Stewart Indian School

November – December 2016

Lessons to be Learned

Stewart Indian School is Still Teaching that the Past Should be Remembered

Stewart Indian School is Still Teaching that the Past Should be Remembered

BY JOYCE HOLLISTER

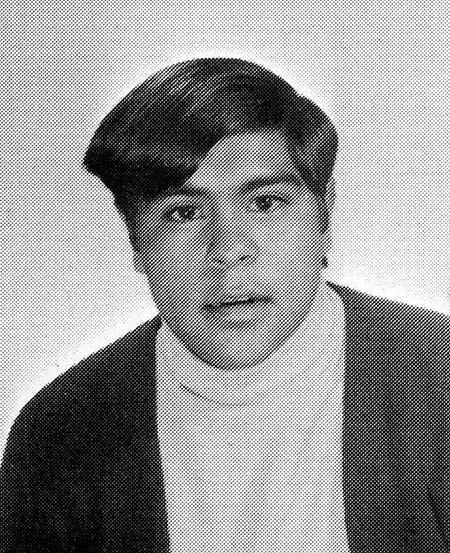

Sports and girls. Those were what made Buck Sampson happy at Stewart Indian School in Carson City during his first few weeks there in 1968.

While he ended up playing baseball and joining the boxing team—not to mention meeting his first wife, Lula, at Stewart— Buck acknowledges it took him some time to adjust to life at the boarding school.

“But after you see all these Indians from different tribes and different states, you had a lot of friends from all over,” he says.

His favorite subject was American Indian history, partly because he liked to argue with the teacher that the history textbooks were wrong.

“I would say ‘no, no, it didn’t happen that way.’ My grandpa— and he learned it from his dad—said it didn’t happen like that out here.”

Buck stood his ground, despite having been sent to the office. After a while, the other students backed him up, he relates with glee.

Today, his memories of his time at the school are mostly positive. While he isn’t the only one to feel that way, other students had very different experiences during their time at Stewart.

A CONTROVERSIAL EDUCATION

Stewart’s origins were with the military, patterned after the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Indian boarding schools were part of an assimilation program designed to make Indians more “American.”

It’s no surprise that many early students were unhappy at Stewart. Children were taken from their homes—some as young as 4 years old—and confined to the school all year. The children were not allowed to speak their native languages or participate in their traditions and ceremonies.

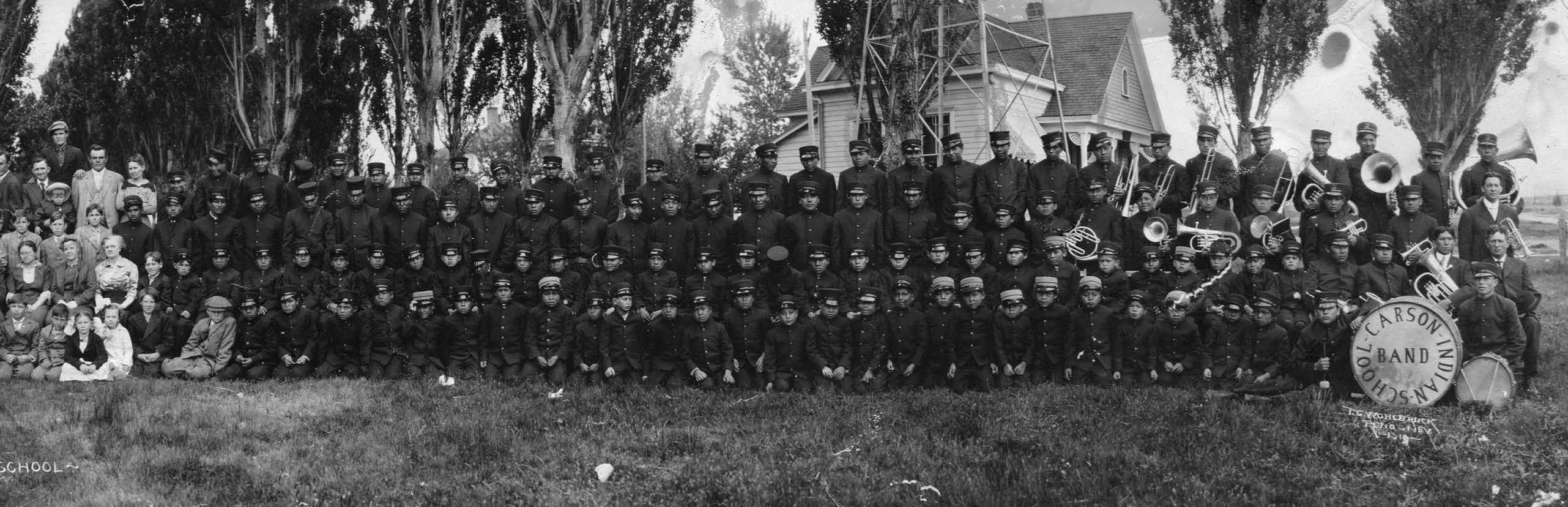

The children had to wear uniforms and march to their classes—vocational training for boys and home arts for girls. About 30,000 students attended the Stewart Indian School from 1890 to 1980, and as Sherry Rupert, executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission says, there are 30,000 personal stories—positive and negative—to tell.

