Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 6

November – December 2016

ODYSSEY OF A GHOST TOWN EXPLORER

LAST OF SIX-PART SERIES EXAMINES ABANDONED SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTHERN NEVADA.

PART 6: MILES

BY ERIC CACHINERO

5,724 miles. That is the driving distance from Los Angeles to New York City and back again, with about 150 miles to spare. It’s also the distance I have driven within the past year, entirely within the state of Nevada, searching for ghost towns.

The total seems tremendous when I look at it as a whole, but tiny when I aim the microscope at each mile. Each mile was special. Many miles greeted me as a friend, some shunned me. Some miles were plagued with deep muck, others were graced with sunshine. Some miles flirted passionately with steep cliffs, others hummed the blues across spacious plains. Miles laughed at me with their dead ends and disappointment. Miles led me home. Miles searched my soul.

Last issue, I wrote about how Metropolis perished dehydrated and diseased, starved of the precious water that once gave the town life. This issue, I’m on the opposite side of the state, visiting remains of a settlement that had a problem decidedly opposite in nature. If a town located in one of the driest climates in the U.S. being entirely submerged in trillions of gallons of water isn’t ironic, then I don’t know what is.

BUST

Southern Nevada generally receives more traffic than other parts of the state. It is for this reason that many ghost towns have either been destroyed or are located on private property. However, several protected historic sites and living ghost towns still dot the map.

I’m tackling each mile solo this trip, and the realization hits me pretty tough as I begin driving to find Potosi—located just outside Las Vegas. I catch myself thinking about how I’m careening into the great wide open by myself in 100+ degree temperatures, something we advise people not to do. I should really start following my own advice.

Mormon settlers discovered a “mountain of lead” in Potosi in 1856, and word quickly spread. The mines were worked briefly before becoming abandoned due to the lead’s undesirably high zinc content. Productivity waxed and waned over the years, and during World War I, the site was used as an important source of zinc.

Unfortunately for me, Potosi is a bust. Much of the area is now privately owned, and if there are still ruins on public land, I cannot find them. Although the town misses the mark, it is still a beautiful drive, nonetheless.

THE GOOD

I set my sights on Goodsprings—a living ghost town that is home to one of the oldest saloons in the state. For the first time during my travels, a paved road leads all the way up to the townsite. Something about being in Goodsprings just feels right. The town’s penchant for history coupled with its inviting atmosphere has me quickly perched atop a rickety barstool in the Pioneer Saloon scanning the articles and relics that adorn the walls.

Prospectors found silver-lead ore in the area in 1868. A mining district followed, but was soon abandoned because the lead did not contain enough silver to satiate the lust for riches. Prospector and cattlemen Joseph Good remained in the area after others had given up hope, and subsequently the local springs were named after him. By 1886, prospectors seeing value in the lead formed the permanent settlement of Goodsprings, and discovery of the Keystone gold mine came with it. By 1893, about 200 people called Goodsprings home, and by 1906, the mines produced nearly $600,000 in gold, predominantly.

Because the land contained a swath of desirable metals and minerals (gold, silver, lead, and zinc), production boomed during 1915-18. Wartime skyrocketed demand, and Goodsprings matched the supply. Nearly 85 million pounds of zinc was mined, which has many practical uses including making brass. Along with production, the population rose to around 800, followed by stores, a school, first-class hotel, and hospital.

Today, a highlight of the town is Pioneer Saloon, which celebrated its centennial in 2013. Prominent businessman George Fayle built the saloon and branded it a social hub, and it continues to remain so. Bullet holes in the wall complete with a coroner’s report tell how a card cheat met his demise here during the joint’s rowdier years. The saloon is also the location where actor Clark Gable is said to have languished for three days while he awaited news that his wife, Carole Lombard, had tragically perished in a plane crash near Mt. Potosi.

After partaking in the local custom (a beer), I poke around Goodsprings, admiring some of the old structures. I eventually aim in the direction of Eldorado Canyon, and enjoy the air conditioning on the way there.

THE BAD

It’s 107 degrees outside when I reach Eldorado Canyon, and growing up in the northern Nevada climate has me ill-prepared for the heat. Still I manage to explore the canyon, marveling in the psychedelic colors and offerings.

It’s 107 degrees outside when I reach Eldorado Canyon, and growing up in the northern Nevada climate has me ill-prepared for the heat. Still I manage to explore the canyon, marveling in the psychedelic colors and offerings.

