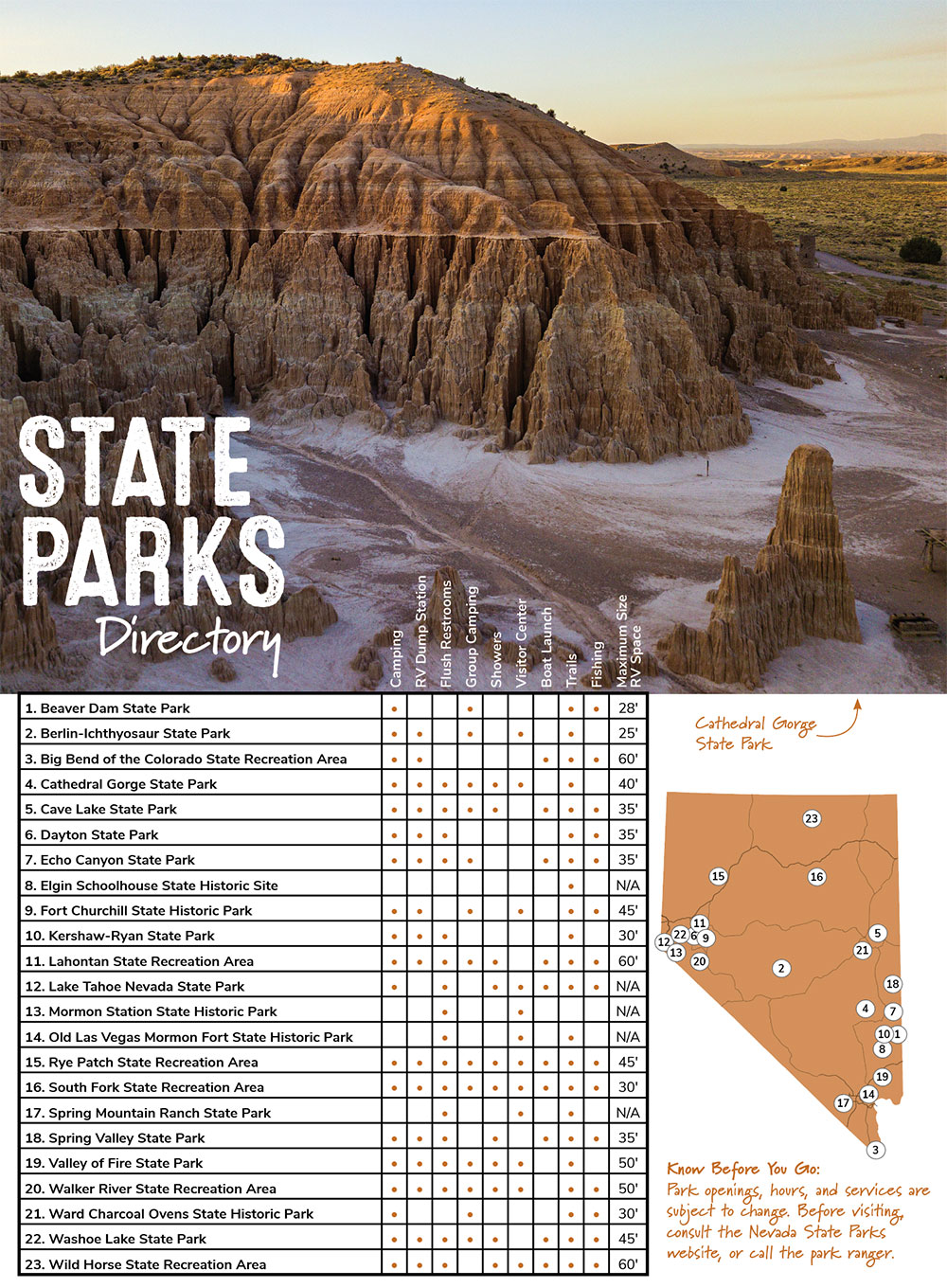

Nevada’s State Parks

February – April 2022

Discover history while making memories at these parks.

