Ancient Nevada, Part 1: Water

January – February 2017

First of six-part series reveals our most precious resource wasn’t always in such short supply.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

If you were to stand on the shore of Pyramid Lake and gaze across seemingly endless miles of beautiful blue water, it would be hard to imagine that it could get any larger. But the northern Nevada lake was once part of a much larger body of water that dwarfed modern ones in size.

Water has sculpted Nevada’s desert mountain ranges and created miles of barren lakebeds. It’s what gives animals and plants the ability to thrive, and is responsible for almost every natural landscape in the state looking the way it does. With enough time, water can cut rocks and erode entire mountains. And when it disappears, it can create endless miles of nothingness.

Just 10,000 years ago, a person could have sailed a boat from Hawthorne to Winnemucca without ever touching dry land. This fact gives some perspective of how much water we had, and just how different our modern landscapes and ecosystems are from those of ancient Nevada.

GLACIERS

This story begins with frozen water, and during the Pleistocene Epoch—which began roughly 2.5 million years ago and lasted until about 11,700 years ago—there was a lot of it. Though the most recent ice age took place during this time period, leaving many mountain ranges in Nevada covered in glaciers, the state wasn’t completely covered in ice sheets. Intermittent freezing and warming sculpted many ranges in the Great Basin, including the Snake Range and Wheeler Peak in eastern Nevada.

Queue the Holocene Epoch, which marks the end of the most recent ice age and continues to this day. Natural climate warming occurred and most glaciers in Nevada met their demise. The Wheeler Peak Glacier, however, is the last alpine glacier to survive in Nevada, though the National Parks Service estimates that with continued climate change the colossal ice structure could disappear in as few as 20 years.

Nevada’s climate during the Pleistocene and early Holocene Epochs was characterized by a pluvial climate, causing increased precipitation and reduced evaporation. The excess moisture and eventual temperature increase contributed to Nevada’s extensive lakes and rivers systems.

ANCIENT LAKES AND RIVERS

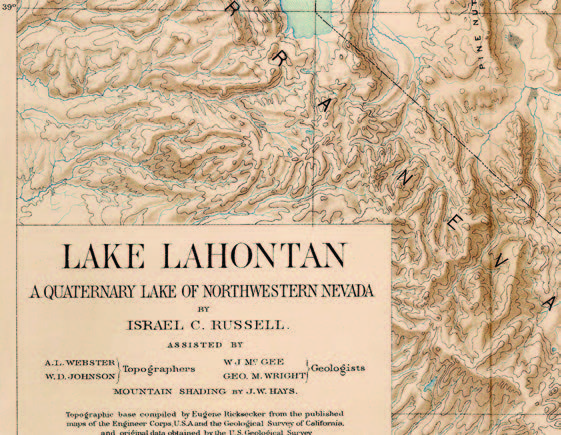

The most notable of these mammoth lakes was ancient Lake Lahontan. Today, remnants of Lake Lahontan still exist, though the size pales in comparison to the massive prehistoric water source that once covered much of northwest Ne- vada and a part of eastern California. At its peak during the late Pleistocene Epoch, the lake covered more than 8,600 square miles and reached a maximum depth of more than 500 feet.

Lahontan was created over several millennia, the result of several major river systems. Walker, Carson, Truckee, and Humboldt Rivers are responsible for filling basin after basin, causing many lakes to spill over into new areas. Water sources combined, eventually leading to the lake’s creation. Lake Bonneville was formed by similar means, with a sliver of the lake spilling into eastern Nevada.

Though Lake Lahontan did not make its way to southern Nevada, dry lakebeds are evidence that water played a key role in shaping the southern landscape, as well. And though the Colorado River only makes a brief appearance in the state, the colorful canyons it created are a reminder that Nevada’s landscape is at the mercy of this powerful element.

Another ancient waterway in the southern part of the state is the Amargosa River. This river flowed from the volcanic highlands near Beatty during the Pleistocene Epoch, making its way across the border into several California lakes, and eventually underground in Death Valley. The river still flows to this day, though mostly underground. It makes appearances above ground during periods of heavy precipitation.

THE GREAT BASIN

Explorer John C. Frémont coined the term Great Basin in the mid-1800s, using it to describe the hydrographic nature of the area as having no connection to the ocean. Generally, any water that lands on the west side of the Continental Divide will flow to the Pacific Ocean, and any on the east side will flow to the Atlantic, but the Great Basin is different. Water settles here, often flowing into alkaline lakes or underground aquifers, or simply evaporates. Walker Lake, located near Hawthorne, is a perfect example of the Great Basin’s imprisoning nature.

With no outlets, water fed to the lake via Walker River simply settles; the only way it has a chance of leaving is through evaporation or absorption. The lake is a remnant of ancient Lake Lahontan, though it hasn’t always been full of water since that time. Walker is believed to have dried up several times since the Pleistocene era, due to the river’s natural diversions over time.

Pyramid Lake, another remnant of ancient Lake Lahontan, has never dried up. Similar to Walker Lake, Pyramid has no outlets, giving its water salinity that is common among Great Basin lakes. And though Pyramid survives, many of these saline lakes didn’t, leaving behind beautiful watermarks.

PLAYAS

Over time, in the same places that trillions of gallons of water once stood, now there is none. Because water that settled in these places years ago had no place to drain, it simply evaporated, leaving a layer of salt on the surface. The Black Rock Desert, for example, was once submerged beneath Lake Lahontan, but is now a vast expanse of alkali nothingness. The playa is flat and barren nearly as far as the eye can see in some places. Nevada has numerous dry lakebeds dotted across the landscape, providing even more evidence that Nevada was once much wetter than it is today.

CYCLES

Water has had an enduring and often vicious relationship with Nevada. Colossal glaciers carved landscapes; ancient rivers rose from the earth; and lakes so large they are difficult to imagine dried up. Water has, and will continue, to shape Nevada.

Next issue, we’ll explore Nevada’s ancient civilizations and the important role they played in our state’s history.

Water, Water Everywhere – ANCIENT OCEAN

Though Nevada is a desert, it was once entirely submerged hundreds of millions of years ago. The state experienced everything from warm, shallow seas to deep ocean basins. Reefs were common, and evidence of their existence can still be found today in fossils. Animals such as the ichthyosaur once swam in the waters that covered the state, as did ancient plankton and fish.

LAMOILLE GLACIER

Lamoille Canyon in eastern Nevada is a good example of how time, temperature, and pressure sculpted many of the incredible landforms we know today. About 250 million years ago, two glaciers—each 1,000 feet thick—merged in the area that would become the canyon. During a period of hundreds of millions of years, the glaciers melted and refroze, creating natural dams and eventually Lamoille Creek, which carved out much of the canyon.

LAKE TAHOE

Lake Tahoe’s formation was a bit of a different story. The Lake Tahoe Basin was formed some 23 million years ago when massive faulting and lava flows created the perfect area to hold water. Over time, water from snowfall filled the massive basin, giving us the crystal-clear lake we still enjoy.