The Rise and Fall of Reno’s Chinatown

January-February 2018

Laborers suffered under reforms of Progressive Era.

BY EDAN STREKAL

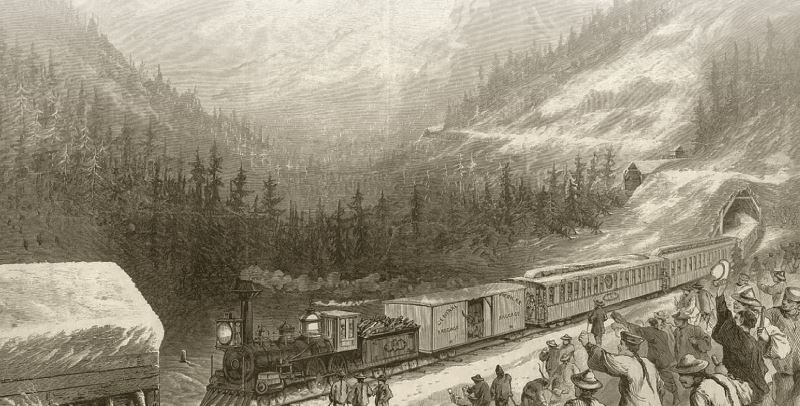

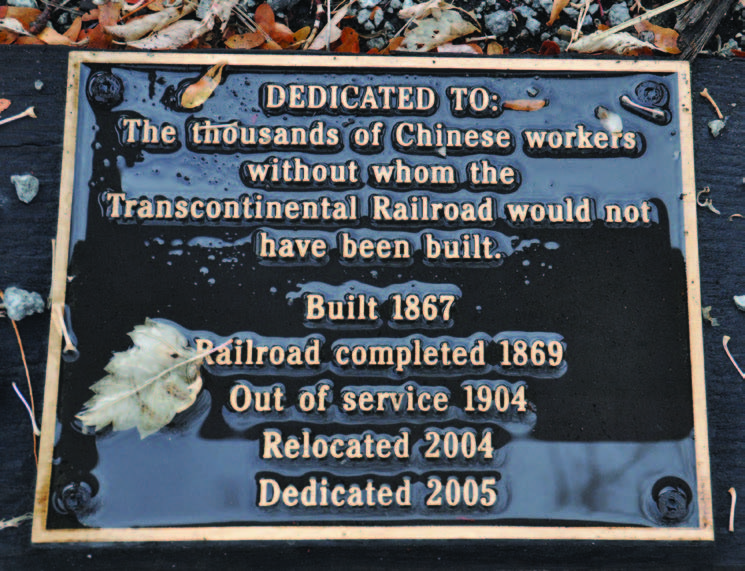

The Sacramento-to-Reno section of the Central Pacific Railroad was completed in the spring of 1868 and the many Chinese laborers who had risked life and limb laying track over the Sierra Nevada received final payment and were left along the line to fend for themselves. Many settled in Reno, where they constructed flimsy bare- wood structures at the crossroads of Virginia and First streets along the banks of the Truckee River and attempted to put down roots in the community they now called home.

On the morning of Nov. 2, 1908, however, Reno’s Chinese residents watched as an army of laborers armed with crowbars, sledgehammers, and axes descended on their community to raze all structures. Chinatown had been deemed a “physical and moral threat,” and a grand jury ordered its destruction. The events of 1908 place Reno within the larger context of Progressive Era (1900-1920) reforms that swept through many western cities.

BUILDING NEVADA’S BACKBONE

The Chinese presence in Nevada dates back as early as 1855, when Mormon settlers residing at McMarlin’s Station at the mouth of Gold Canyon hired 50 Chinese workers to dig a ditch to divert water for placer mining. Following completion of the ditch, the Chinese stayed and their settlement became known as Chinatown; it was renamed Dayton in 1861. With the discovery of The Comstock Lode, Chinese workers began turning up in larger numbers. Most worked as laundrymen, gardeners, servants, or cooks, because a resolution passed in 1859 forbade the Chinese from owning mining claims or working in underground mines in the Gold Hill District. Professor emeritus of Asian-Ameri- can studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Dr. Sue Fawn Chung, explains that formation of Chinatowns acted as a two-way street. Oftentimes, the white communities wanted the Chinese segregated, and in many cases Chinese residents who spoke little if any English preferred living with their countrymen in ethnic enclaves.

