Doing Business in Pioche Often Resulted in Deadly Encounters

Spring 2021

Desperados aplenty took advantage of this Wild West town, leading to commerce that came at a high price.

BY DAVID MCCORMICK

Sometime during the peak of Pioche’s boom, Athe Meeks, returning from delivering a load of timbers to a mine, was suddenly startled by two men with weapons drawn. The pair rushed out in front and forced Meeks’ mules to a stop. The highwaymen ordered him to show his hands, but he would have none of it; instead he pulled his six-shooter and shot Al Miller, one of the would-be robbers, dead. The second desperado, known as Little Frank, fired a wild shot at Meeks. He returned the favor, and his shot hit its target—Little Frank was found a little way down the road, also dead. Although most times it was the banditti who came out on top, this was just one of the scenarios that played out between robbers, cattle rustlers and horse thieves, and those delivering their goods to customers in Pioche.

BOOMTOWN

BOOMTOWN

Many of the peddlers carrying their ware to Pioche were Mormons from Utah. Newly formed Nevada had financial wealth from gold and silver holdings, but lacked for almost everything else. Utah had an abundance of produce, meat products, and a sundry of other items needed in nearby Pioche, so what could be better?

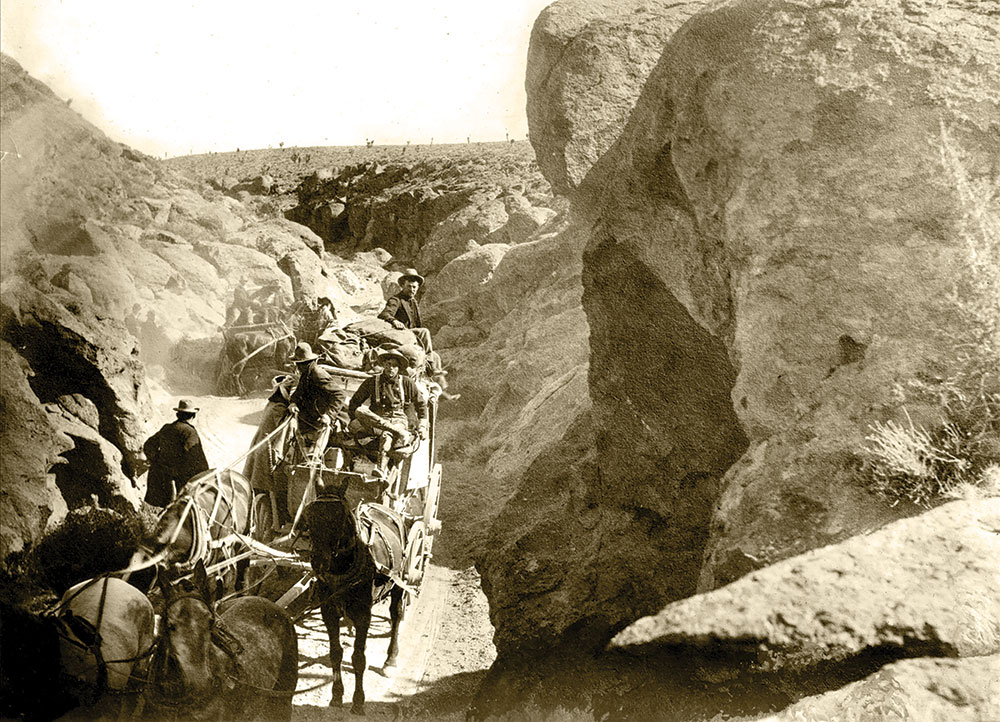

However, no matter how promising this idyllic financial position appeared, the Mormon peddlers from Utah crossed into Nevada en route to Pioche under threat of being waylaid by brigands. The freighters and coach drivers were often unaware of thieves concealed among a clump of trees, until they jumped out with guns in hand. But those who made it through the gauntlet to Pioche found success. Pioche had the most ravenous appetite for goods of all the Nevada mining camps inside the reach of southern Utah. And as such, it drew purveyors of myriad supplies from the Utah counties of Beaver, Iron, Millard, and Washington. It was a daily spectacle of wheeled conveyances coming to town: immense freight wagons with long processions of freight animals were seen unloading goods at the various stores, and stagecoaches carrying payrolls lined the main street.

