back in territorial days and nascent statehood. The fenced and gated cemetery once marked the final resting place of 46 Union soldiers who had served at Fort Churchill. In the 1880s, 44 of their bodies were exhumed (as for the remaining two, it’s possible that they were never buried there in the first place).

The bodies were removed to Lone Mountain Cemetery, eight blocks from the state Capitol in Carson City. The depopulated Fort Churchill cemetery continues to sit largely empty, its only occupants being Samuel Buckland, his wife Eliza, and their children.

TODAY AT FORT CHURCHILL

These days, park supervisor Scott Egy oversees a staff of six, including three part-timers. Together they keep the park clean and functioning for visitors and the occasional dignitary. Last summer, Governor Brian Sandoval enjoyed lunch in The Orchard, a pastoral day-use area that abuts a lightly traveled section of Alternate U.S. Highway 95. Sandoval was one of an estimated 20,000 guests the park saw that year, the majority of them stopping by in the spring and fall.

There are several day-use areas throughout the park, along with dozens of campsites. Given Fort Churchill’s remoteness and quietude, the park does attract its share of characters. One group of 15 or so “mountain men” takes over a campground every spring, sleeping in tepees and carrying black-powder muskets and tomahawks to complete the picture.

The tranquility at Fort Churchill is sporadically interrupted by the rush and hue of a freight train, coursing a track which has bisected the fort since its founding. The valuable right-of-way once belonged to the Carson & Colorado Railway, a narrow-gauge line that transported ore from Inyo County, California. Should you see a train at Fort Churchill now, it’ll be standard-gauge Union Pacific rolling stock, the C&CR having ceased operations in the 1960s.

Those who cannot document the past are condemned to forget it, thus Fort Churchill keeps many of its artifacts displayed for posterity’s sake. Open daily, the Col. Charles McDermit Visitor Center contains maps, ordnance, army supplies, and even full-scale replicas of the same Union troops who brought peace to the land a century and a half ago.

Those who cannot document the past are condemned to forget it, thus Fort Churchill keeps many of its artifacts displayed for posterity’s sake. Open daily, the Col. Charles McDermit Visitor Center contains maps, ordnance, army supplies, and even full-scale replicas of the same Union troops who brought peace to the land a century and a half ago.

Fort Churchill’s resident coyotes seem to outnumber the overnight human guests. The park is one of the most peaceful locales in the state—an irony, given the fort’s origins—and is easily accessible. Even at its busiest, Fort Churchill offers plenty of opportunity for solitude and serenity.