The Chinese presence in Nevada dates back as early as 1855, when Mormon settlers residing at McMarlin’s Station at the mouth of Gold Canyon hired 50 Chinese workers to dig a ditch to divert water for placer mining. Following completion of the ditch, the Chinese stayed and their settlement became known as Chinatown; it was renamed Dayton in 1861. With the discovery of The Comstock Lode, Chinese workers began turning up in larger numbers. Most worked as laundrymen, gardeners, servants, or cooks, because a resolution passed in 1859 forbade the Chinese from owning mining claims or working in underground mines in the Gold Hill District. Professor emeritus of Asian-Ameri- can studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Dr. Sue Fawn Chung, explains that formation of Chinatowns acted as a two-way street. Oftentimes, the white communities wanted the Chinese segregated, and in many cases Chinese residents who spoke little if any English preferred living with their countrymen in ethnic enclaves.

Unfortunately, the formation of an ethnic enclave or Chinatown was sometimes regarded as unwillingness to assimilate or adopt American institutions and customs. Reno’s Chinese residents at the time never exceeded 7 percent of the total population, but they supported a chapter of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), based in San Francisco, which offered legal support and protection to Chinese immigrants. Despite its small size, the population’s visibility during the 1870s and 1880s sparked fear and prejudice in some, and several anti-Chinese groups were formed, including local chapters of the Workingmen’s Party, the Order of the Caucasians, and a 601 vigilance committee.

Unfortunately, the formation of an ethnic enclave or Chinatown was sometimes regarded as unwillingness to assimilate or adopt American institutions and customs. Reno’s Chinese residents at the time never exceeded 7 percent of the total population, but they supported a chapter of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), based in San Francisco, which offered legal support and protection to Chinese immigrants. Despite its small size, the population’s visibility during the 1870s and 1880s sparked fear and prejudice in some, and several anti-Chinese groups were formed, including local chapters of the Workingmen’s Party, the Order of the Caucasians, and a 601 vigilance committee.

The Workingmen’s Party and the Order of the Caucasians were labor groups that emerged as a result of the deepening recession of the 1870s, the rise in labor unions in the U.S., and the growth of the Chinese population. The 601 Reno Regulators, on the other hand, was composed of businessmen and taxpayers who sought to maintain law and order within the community through extralegal means.

TRYING TO FIT IN

Chinatown functioned as an independent entity within Reno and many businesses catered to Chinese residents, while opium dens, laundries, gambling, and prostitution catered to the wider population. In the mid-1870s, the passage of anti-opium ordinances attempted to discourage drug use. Editorials in the Reno newspapers suggest residents were not necessarily concerned about Chinese opium usage, although if caught by law enforcement, perpetrators would be fined and/or jailed. An outcry arose, however, over the use of opium by white citizens, and according to Dr. Chung, many of the local anti-opium ordinances were passed as a result of white users frequenting dens. Reno’s prominent Chinese citizens also attempted to discourage opium use due to the negative image it painted of the community.

Chinatown functioned as an independent entity within Reno and many businesses catered to Chinese residents, while opium dens, laundries, gambling, and prostitution catered to the wider population. In the mid-1870s, the passage of anti-opium ordinances attempted to discourage drug use. Editorials in the Reno newspapers suggest residents were not necessarily concerned about Chinese opium usage, although if caught by law enforcement, perpetrators would be fined and/or jailed. An outcry arose, however, over the use of opium by white citizens, and according to Dr. Chung, many of the local anti-opium ordinances were passed as a result of white users frequenting dens. Reno’s prominent Chinese citizens also attempted to discourage opium use due to the negative image it painted of the community.

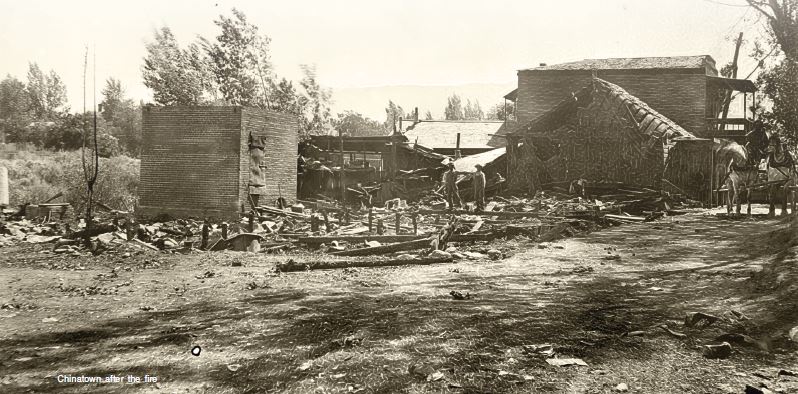

Tensions had been running high since May when the San Francisco-based firm Lung Chung & Company received the contract to construct the 33-mile Steamboat Ditch irrigation canal from Truckee into Reno. The Workingmen had condemned the Truckee and Steamboat Springs Canal Company for employing Chinese labor. On Aug. 3, 1878, a fire consumed the Chinese quarter. Coincidentally, the “Nevada State Journal” reported that the Workingmen’s Party had held a meeting that same evening to discuss and adapt a series of resolutions on “the Chinese question.”

