The Saga of Lydia Adams-Williams

Fall 2020

Nevada native carved her way into the history books.

BY KAREN DUSTMAN

Impatient, impetuous, and occasionally infuriating, Lydia Adams-Williams was all those and more. The word shy, however, was definitely not included in that list.

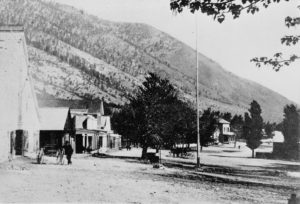

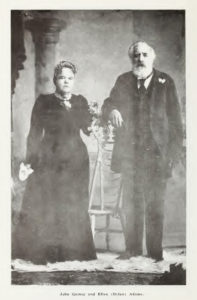

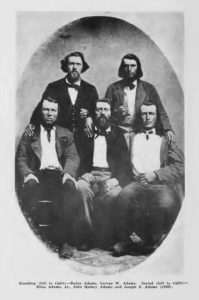

Born shortly after the Civil War (July 18, 1867), Lydia was the oldest child of Carson Valley pioneers John Quincy and Ellen Dolan Adams. The Adams Ranch where Lydia would grow up lay just a mile or so north of Mormon Station. Even back then, the ranch was historic. Lydia’s father and uncle had purchased the original acreage in about 1853, making it one of the earliest land claims in Carson Valley.

Lydia’s parents thought she’d make a fine teacher, and sent her off for training—first to the San Jose Normal School, then to Stanford University. Fresh out of college and just 22 years old, Lydia fell into the post of principal for the tiny Genoa School in April, 1890, by sheer luck, after the incumbent fell ill. And that same year, on Thanksgiving Day, Lydia married dashing newspaperman Delbert Williams in Carson City.

On the surface, it seemed like a perfect match. Williams was the prominent owner/editor of the “Genoa Courier” newspaper. Witty, beautiful, and 16 years his junior, Lydia was every bit Williams’ intellectual equal. But soon the two strong personalities began to clash, and Lydia was granted a divorce in 1898. In a sign of just how rancorous the split was, Delbert refused to pay the $10 per month the court had ordered as alimony.

Now 31 years old, Lydia was out on her own—and determined to make her own way. In 1899, she circulated the news that she’d been appointed a “corresponding secretary” by the Nevada Commission preparing an exhibit for the forthcoming Paris Exposition (World’s Fair). Sounds impressive, right?

Except, however, the title was unpaid, and hardly a unique honor. The “Daily Appeal” was forced to explain in November that the editor of “each and every newspaper in Nevada” had been similarly appointed. Lydia, in other words, had abundant company. The “Nevada State Journal” discovered an even more embarrassing bit of backstory. The title, it reported, had been conferred on Lydia “simply to get rid of her constant application.” Yup, shy definitely wasn’t part of her nature. In what probably felt like a slap in the face, Lydia’s appointment was officially rescinded in March 1900.