The Spanish were the first non-natives to descend upon Eldorado Canyon during their 1700s conquest for gold, but deemed the area unproductive. It wouldn’t be until the mid-1800s that the worth and wealth of the canyon would be truly discovered, creating one of the richest mining districts in pre-Nevada. The mine was named Techatticup, derived from two Paiute words meaning “hungry” and “bread,” as many Paiutes in the surrounding barren hills are reported to have frequented the mining camps begging for food.

The district was very remote in those days, and with its remoteness came murder and vigilantism. It is said that in the 1870s, the nearest sheriff lived in Pioche (more than 200 miles away), so not even murder was a crime heinous enough to warrant a visit from the law.

Eldorado Canyon became a haven for Civil War deserters, and attracted all types of outlaws. It was here that two of Nevada’s most notorious renegade Indians—named Ahvote and Queho—claimed victims. Queho is said to have claimed the lives of more than 20 victims, while Ahvote only murdered a modest five.

The Techatticup Mine is open to this day, though only for tours.

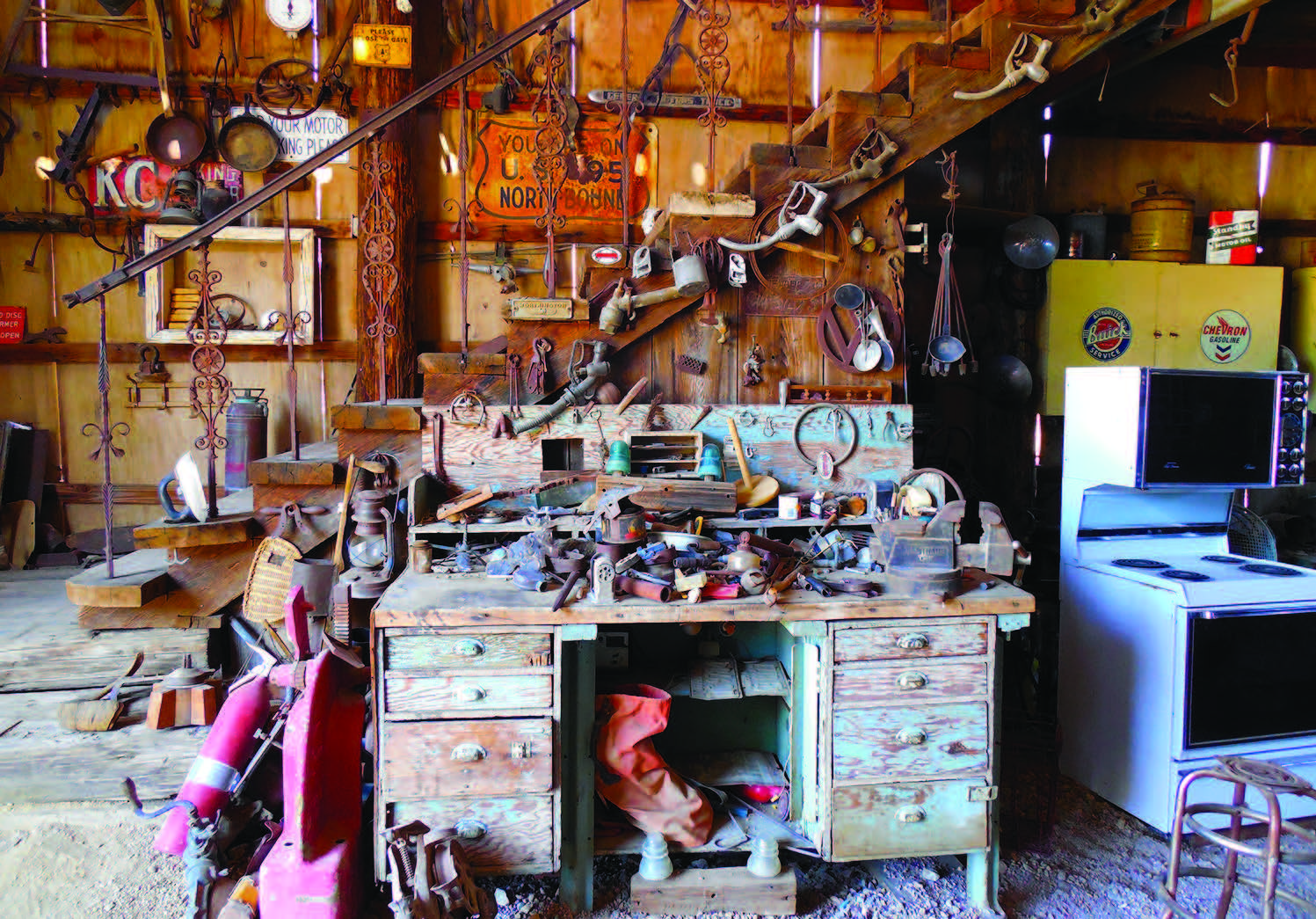

Tony and Bobbie Werly—who purchased the mining claims, a store, stamp mill, bunkhouse, and miner cabins in 1994—own 50 acres of Eldorado Canyon. The couple has been restoring the property, which is now a popular tourist destination.

