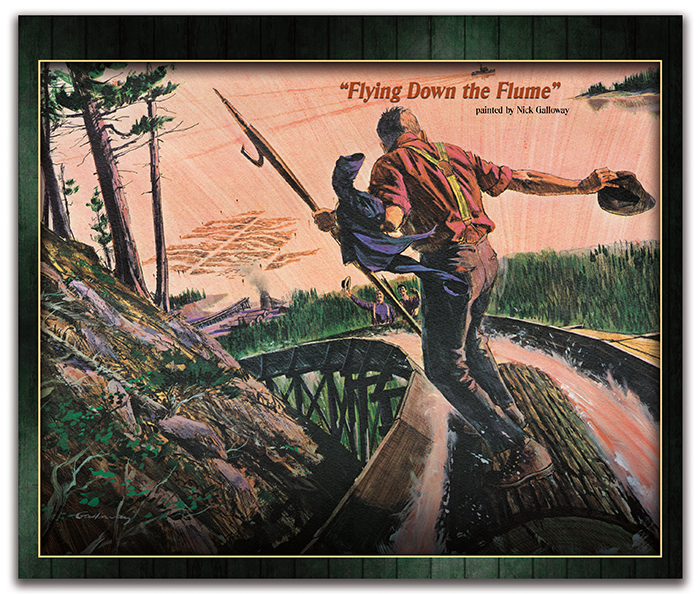

Five Fools On A Flume

January – February 2017

A bonehead challenge in Nevada’s ‘wooden wonder’

BY BOB SAGAN

That ancient adage—a fool and his money are soon parted— might have found its purest form of expression in a little-known incident that occurred in 1875 Nevada, had it not been for a hefty dose of dumb luck. The incident in question was triggered by the curiosity of an East Coast journalist who decided to visit The Comstock and see what the mining boom was all about. A chance invitation to see how the lumber that built the mines was being moved from Lake Tahoe was extended, and he ended up with a story he never could have imagined.

TIMBER, THE CRITICAL COMPONENT

As the Comstock mining companies gouged ever deeper into the mineral-rich earth, the need for timber to shore up the excavations grew critical. Pressure in the underground mines, some of which extended as far as 5 miles, made cave-ins common. The mines needed the steady stream of lumber and cordwood supplied by a 12-thousand-acre tract on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada to continue operating.

As the Comstock mining companies gouged ever deeper into the mineral-rich earth, the need for timber to shore up the excavations grew critical. Pressure in the underground mines, some of which extended as far as 5 miles, made cave-ins common. The mines needed the steady stream of lumber and cordwood supplied by a 12-thousand-acre tract on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada to continue operating.

Harvesting the lumber was one thing, but getting it to the mines was something else. The terrain was steep and irregular, and footing was treacherous. The road—dusty and choking in dry weather—became muddy and virtually impassable in the rain and snow. So lumberman J.W. Haines of Douglas County came up with a solution that turned out to be a pivotal point in the continuing development of The Comstock.

A WOODEN WONDER

Haines’ brainchild was a V-shaped flume—nothing more than a giant trough of 2-inch-thick planks, 2-feet wide and 16-feet long, nailed together into a V. The slanting sides of the flume allowed the lumber to float freely on a rapid stream of water, as opposed to the conventional dry chutes and square-box flumes of the day.

The flume contained 2-million feet of lumber and 28 tons of spikes and nails. It operated 70-feet above ground in some places, and could transport up to a half-million feet of lumber daily. Employing 200 men, the flume’s builders completed 15 miles of trough, from Hunter’s Creek on Mount Rose— between Lake Tahoe and Reno—to Huffaker’s Station and the Virginia and Truckee Railroad terminus in Washoe Valley. They did it in a scant 10 weeks at a cost of $250,000.

Reportedly, the flume did the work of 2,000 horses, and quickly became a kind of “wooden wonder of the West.” It sparked some curiosity as far east as New York City; no small feat, since even then New Yorkers were not easily convinced anything noteworthy was to be found west of the Hudson. Still, due to its riches, Virginia City in the 1870s was considered one of the most important cities between Chicago and San Francisco.

In the summer of 1875, H.J. Ramsdell, a reporter for the New York Tribune, had heard tales of Nevada’s great flume and decided to see it for himself. Ramsdell was hosted by James G. Fair and J.C. Flood, both principals in the company that built the flume and multimillionaires who had made their fortunes in the mines.

Understandably proud of their operation, Fair and Flood were eager to showcase it for the journalist from the big city and invited Ramsdell to inspect the construction up close. Had the reporter guessed at the time just how close, he might not have accepted so readily.

