Spirited Adventures

February – April 2022

Nevada’s distinct history is borne by the nearly 600 towns that rose and fell before the 1900s even had time to stretch its legs. The gold and silver fever that struck the nation resulted in a clamor that touched nearly every corner of the state. While most towns bore fruit only for short periods, they literally left their mark on the state’s landscape. Many ghost towns may have no residents, but they are still full of stories, if you listen closely.

Nevada’s distinct history is borne by the nearly 600 towns that rose and fell before the 1900s even had time to stretch its legs. The gold and silver fever that struck the nation resulted in a clamor that touched nearly every corner of the state. While most towns bore fruit only for short periods, they literally left their mark on the state’s landscape. Many ghost towns may have no residents, but they are still full of stories, if you listen closely.

In this issue: Southeast Nevada

JACKRABBIT

JACKRABBIT

Just off U.S. Route 93, a Nevada historical marker announces Jackrabbit, but tall juniper and pinyon pines do their best to hide its remains. The town’s story, if true, begins with one of the luckiest Nevadans ever. Lore states a prospector bent down to pick up a rock to throw at a jackrabbit, only to find himself holding high-grade silver. A small town sprung up in 1876, but by 1893, operations halted. Look for a massive mineshaft, complete with ore cart tracks that protrude from a giant shaft. The cold air coming from the mineshaft feels like  someone turned on a powerful air conditioner. There are also remnants of a suspended aerial tram used to transport ore from the nearby silver camp of Bristol.

someone turned on a powerful air conditioner. There are also remnants of a suspended aerial tram used to transport ore from the nearby silver camp of Bristol.

BRISTOL WELL

A short drive from Jackrabbit, Bristol Well was the support community for the Bristol mining camp. In 1872, a furnace was built to treat silver-lead ore from the nearby mines, and by 1880, the town had a five-stamp mill, smelter, and three charcoal kilns. By 1890, the mines were extracting copper, leading to a population of around 400 before mining ended in the 1910s. The beehive-shaped kilns are in rough shape, but still an awesome sight. Treat them with respect and don’t climb on them.

HELENE

Located just 1 mile to the north of Delamar (see page 98) are the remains of the tent camp of Helene—founded around 1892. Though the operation was much smaller than that of Delamar, Helene had a post office and a newspaper called “The Ferguson Lode.” The town was only active for a couple of years, fading before the start of the 20th century. There are several remnants of the town including stone buildings, wooden mining structures, and the entrance to the Magnolia Mine. Though not much remains of the town, the view at Helene is incredible.

PIOCHE

While certainly not a ghost town, Pioche is too cool (and close by) to overlook. “Nevada’s liveliest ghost town” is a small, picturesque community just off U.S. 93. The friendly, inviting atmosphere found today stands in stark contrast to its reputation as the roughest, toughest mining town in the Old West. In the early 1870s, a silver boom catapulted Pioche into one of the largest mining camps in the area. Gunslinging was a favorite pastime, which earned the town its notorious reputation. It’s said 72 people were buried before someone died of natural causes. Other must visits: make sure to check out the Million Dollar Courthouse and Boot Hill Cemetery’s “Murderer’s Row.”

PANACA SUMMIT CHARCOAL KILNS

An absolute must for intrepid adventurers, the kilns at Panaca Summit were built by pioneers in the mid-1870s and supported nearby silver mills. The kilns owe their roots to skilled stonemasons that quarried rhyolitic tuff from area outcroppings before shaping the rocks and assembling them with mud and mortar into the familiar beehive shape. The giant ovens were operated by Swiss and Italian woodcutters—known as the carbonari—who perfected the charcoal-making process in Europe and brought their skills to Nevada. Each stands about 20-feet tall, and they are in remarkable shape.

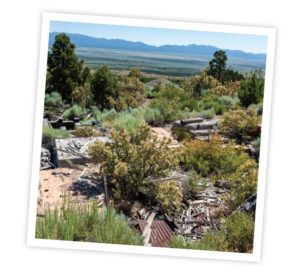

Delamar: The Silent Killer

The ghost town of Delamar is, for a state full of ghost towns, an unusual site. The town died almost a century ago, yet there are dozens of decaying structures, mine frames, stone huts, and debris piles covering miles of hills. It is a town that deserves leisurely exploration, and even a return trip. Some ghost towns leave few clues to the scale of operations, but it’s easy to get an idea of just how massive Delamar was.

The ghost town of Delamar is, for a state full of ghost towns, an unusual site. The town died almost a century ago, yet there are dozens of decaying structures, mine frames, stone huts, and debris piles covering miles of hills. It is a town that deserves leisurely exploration, and even a return trip. Some ghost towns leave few clues to the scale of operations, but it’s easy to get an idea of just how massive Delamar was.

Pahranagat Valley farmers struck gold in the area that would eventually become Delamar in 1890-91. The discovery initiated an onslaught of eager gold bugs, including Captain John De Lamar of Montana, who purchased prime claims in 1893 for $150,000. Soon after his acquisition, the town of Delamar quickly rose from the ground with many of the buildings constructed from native rock. Various businesses, a newspaper, post office, opera house, and 50-ton mill capable of handling up to 260 tons of ore per day provided work, but the American dream wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

Because of improper ventilation and high silica content in the mines, dust became deadly. Miners unlucky enough to inhale the dust developed a fatal condition known as silicosis, which included such symptoms as severe coughing spells. The situation was so serious that the lethal particles became known as “Delamar dust,” and the town was labeled “The Widow Maker.”

By 1897, Delamar’s population reached 3,000, and the town was the largest ore producer in the state. However, in 1900 a fire destroyed much of the town, and just two years later, Captain De Lamar sold his mines. New owners managed to pull a few more millions out of Delamar, but by 1909, the last mine closed. After a short revival from 1929-34, the town became a ghost.

Getting to Delamar takes a bit of extra effort, so pack your high-clearance 4WD vehicle with plenty of water, food, and gas, because it’s worth it. The town is about 12 miles off U.S. 93, and the road is a bit bumpy although not treacherous. Always recreate responsibly (see page 118) and tell someone where you’re going.