Some of the canyon’s popularity comes from its appearance in several movies and television shows, including the 2001 crime film “3,000 Miles to Graceland.” Movie props can still be found in the town.

I spend some time exploring and taking photos, though the heat is really kicking in. It’s not long before I tap out and take the hour-long drive back to Las Vegas.

THE CALAMITOUS

The next day, I make an attempt to get to St. Thomas as early as possible, as I plan on hiking and want to be sure I’m being smart about the temperature. Alas, taking detours in Las Vegas, repeatedly pulling over to take pictures in Lake Mead National Recreation Area, and just general lollygagging put me there smack dab in the heat of the day, with each of the 104 degrees taunting me. The hike to St. Thomas is only 2.5-miles round-trip, but even a short hike in that kind of heat can get dangerous very quickly.

And, once again, I ignore my own advice and go trudging to the ghost town, snapping as many photos as I can before I find myself too drenched in sweat to continue.

St. Thomas was founded shortly after Brigham Young commenced settlement of the Muddy (now Moapa) Valley in 1864. By April 1865, more than 600 acres of land had been platted near the townsite with the intent to grow cotton, and just three years later, the town was nearing 600 in population. Settlers originally believed St. Thomas was located in Utah; however, an 1870s land survey shifted the boundary by one-degree longitude, and St. Thomas officially became part of Nevada. The Nevada government ordered the settlers to pay back taxes, leading to near-abandonment of the town in 1871. However, by 1880, new settlers gave life to St. Thomas once again, and the population hovered steadily around several hundred for many years.

In the early 1930s, St. Thomas had a problem. The town that had enjoyed mostly peace and quiet for decades now faced a slow-motion deluge—the approaching water from the recently completed Boulder (Hoover) Dam. Residents began intermittent evacuation, and in 1934, the government began preparations to move the cemetery. By 1937, the water was 12 miles from the town, and crops were still being grown, but by 1938, St. Thomas would drown. Bureau of Reclamation engineers estimated the town would become submerged on June 18, 1938.

Some residents held out until the very end. The last, Hugh Lord, stayed until the water allowed him to climb from his door onto his boat, set his house on fire, and watch it burn. Though the engineers’ guesses came close, “Taps” officially played for St. Thomas on June 11, 1938—the day the post office closed. Journalist Jori Provas described the town’s death eloquently: “St. Thomas did not die. It was murdered. Not maliciously, but definitely with aforethought. St. Thomas was surrendered, given up, sacrificed, if you will, for the good of many.”

As I’m cooking my insides walking around St. Thomas’ concrete-foundation remains, seashells crunch under my feet. Because of severe droughts, the town’s remnants have reemerged at least nine times since it first held its breath. The town’s story is reminiscent to a Greek Tragedy. It’s ironic that a town that drowned once again pops its head up and there’s no water anywhere in sight. I get the photos I need, then make the trek back to my vehicle, and head toward home.

LAW OF PERIODICAL REPETITION

The very first words I wrote in this series were, “Ghost towns are skeletons of history.” One year later, I still find this to be true. They don’t tell the entire story, but reveal clues as to what life meant to the people who called them home. Ghost towns are a humble reminder that life is fragile, and that maybe in 1,000 years, people will write of our lives, picking clues from the remains of the towns and cities we now call home. They’ll write of hardships and of luck. They’ll close their eyes and imagine what life was like back then.

I end this series with the always-capable words of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, who humbly reminds us that nothing is permanent.

“Will this wonderful civilization of to-day perish? Yes, everything perishes. Will it rise and exist again? It will—for nothing can happen that will not happen again. And again, and still again, forever. It took more than eight centuries to prepare this civilization—then it suddenly began to grow, and in less than a century it is becoming a bewildering marvel. In time, it will pass away and be forgotten.

Ages will elapse, then it will come again; and not incomplete, but complete; not an invention nor discovery nor any smallest detail of it missing. Again it will pass away, and after ages will rise and dazzle the world again as it dazzles it now—perfect in all its parts once more. It is the Law of Periodical Repetition.” — Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain), “Mark Twain’s Fables of Man”