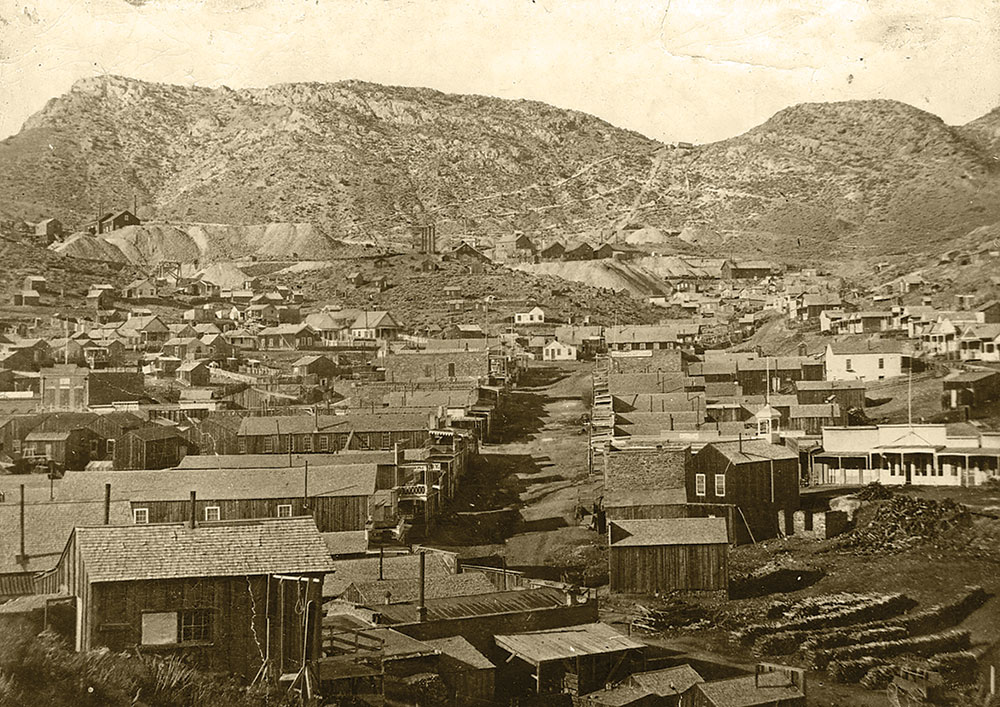

The discovery of rich deposits of silver ore in 1864 began to put a Nevada community on the map. But it wasn’t until 1870, that it became known as Pioche. It was that year that F. L. A. Pioche began mining operations in earnest—for that effort, the community was affixed with his name. By 1872, more than $5 million in ore was extracted from the Pioche mines. As with many mining communities, Pioche’s life span was short lived—by 1886, the boom ended, leaving Pioche nearly empty, a mere shadow of itself. By 1950, with the closing of the last mines, Pioche faded into partial dormancy. The town had began with a small population of 250 residents, but when the news of huge silver deposits harkened, Pioche soon swelled to at least 6,000 souls. Many undesirables—claim jumpers, card sharps, and soiled doves—flooded the area. Their main forte was to separate miners from their money.

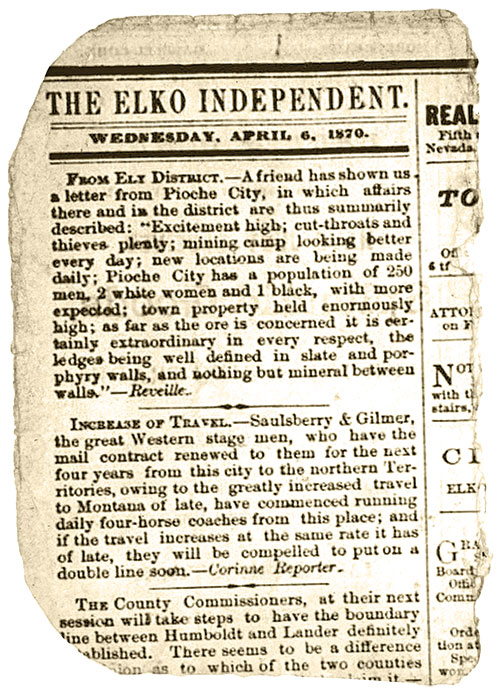

With residents such as these, Pioche earned its reputation as the “most lawless camp in the old west—rivaling even Tombstone in Arizona.” An article in the April 6, 1870 “Elko Independent” tells the tale of Pioche. “Excitement High; cut-throats and thieves plenty.”

Pioche also became the perfect place for road agents who knew when traders’ wagons were empty, their pockets full of proceeds, and they were setting off for home. The criminals were also somehow privy as to when a stagecoach was heading into town, with treasure boxes full of gold coin. One of those skulking the route was Charles A. “Jack” Harris. Harris’ specialty was robbing Wells Fargo & Company stages. The stagecoaches carried large payrolls of hard currency with which to pay employees of the mines and other businesses. Harris had his repertoire down to a science; he would come out of the shadows without warning and ambush a stage en route to Pioche. After ordering the stage to stop, he sent them on their way unharmed, minus the payroll. It was all so smooth a transfer he rarely needed a gun. Armed with the highwayman’s description, the Wells Fargo station agent was sure the culprit was Harris. Recognizing they could not catch him in the act, Wells Fargo came up with the solution to deter these robberies. Offer Harris a payment, paid weekly—the stipulation being he be present at the Wells Fargo Office as each stage arrived. Those payments would be cheaper than losing the contents of each strongbox hijacked. Harris agreed—he appeared at the office just before the stage rolled into town. But the robberies still continued. Harris had discovered a short cut back to Pioche after he held up the stage.