MOVING ON

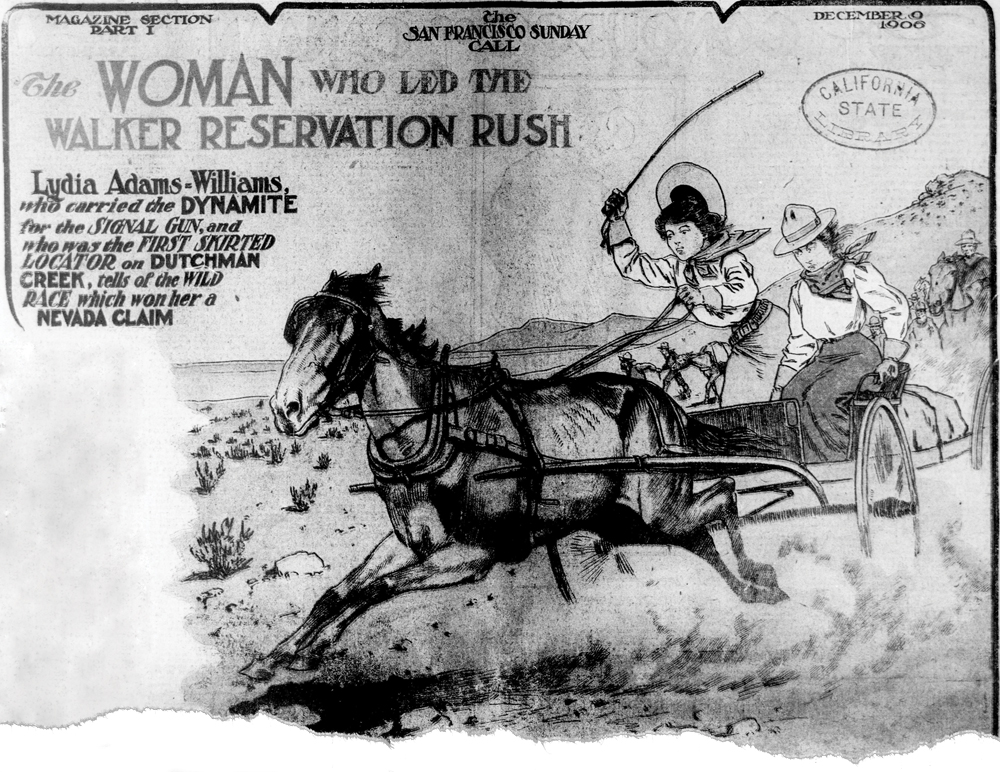

In 1904, Lydia moved east to Washington D.C. for a fresh go at teaching school. But her affection for Nevada—and her appetite for adventure—never waned. Upon learning in 1906 that the Dutch Creek region in Mineral County was to be opened for mining claims, Lydia arranged a hasty trip back home. When the kick-off blast rang out at noon on October 29, Lydia and a female friend were there among the eager throng of prospectors, aboard their own horse-drawn wagon. Off they dashed—plunging over rocks and boulders, fighting their way through desert scrub. Fourteen miles and a few hours later, Lydia had successfully staked out her own piece of the desert: a 600-by-1500-foot mining claim near the fabled Dutchman’s Creek Mine.

Lydia’s claim eventually proved worthless. But, self-promotional genius that she was, she milked the experience by penning a long, humorous article about her adventure for the “San Francisco Call.” She had been, she proudly pointed out, the first female locator at Dutch Creek. And it had been her wagon carrying the 25 pounds of Hercules powder to the starting line for the opening signal.

Back in Washington, D.C., Lydia somehow wrangled a position with the Department of Agriculture. Her job was to “spread the gospel of the desert” by writing and lecturing, educating the “people of the great east on the advantages of cooperating with the people of the big west,” as she put it.

RIGHT ON

Lydia treasured her role as a journalist. Memberships in the Women’s National Press Association and the International League of Press Clubs became proud feathers in her cap. She wrote passionately and frequently on environmental topics, including the devastating effects of deforestation. One article urged women in particular to step forward to save natural resources from “rapacious waste.” Men, she wrote, were “too busy building railroads, constructing ships, [and] engineering great projects” to understand the need to protect natural resources.

By her own account, at least, Lydia developed close friendships with Presidents Roosevelt and Taft, and became a frequent visitor at the White House. That version may have been something of a “Lydia-ism”—more puffery than fact.

And then came 1920. With ratification of the Nineteeth Amendment, women all across the country finally secured the precious right to vote (Nevada had been several years ahead of the suffrage curve, allowing women to vote in local races in 1915, and in state contests in 1916).

It was the dawn of a new era. And the exciting possibilities of politics weren’t lost on Lydia. She threw her hat in the political ring in 1921, declaring herself a candidate for the Republican nomination for a U.S. Senate seat for Nevada.

With four competitors vying for the nod and no serious financial backing, Lydia faced a seriously uphill battle. Undeterred, she set out to present her case in person to voters across Nevada. She hitched rides when she could, pressing on by foot when she couldn’t. In one especially brilliant move, she sweet-talked a traveling circus into letting her tag along with them. Not only did the circus offer a free lift between towns, it drew large crowds at every stop. The stunt drew national attention. Quipped one Illinois newspaper: “Whether she is nominated or not, it can not be denied that oratorical sideshowing is unsurpassed training for Congress.”

Not surprisingly, Lydia didn’t win the nomination at the 1922 convention. It would be nearly another century before Nevada would have its first woman senator; Catherine Marie Cortez Mastro was sworn in Jan. 3, 2017.

Lydia’s concession speech was gracious—and typical Lydia.

“The genuine old-time Nevada spirit was manifest everywhere I went,” she enthused. “I appreciate the fair play and good fellowship of all the candidates. I heartily congratulate all those who were fortunate enough to receive the party nomination and I will do all I can to help elect them.”

Lydia passed away in Los Angeles less than seven years later, on March 6, 1929. She’d been caught outside in a wind- and rainstorm, and a simple cold turned into pneumonia. She was just 61 years old. Lydia’s body was returned to Nevada, and she was buried in the family plot at historic Genoa Cemetery.

Shy and retiring she may not have been. But what a life she led.

Prospector. Writer. Conservationist. Would-be politician. Filled with confidence in her own abilities. Tireless champion of causes she believed in. Lydia Adams-Williams embraced adventure and refused to let rigid roles define her.

She was, in so many ways, a daughter of Nevada.