The following day the fire was reported as an unfortunate accident. The Workingmen denied arson allegations and called for the wholesale removal of Chinese residents from Reno within 48 hours. City officials feared that forced removal could result in bloodshed, so they instead allowed the Chinese to relocate away from downtown.

NEW LAWS

Fortunately, few incidents of violence or physical hostility occurred in Chinatown for more than 20 years after the 1878 fire. Efforts to address concerns about the Chinese turned to legal action, and a successful boycott and expulsion of the Chinese from Truckee, California, in 1886 spurred renewed efforts in Reno to do the same.

Resolutions to replace Chinese workers with white workers were adopted and many local businesses obliged. Most Chinese residents saw little choice but to leave but those that chose not to were not forcibly removed. Between 1880 and 1890, Washoe County’s Chinese population dropped by more than 50 percent, to just 217.

By the turn of the century, reports of bubonic plague in Honolulu and San Francisco’s Chinatown linked the disease with the communities. When the Reno Board of Health was created, it was on high alert for signs of the disease. Reno city officials and residents were interested in attracting long-term investment, but

believed the town needed to rid itself of any depravities first. Many of the proposed banned activities and ramshackle structures were located adjacent to city hall and in Chinatown. City reformers proposed buying, razing, and then planting lawns and trees over these areas in an effort to restore desirability, morality, and promote recreation. Reformers were determined to clean up Reno.