HIGHWAYMEN

Unfortunately, not all hold-ups concluded on such a humorous note—and Wells Fargo certainly wasn’t amused. Two traders 60 miles out from Pioche, named Pierson and Ames, were accompanied by a man known as “Pilgrim.” It’s not known how it came to be that he joined the two traders but what is known is that, somewhere along the route, he attacked the two. Pilgrim got the drop on Pierson and Ames and shot them both with their own guns. One died instantly; the other was mortally wounded. The killer then separated the two men from their valuables, and rustled one of the horses and lit out for the unknown. There was little chance that he could be caught.

Along with freight wagons, the stagecoaches provided rich targets for the highwaymen. A stagecoach traveling from Pioche to Salt Lake City, on Oct. 24, 1870, was held up by desperados brandishing weapons. They demanded the stage driver toss down the Wells Fargo strong box. They then ordered the passengers from the stage, proceeded to divest them of their valuables to the tune of $1,500, then they put their spurs to their mounts and made their getaway. The sheriff’s posse headed out after them, but with such a head start, they were most likely in the wind. This was rather disconcerting—stage robberies had become the rule rather than the exception.

Occasionally, a desperado was found guilty of robbery charges. Such was the case of one William T. “Doc” Bell. It was suspected he was behind a stagecoach robbery that occurred in 1876 just one-half mile out of Pioche—the haul was $2,000. No proof was found that he was the culprit, but he did get his comeuppance: he was convicted for his role in a mail robbery that took place in November 1877 near Cherry Creek. In another case, George Mayfield, known as a “knight of the road,” pled guilty to a string of robberies—several times, he held up stages on the route from Hamilton to Pioche. He openly admitted to robbing one stage outside of Pioche of several hundred dollars, and added the following postscript to the crime; by the time news of the robbery reached town, he was already spending the proceeds at Fred Baker’s faro game in Pioche.

NO HEIST TOO BIG OR SMALL

Large and small robberies happened on the route to and from Pioche. In 1874, bandits held up a fast freight wagon and took off with an undisclosed amount. Another robbery, on a much smaller scale, involved an elderly fruit vender. The old man had sold all his stock, pocketed $200 in proceeds, and was on his way home. Thirty miles out of Pioche, he was accosted and his money and watch taken before being pistol whipped and hog tied. He remained in that pickle until discovered the following day.

Robberies on the roads outside of town were not the only manner by which people were robbed. Within the town itself, robberies were commonplace. In January 1874, Rose Wilson was robbed just before sunrise by three men who relieved her of $3,000; she was given a severe beating to boot. She was able to identify two of her assailants as area miners.

Normally, livestock dealers fared well at Pioche as there was great demand for beef created by the hungry miners. To fill this demand, the cattlemen would drive their animals directly to the butchers in Pioche. But, their problems arose when rustlers made off with some cattle before they even departed Utah. And, it was not unheard of to lose cows along the trail, either. Some of the rustlers were brazen, driving 40 or so head along the road. One of those trading in stolen beef was Ben Tasker, who lived just inside the Utah line, at his Desert Springs ranch. There, he excavated a few narrow cellars where he hung the dressed beef. He knew without the hides the cattle could not be identified. He would haul the hind quarters and loins to Pioche to sell at 6 cents a pound. He made a good profit, having paid nothing for the cattle.

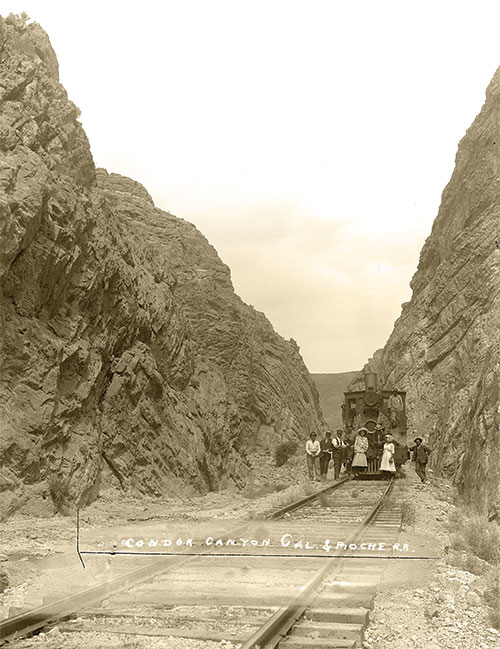

It was a dangerous world of bone chilling encounters for those supplying sorely needed goods to Pioche. The intrepid peddlers, risking their lives traveling to and from Pioche, have been replaced by truckers and railroad cars, which might not be immune to thievery, but are much less inviting targets for would-be robbers.