What’s In A Name?

February – April 2022

The backstory of how eight Nevada towns earned their names.

BY CORY MUNSON

Just like superheroes, every town’s name has an origin story. Some are straightforward: Mesquite is named for a tree found in the region; Carson City is named after the pioneer Kit Carson. For others, the tale has a little more to it: Yerington, for example, was originally called Greenfield, but had to be renamed when the postal service said there were already too many towns called that. Here’s a look at other towns where the story is disputed, steeped in legend, or just downright fun.

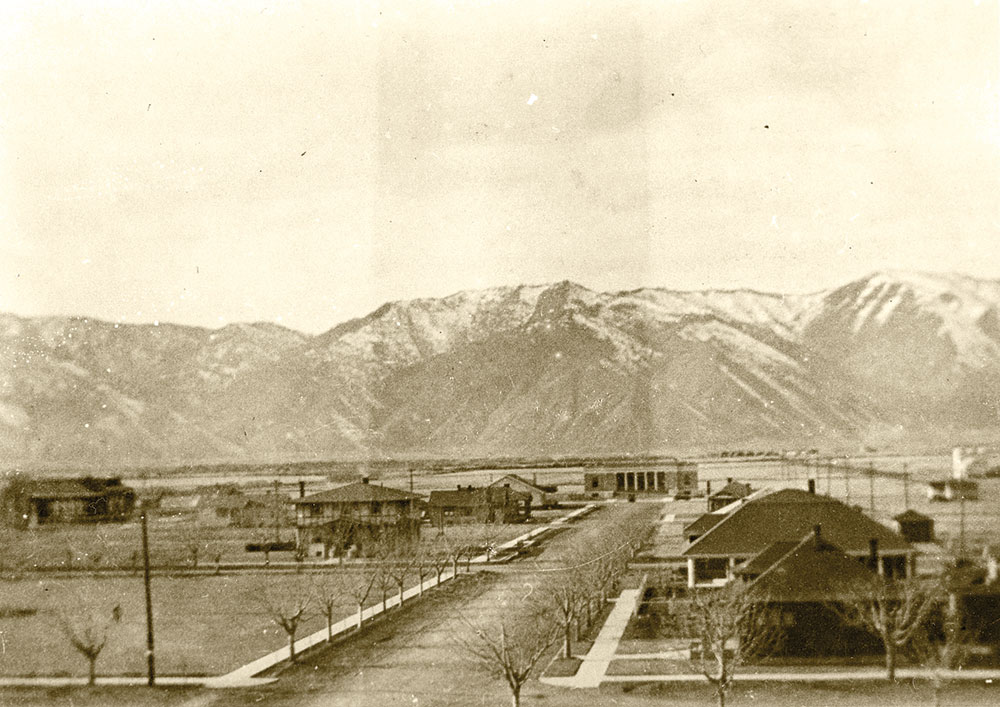

MINDEN

MINDEN

“Fred” Dangberg Jr. was delighted when the Virginia & Truckee Railroad (V&T) asked if they could build a station on his ranch in 1904. He had inherited the land from his father, a German immigrant who moved to Nevada and built a vast ranching empire. Dangberg was a savvy businessman and knew that a railroad would be a boon for the family estate. He immediately agreed to donate the land and then began to draw up plans for the town he would build around it.

His first instinct was to call the town Halle in honor of his father’s German birthplace. However, Henry Yerington—vice president of the V&T—was worried people would end up calling the town Hell. The two compromised and picked another German city called Minden. It is unclear if they chose Minden because it sounded nice or if it had something to do with Fred’s father—Halle and Minden are 180 miles apart.

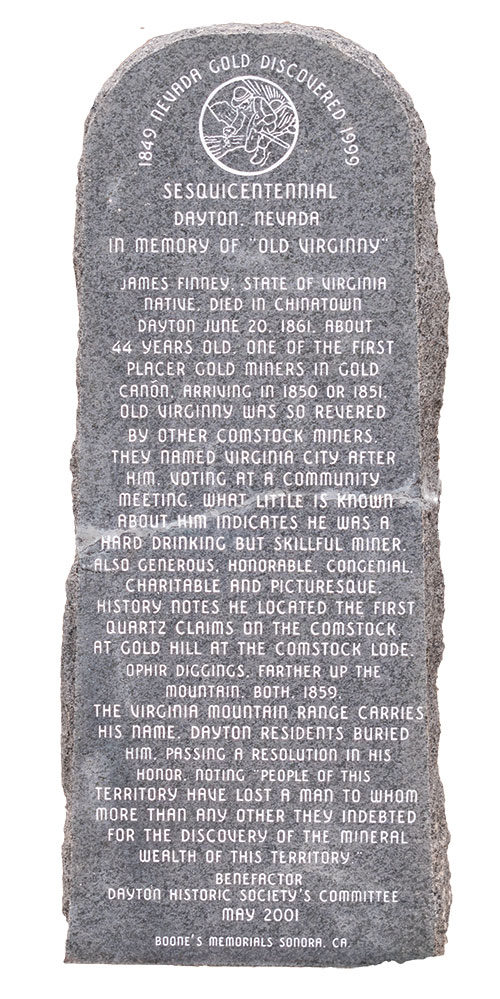

VIRGINIA CITY

Virginia City received its name when it was but a meager mining camp, allegedly during an intoxicated outburst by one of the camp’s first residents: Virginia native James Fennimore.

According to legend, Fennimore—who went by the name Old Virginny—was returning home after a night of drinking. Upon entering his cabin, Fennimore tripped and broke his bottle of liquor. He slowly raised himself to a kneeling position, pointed gravely to the broken glass, and declared in a commanding voice something along the lines of, “I baptize this place Ol’ Virginny Town.”