Ramsdell was impressed by the operation’s simplicity, and also its immensity. He was fascinated by the fact that the 15 miles of trough actually ended at a point only 8 miles away as the crow flies. Like a huge wooden snake, the flume twisted and turned for an additional 7 miles in order to negotiate the irregular landscape.

LOSING THEIR SENSES

What happened that summer’s day in 1875 remains sketchy. It’s hard to understand how otherwise intelligent, pragmatic businessmen would do what they decided to do. Some say Fair and Flood took the occasion to “baptize” their flume with a ceremonial ride. More likely, the two men—showing off for the reporter—dared each other to ride the flume, and Ramsdell and John B. Hereford (who directed the project’s construction) were sucked into the challenge.

Lumberjacks and mill-hands at the flume entrance hurriedly rigged together two V-shaped “boats,” which were no more than narrower versions of the flume itself. The fronts of the “hog troughs,” as they were called, were left open, while the rear portions were closed with boards, against which the water currents would act as propulsion. Narrow boards served as seats. Fair and Ramsdell would “captain” the lead boat. At the last minute, they requested a volunteer from the workers standing around—someone to accompany them who was familiar with the flume’s meanderings. An unnamed, ruddy-faced carpenter, whose coworkers claimed had a hearty attraction “to the grape,” agreed to go.

It was a dumb decision on top of an already dumber decision. The second boat would carry Flood and Hereford. Apparently, up until that point, no one had considered that the second boat, with a lighter load, could eventually overtake and crash into the lead vessel while on the descent.

NEARER MY GOD TO THEE

As soon as the passengers hit their seats, they took off like human bullets in the furious flow of flume water. The makeshift boats bumped and careened wildly down the irregular course, over deep rocky gullies and around curved sections built along the sides of sheer cliffs. The trip might be compared to a ride on a modern-day roller coaster with the attendant asleep at the switch—except there was no attendant to do the switching…or even the sleeping. The occupants of the two hog troughs, by this time hurtling down the flume at breakneck speed, would later admit they divided their time between cursing their stupidity and making peace with their maker.

As soon as the passengers hit their seats, they took off like human bullets in the furious flow of flume water. The makeshift boats bumped and careened wildly down the irregular course, over deep rocky gullies and around curved sections built along the sides of sheer cliffs. The trip might be compared to a ride on a modern-day roller coaster with the attendant asleep at the switch—except there was no attendant to do the switching…or even the sleeping. The occupants of the two hog troughs, by this time hurtling down the flume at breakneck speed, would later admit they divided their time between cursing their stupidity and making peace with their maker.

Ramsdell described it later for his New York readers: “You have nothing to hold on to; you have only to sit still, take all the water that comes—drenching you like a plunge through the surf—and wait for eternity.” James Fair put it a little more eloquently (though perhaps a trifle overstated): “My belief is that we annihilated both time and space.”

At one point, the lead boat carrying Fair, Ramsdell, and the carpenter hit a submerged object and stuck momentarily. The abrupt stop catapulted the carpenter out of the vessel and into the flume waters a few feet ahead. This sudden lightening of its load permitted the craft to break free, and Fair managed to drag him back into the boat. With that brief delay, the second, lighter boat was able to gain on the lead craft, which increased the likelihood of a collision.

If it occurred at certain points along the trestle, the men could be thrown out against the jagged rocks below. At times, where the flume was steepest, the speed was great enough that the passengers could hardly breathe. Ramsdell later claimed he had been in 80-mile-an-hour gales and never experienced the suffocating sensations caused by the buffeting wind of their out-of-control descent. He compared the din to the “rushing of a herd of buffalo.”

AN UNWELCOME RENDEZVOUS

Then, possibility became reality. With the end of the trip in sight, the second boat carrying Flood and Hereford plowed into the first vessel with a jarring impact. Flood got the worst of it, pitching forward unceremoniously on his face. The others

Then, possibility became reality. With the end of the trip in sight, the second boat carrying Flood and Hereford plowed into the first vessel with a jarring impact. Flood got the worst of it, pitching forward unceremoniously on his face. The others

fared only slightly better. The five were grateful that the collision occurred in a relatively slow and safe area of the flume. Scant seconds before, they had been traveling over a particularly hazardous stretch, where the outcome could have been disastrous. As it was, the bruised and battered men eagerly jumped clear as the boats slowed down near the run’s terminal. The workers at the end of the flume were completely caught off guard to see their usually dapper bosses showing up at camp in such a bedraggled state. They were even more surprised given their mode of transportation.

Understandably, none of those involved would ever again engage in such timberland “tomflumery.” If it’s true there are no atheists in foxholes, then so it’s true that the five men bucking the flume that day in 1875 were as devout as they ever would be. Ramsdell returned to the New York Tribune to report to his readers that something of substance did indeed exist outside the confines of New York.