Sweet Saviors of Virginia City

Summer 2021

Sisters brought care and comfort to wild mining town.

BY CRAIG MACDONALD

In the 1860s, Virginia City was a rough and tumble mining camp, with 24-hour hustle and bustle. Men swarmed the streets and saloons, while miners labored deep within the tunnels underneath the town.

The loud, constant clanking metal of stamp mills and jarring explosions echoed throughout the valley and mountains. It was a dangerous place, where rope and cable sometimes broke, sending cages full of miners falling to their deaths. Many an accident or fire in the mines or city left children as orphans.

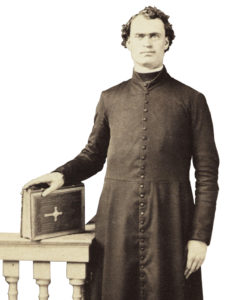

The town was in desperate need of an orphanage, school, and hospital—needs that the recently installed priest Father Patrick Manogue especially recognized, as he had been orphaned in Ireland as a very young boy, along with his six siblings.

The rugged, former California gold-miner—who was often called “Wyatt Earp with a collar” for the way he pulled husbands from taverns and ordered them to surrender their paychecks to their wives—turned to the Catholic Church’s top missionaries to help solve some of Virginia City’s most pressing needs.

SOMEONE TO CARE FOR

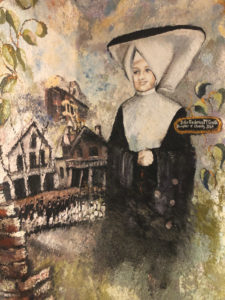

At the request of Father Manogue, the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul traveled over the Sierra Nevada Mountains from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Between 1864-97, he was able to bring more than 50 sisters to care for the town’s needy and open Nevada’s first orphanage, along with a hospital and two schools. The sisters sought to provide spiritual comfort, regardless of race, culture, or religious preference. The tireless women shared a dedicated, hardworking, compassionate, and unselfish spirit that bettered those around them and spread a caring attitude that most Nevadans share to this day.

On Oct. 8, 1864, the first three sisters arrived by stagecoach; Frederica McGrath, Elizabeth Russell, and Xavier Schauer. They provided a much-needed “breath of fresh air” in the male-dominated city. They definitely stood out in their distinctive blue habits, guimpes, and white cornettes, which caused the Paiute Indians to call them “God’s Geese.”

The proactive Sisters went throughout The Comstock—into homes, mines, businesses, and even jails in their efforts to assist anyone in need. They saved the town thousands of dollars by aiding the poor, sick, and injured.

GETTING RIGHT TO WORK

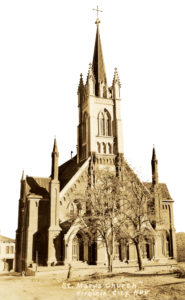

The “Virginia Daily Union” reported the school opened Oct. 17, 1864 “with 50 female children attending the first day” in the basement of the newly-opened St. Mary’s of the Mountain Church. In the first year, they aided more than 112 students and ran two schools—one for boys and one for girls.

In 1867, they opened Nevada’s first orphanage which was supported by a diverse group of local citizens, including Dr. Wake Bryarly who donated free medical care to the children.

In 1876, with the support of mining icon John Mackay and his wife, Marie Louise, the sisters opened the town’s first hospital, which had space for 70 patients, and was run by Sister Ann Sebastian. It helped save the lives of injured miners and many others.

Built on land donated by Mackay and his wife, St. Mary Louise Hospital was a four-story brick building with 36 rooms—each with hot and cold running water. Today, the structure, which was saved from being demolished by Father Paul Meinecke, Louise Curran, and local artists in the 1960s, is the renowned St. Mary’s Art Center.

The sisters, along with local housewives, were also known for their incredible vegetable and flower gardens, created out of the rough, rocky soil. They received water—free of charge—for their gardens from the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Company.

When budget-conscious accountants decided to start charging the women for the water, John Mackay came to their aid, insisting they should not have to pay. He even subsidized water from Lake Tahoe for use in the school and hospital. But as mining profits fell, new owners took over and there were further attempts to collect fees for water usage.

SUPPORT BEGINS TO DRY UP

In June 1885, the company diverted its water into huge metal tanks to prevent “borrowing.” On the evening of June 25, however, someone punched several holes in a tank which lead to the posting of water guards. Two days later, a large explosion shook the area as dynamite blew up a water flume.

Investigators were never able to discover who was responsible but the sisters were never under suspicion. They were all law-abiding “Angels of Mercy” on The Comstock.

When the notion of charging the sisters for water was brought up again, (now) Bishop Patrick Manogue came to their rescue. The Irish-born, 6-foot-3, 250-pound man who paid for his education to become a priest by goldmining in Moore’s Flat, wrote a sympathetic letter explaining how the sisters helped orphans survive and how taxpayers would have to assume such costs if the sisters free water supply ended.

An attorney also declared that the sisters had purchased land with the understanding the water would be free. The company finally withdrew its request and the sisters went about the business of their charitable works.

TIME TO FLY

By the mid-1890s, much of the mining had stopped and many people were abandoning the once-booming Comstock. When the sisters received orders they were to move on to other assignments around the country, more than 450 Virginia City residents signed a petition requesting they stay. But in 1897, the sisters closed their convent, hospital, and schools, and left town for other duties. They did, however, return to the Silver State in the 1950s to help out at St. Teresa School in Carson City.

The Sisters of Charity (also called Daughters of Charity) will be remembered for their amazing, pioneer efforts in Nevada. As one person noted: “They opened a vein of social services as rich as The Comstock Lode!”

Today, only one Sister of Charity remains in Virginia City—Sister Mary Angelica Olivas, who rests peacefully in the Catholic cemetery, now part of Silver Terrace Cemeteries. The memory of their spirit of service, however, lives on in the lives of those Nevadans who still unselfishly care for their neighbors.