Nevada’s parks celebrate the Great Basin’s natural and human history, and for this issue, we’re zeroing in on ones that tell the story of the state from prehistory to today. Get ready for a trek through time; along the way you’ll meet ancient reptiles, tour military forts, and hang out in pioneer pit stops.

MORMON STATION STATE HISTORIC PARK

MORMON STATION STATE HISTORIC PARK

When the 1849 gold rush began, Nevada was entirely unsettled by pioneers and served as mere pass-through country for fortune-seekers streaming toward California. This would all change in 1851 when John Reese, a shopkeeper from Salt Lake City, set up a small trading post in the eastern foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

One year earlier, a Mormon contingent had built an ad-hoc, roofless shelter to sell supplies to settlers preparing to cross the great Sierra Nevada. Though this group had limited wares, business boomed: the nearest town—Salt Lake City—was 500 miles away, so scarce goods could be sold at a premium. One of the men from this group returned to Salt Lake and told John Reese about his adventure. Reese saw the opportunity for great profit and immediately set off to Nevada.

Reese set up his trading post right on the California Trail, thereby establishing Nevada’s first non-indigenous settlement. Weary travelers could find fresh horses, a blacksmith, general wares, hot meals, and comfortable beds—all available at a high price. Originally called Mormon Station after the Utah men who ran it, the trading post and fledgling community was renamed Genoa in 1854.

A Walk in the Park

Though the original buildings were destroyed in a 1910 fire, visitors can enjoy the reconstructed trading post as it appeared 170 years ago.

Within the park are shaded, grassy areas with picnic tables, a group pavilion that can accommodate up to 300 people, and several excellent hiking trails and wildlife viewing opportunities.

The park also houses a replica stockade and a museum that contains a wealth of pioneer artifacts.

FORT CHURCHILL & BUCKLAND STATION STATE HISTORIC PARKS

FORT CHURCHILL & BUCKLAND STATION STATE HISTORIC PARKS

Fort Churchill was a U.S. Army fort built in 1861 to provide protection for immigrants, mail carriers, and the small communities that dotted eastern Nevada. Before its construction, tensions between settlers and the area’s tribes—the Paiutes and the Bannocks—were high, culminating in violent encounters and pitched battles.

When the adobe fort was completed, it became a supply depot for the Union army. As the area became more developed and tensions abated, Fort Churchill was abandoned after only a decade of use.

Repurpose, Reuse, Recycle

Repurpose, Reuse, Recycle

In 1870, the disused site, including the adobe walls, barracks, and storehouses, were auctioned off and sold for $750 to Samuel Buckland. Buckland had moved to the area a decade earlier, purchasing a plot of land on the Carson River not far from the fort.

As construction materials were hard to come by, Buckland began dismantling the fortification to build his own fashionable two-story ranch house. The 19-room estate served as a travel lodge and residence for the large Buckland family and included a ballroom, classroom, and two parlors.

Buckland Station would change hands throughout the 20th century before being sold to the State of Nevada park system in 1997. Today, visitors can visit the remains of the old fort and tour the manor, explore walking trails, fish, and more.

OLD LAS VEGAS MORMON FORT

OLD LAS VEGAS MORMON FORT

In 1855, 30 Mormon missionaries entered Las Vegas Valley with a critical task issued from Salt Lake City: create a permanent Mormon settlement along the southern road to California. The party broke camp at Las Vegas Creek—the only free-flowing creek in the desert valley—and began construction of a fort.

The square fort was built from adobe: four walls, each 150 feet long, with defensive bulwarks and two-story rowhouses within. The missionaries created an irrigation system for farming and built services for weary travelers, including a post office and general store.

The Mormon experiment was not to last long, however: tensions within the group dissolved the project after two years, and the fort was left to decay for nearly a decade.