There is certainly no way to prove the veracity of this tale, but it makes for a good story; Dan De Quille even relates it in his history of the Comstock. Little is known about James Fennimore. He died in Dayton in 1861 after another night of hard drinking. The inscription on his memorial tells us he was a skilled miner, beloved among his cohort, and among the first to strike a claim on the Comstock.

INCLINE VILLAGE

INCLINE VILLAGE

To get to the Comstock’s silver, mines had to be carved into the surrounding hills. Scaffolding was needed to keep the vast network of tunnels supported, but good timber was scarce in the Great Basin. The trees they needed grew on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada—the other side of the mountain. To bring the wood to the Comstock required a marvel of 19th century engineering: a rail line called The Great Incline of the Sierra Nevada.

The 1,400-foot rail line was constructed on the north shore of Lake Tahoe. To process the trees, a mill town—named Incline Village after the rail—was built. After milling, the boards were loaded onto a steam-powered winch and carried up a staggering 35-degree slope. Once atop, the lumber was loaded into a flume, and gravity sent it down the other side of the Sierra.

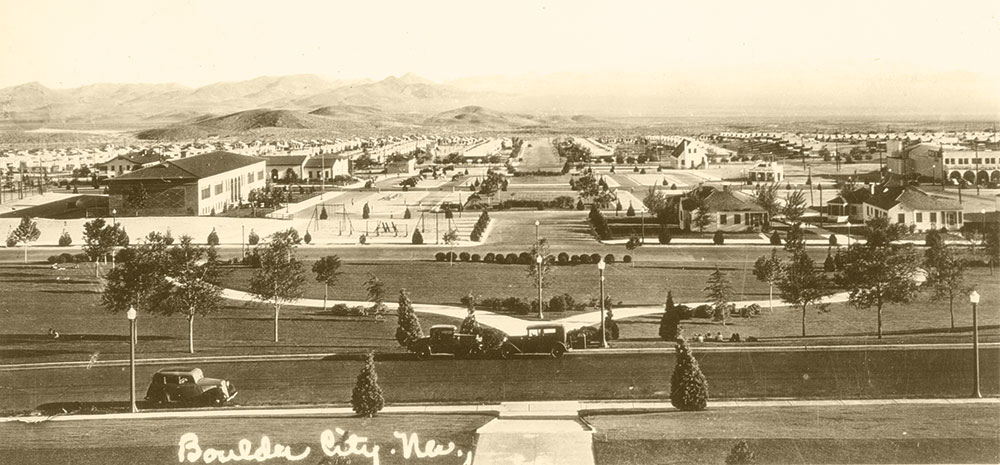

BOULDER CITY

Boulder City was established by the U.S. government to house the workers that built America’s largest dam. The town is named after Boulder Canyon, which was first identified as an ideal location for the dam. Surveyors later determined Black Canyon 20 miles downstream as a better site, but by then Boulder City had more than 4,000 residents.

During the dam’s construction, it was called both Boulder Dam and Hoover Dam. Hoover was an unpopular president, and it would take more than a decade for the official name to stick. When the project was completed, the government handed Boulder City over to the state, and it became a charming town named for a canyon without a dam and a dam with a different name.

During the dam’s construction, it was called both Boulder Dam and Hoover Dam. Hoover was an unpopular president, and it would take more than a decade for the official name to stick. When the project was completed, the government handed Boulder City over to the state, and it became a charming town named for a canyon without a dam and a dam with a different name.

JARBIDGE

The beautiful, remote mining village of Jarbidge lies in a narrow canyon in the extreme northeast of the state. Long before the arrival of white settlers, the area was a popular hunting ground for the Shoshone. The hunters believed a giant called T’sawhawbitts—anglicized to Jarbidge—lurked in the canyon. The creature would prey on victims that strayed too far from camp, trap them in his basket, then devour them at its home in a nearby crater.

TONOPAH AND PAHRUMP

Tonopah and Pahrump share a root word from the Shoshone language: “pah,” meaning water. Pahrump translates to “water rock” referring to the area’s many artisanal wells. Tonopah loosely translates to something like “brush water,” which could refer to the mountain mahogany or greasewood near the creek where ore was first discovered by Jim Butler.  There is some confusion over the name Tonopah since the Shoshone language does not construct words in a way that would make Tonopah grammatically correct. It’s believed the word is a white settler construction, perhaps from Butler himself (who is alleged to have understood the language).

There is some confusion over the name Tonopah since the Shoshone language does not construct words in a way that would make Tonopah grammatically correct. It’s believed the word is a white settler construction, perhaps from Butler himself (who is alleged to have understood the language).

JACKPOT

Jackpot was founded shortly after Idaho made gambling illegal in 1953. To accommodate the Gem State’s slot players, Idaho casinos moved their operation to the Nevada side of the border. By 1958, the community had a population large enough to warrant a town name. It had been informally called Horse Shu after the area’s first casino, but there was little agreement on an official name. After receiving no formal answer, Elko County christened the town Unincorporated Town No. 1. This spurred the casino owners to come up with something a bit more appealing, so they settled on Jackpot.

ELKO

Add northeastern Nevada’s largest city to the “nobody knows” pile. There are three theories for how Elko got its name. First, it’s possible that Elko is a Shoshone word for “white woman” because—apparently—that’s where they first saw one. Second, the name might refer to the region’s elk population, but with an ‘o’ to make it sound fancier. The third—and most likely—is that railroad operators preferred pithy names for their stations. Since Elko was a fairly common name for railroad towns in other states, the new railroad town in Nevada might as well have it, too.