“They didn’t have the opportunity to have their parents around them or their families, which is so important in our culture,” Sherry says.

Matrons made sure the students were doing their daily chores and going to school, but there was nobody to nurture them.

“To me,” Sherry says, “some of the most detrimental effects of these schools is that loss of the ability to nurture. If you don’t have that nurturing around you, then how do you teach your children and grandchildren?”

The climate at Stewart changed as the years went by. Flogging was outlawed in the 1920s. In the 1930s the “Indian New Deal” reform extended to Stewart with Alida Cynthia Bowler, the first female superintendent. She encouraged native languages, arts and crafts, and traditional dancing until the end of her tenure in 1939. In the 1940s, the Wa-Pai-Shone Trading Post sold Indian-made items. Academics, rather than vocational training, became the focus in the 1960s.

Today, Stewart is one of the few Indian school campuses still intact and open to the public. Many alumni remember the school fondly and return each year to meet friends at the Father’s Day Powwow.

PRESERVING THE FUTURE

“People ask me why would I want to preserve a place that had such terrible beginnings?” Sherry says. “My inspiration is that many of my family members went to this school and their stories need to be told as well as others who were part of the whole boarding school era.”

Sherry wants to place Stewart’s history into the context of how boarding schools shaped generations of American Indians. At the same time, she is often amazed by the affection the general populace has for the school.

“Governor Brian Sandoval, Congressman Mark Amodei, and Carson City Mayor Bob Crowell played basketball out here as young adults and remember their connection,” she says.

So much so that they pledged support for the Nevada Indian Commission’s Stewart Indian School Living Legacy Project fund-raising campaign at an event last May. The 2015 Legislature designated the commission as the coordinating agency for the campus and awarded funds for developing its master plan.

Their goal? To obtain funding for a new cultural center in the 1920s-era stone administration building. Visitors will learn how the school was established to educate Great Basin tribes: Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone. Later, other tribes such as the Hopi and Navajo sent students, and eventually, 200 tribes were represented. To facilitate the requests for former student information and photos, the center will have computers for visitors to use for research. Indian artisans will sell their work, Stewart memorabilia will be displayed in the museum area, and souvenirs sold.

Sherry envisions packages where visitors can spend the night in a dorm, eat at the dining hall, and see a film in the auditorium. A new welcome and information center will have campus guides for visitors and distribute the brochure for the Stewart Indian School Trail, a self-guided cellphone walking tour that was instituted in 2007 (see sidebar).

What sets Stewart apart from other Indian boarding schools is the 110-acre campus itself. The original wood school buildings were replaced between 1919 and 1934 when superintendent Frederick Snyder brought Hopi stonemasons to build and teach students how to construct native stone cottages, dorms, and classrooms in the National Park Service “rustic” style. Tall trees and concrete walkways invite visitors for a stroll.

“I look at what we have here, the beauty of the unique buildings that we have to share with the world, really, and the potential for this school,” Sherry says. “We’re trying to breathe life back into this campus and bring it to a place that people want to come and experience—and bring the respect for this place back to what it should be.”

A Family’s History

Buck Sampson’s connection to Stewart goes back two generations. His grandfather, Dewey Sampson, and Dewey’s older brother, Harry, attended the school in the early 20th century. Harry was kidnapped from the Mound House area and taken to Stewart. No one knew where he had gone. His family searched fruitlessly for two weeks, but Dewey had heard of students being taken to Stewart. He told his parents he was going to the school to search for his brother.

“When he got here, he got captured. They cut his long hair and dressed him up,” Buck relates. “I asked him one time, ‘did you like it here?’ At first he said he didn’t care for it, but he decided he would stay and learn English because the world was changing.”

Dewey graduated in 1918. He taught music as an adult and with Harry cofounded the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, where Buck—a member of the Tasiget band of Paiutes—lived as a child. Dewey was elected in 1938 to the Nevada Assembly. He is the only full-blooded Paiute ever to serve in the Legislature and he sponsored legislation to create equal opportunities for Nevada Indians.

Buck’s grandmother, Maude, attended Stewart as did several others in his family. Buck’s mom, a Shoshone, does not like to talk about her years at the school. She and her brothers were orphaned in Tonopah in 1943. They were aged 10, 8, 6, and 4 when they were taken by buckboard to Stewart. The two youngest ran away—twice. The siblings joined the Catholic Church just so they could be together on Sundays.

As for Buck, at the suggestion of his father, Floyd Sampson—a Stewart alum and professional boxer—he went to the gym at University of Nevada, Reno, where the boxing coach let him spar with the team while he was still a junior at Stewart.

“I took one guy on, then another guy on, and another guy and then another guy, and he was throwing all kinds of guys at me,” Buck says.

The coach invited him back the next day.

Even so, Buck was taken by surprise when he was given a boxing scholarship—as well as an English scholarship and an American Indian history scholarship—his senior year. Now retired from the City of Reno, Buck also boxed around the west. He was a youth boxing coach for two decades and is in his third term as chairman of the Nevada Indian Commission’s Stewart Advisory Committee.