In 1865, the fort and its surrounding land was developed into a large ranching operation. In 1902, the ranchland was sold to the railroad, and the area’s first rail line was constructed. From these humble beginnings, the valley would quickly develop into one of the West’s largest cities.

Nestled in the Neon Capital

Located less than one mile from Fremont Street, Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort features perhaps the most dramatic time-travel experience in the state. Visitors can step from the 21st century into the 19th at the reconstructed fort.

The visitor center offers exhibits and artifacts with a history of the area that extends beyond the days of missionaries and ranchers: Las Vegas Creek has served as an oasis to many groups over millennia, including Paiutes, Spaniards, and Mexican traders. The museum also covers the rise of Las Vegas, the construction of the Hoover Dam, and life in the valley up to modern day.

BERLIN-ICHTHYOSAUR STATE PARK

BERLIN-ICHTHYOSAUR STATE PARK

During the American Civil War, a group of prospectors deep in the hills of central Nevada found silver in Union Canyon. Mining camps followed, which quickly grew into a community of tiny towns.

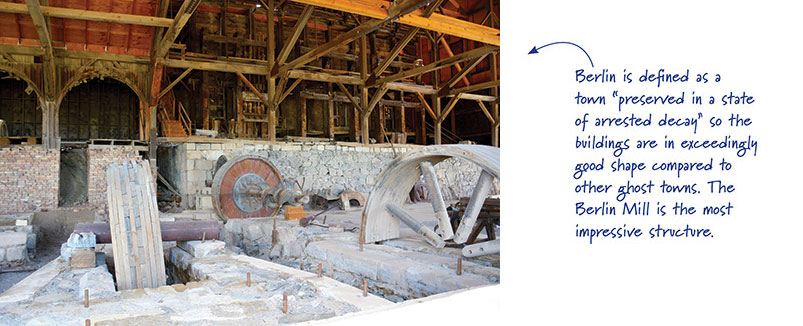

A few decades later, gold was discovered, and in 1896 the Berlin Mine was established. The town of Berlin enjoyed a decade of prosperity as miles of ore-filled tunnels were dug—by hand—in the hillside. At its peak, Berlin had a population of 300 people, and locals enjoyed all the trappings of modern life including grocery stores, a union hall, a post office, and an infirmary.

In all, about 42,000 ounces of gold were extracted near Berlin—a strong showing given the town’s small population. However, by 1911, the winds of fortune had drifted, and prospects dried up. The town was abandoned, its residents moving on to the next big strike. Berlin was returned to the desert, and possibly would have fallen into obscurity if not for another type of mineral hiding just below the surface: fossils.

New Digs

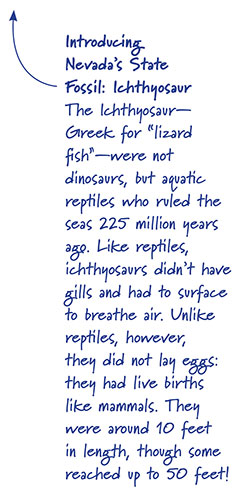

In 1928, Dr. Siemon Muller was surveying the terrain near the ghost town of Berlin when he discovered the fossilized remains of a large creature. The find stayed quiet until 1952, when Fallon resident Margaret Wheat gathered some fossils and brought them to the attention of the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology. Soon, paleontologists were on the site, and quickly uncovering 40 specimens—the largest concentration of ichthyosaur fossils in North America.

Wheat continued working with the paleontologists and advocated for the site to become a state monument, which was granted by the governor in 1957.

Wheat continued working with the paleontologists and advocated for the site to become a state monument, which was granted by the governor in 1957.

Grand Reopening

The park has undergone a complete restoration project and is set to open in early 2022. Visitors can take the Fossil House tour or go on a self-guided exploration of the park including the ghost town. The park offers plenty of opportunities for hiking, picnicking, and camping.