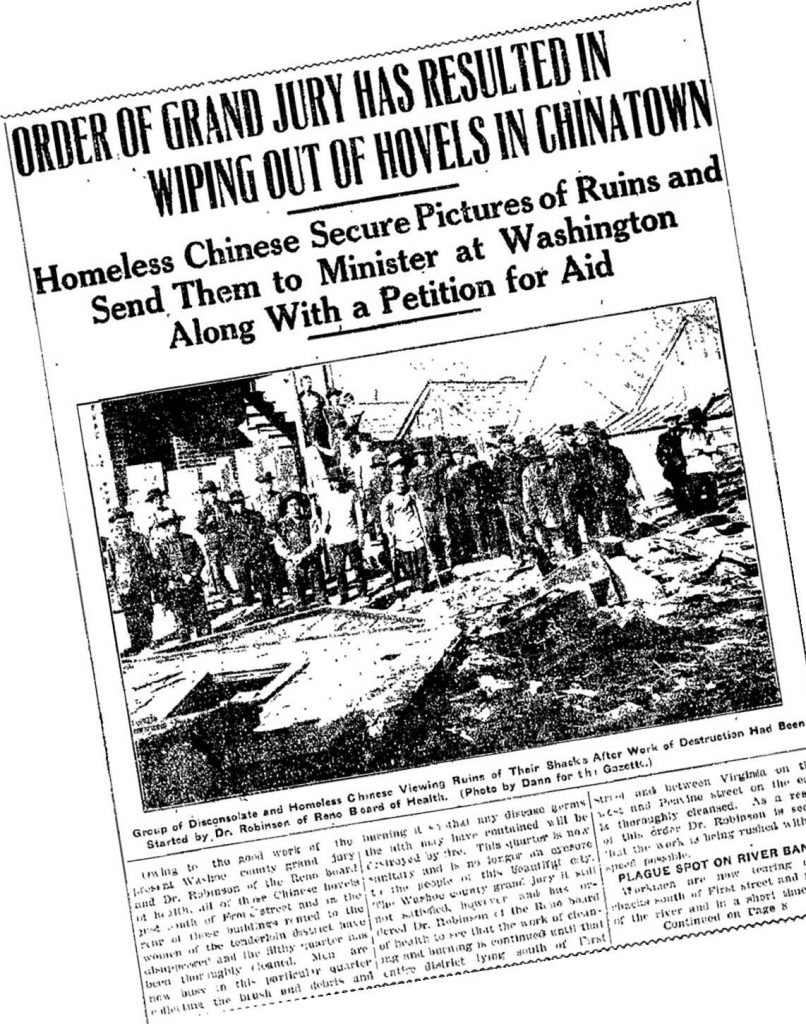

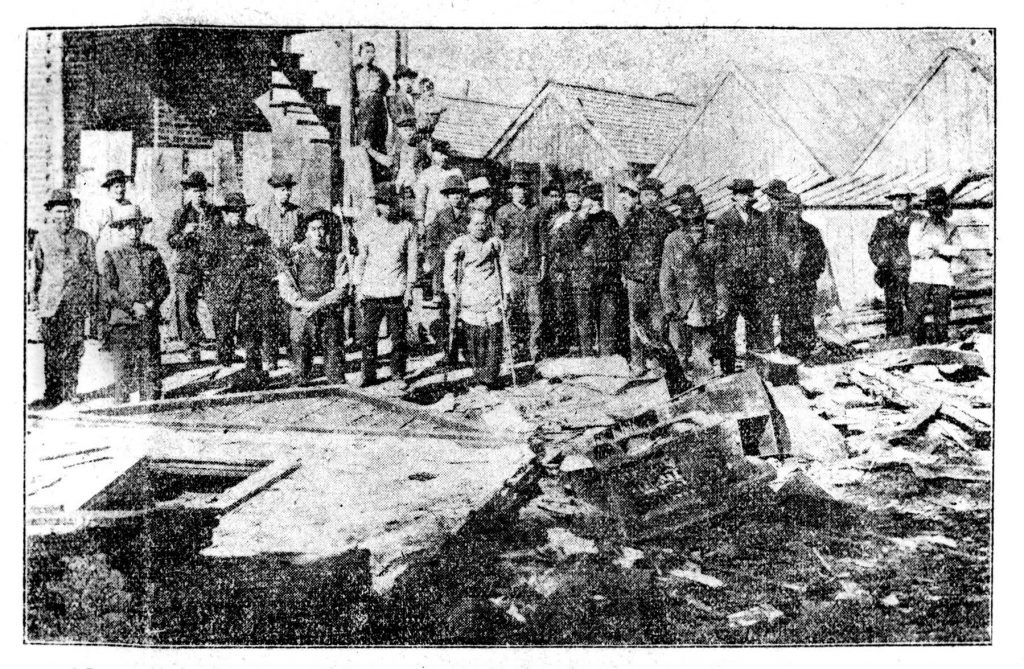

In November 1908, a Washoe County Grand Jury ordered the razing of Chinatown—a “disease-breeding place” according to Dr. James L. Robinson, of the newly formed Reno Board of Health. Only the joss house (a place of worship), and some of the more-frequented brothels that housed Chinese prostitutes were spared in the destruction. Crews then set to work clearing an avenue from Peavine Street to the newly-constructed bridge at Virginia Street. The 150 Chinese residents were left in the cold. Some remained, some left the area, and others moved in with relatives in Sparks

.

SOME REMAIN

The events in Reno created a stir along the West Coast, drawing protest from Washington State to San Francisco. The Reno Chinese community immediately reached out to the Chinese Consul and CCBA in San Francisco, and even forwarded a letter and photographs to the Chinese minister in Washington complaining that they’d been violently driven out of their homes. In December 1908, the Chinese of Reno hired leading Reno attorney, Judge W.D. Jones, to file a suit against the city for $7,000. It is unclear whether the lawsuit ever materialized because Reno city officials and Chinese representatives agreed that the city had acted within its rights.

The events in Reno created a stir along the West Coast, drawing protest from Washington State to San Francisco. The Reno Chinese community immediately reached out to the Chinese Consul and CCBA in San Francisco, and even forwarded a letter and photographs to the Chinese minister in Washington complaining that they’d been violently driven out of their homes. In December 1908, the Chinese of Reno hired leading Reno attorney, Judge W.D. Jones, to file a suit against the city for $7,000. It is unclear whether the lawsuit ever materialized because Reno city officials and Chinese representatives agreed that the city had acted within its rights.

Though Chinatown was mostly gone, a small Chinese population persisted along Lake Street including the joss house, and Chinese-owned casinos including the Cosmo Club and the New China Club. Eventually, Chinese-owned businesses—the office of the Chinese Nationalist Party, and a Chinese Free Mason Hall—were established around downtown. Dr. Chung suggests discriminatory laws passed in the 1870s and 1880s were largely ignored or forgotten by the 20th century. Slowly, the Chinese community and their institutions gained greater acceptance in Reno.

After many years, the Nevada Supreme Court vested two parcels of land to Chinese residents where the joss house had stood at Lake and First streets. The joss house, Reno’s oldest Chinese structure, was destroyed by a fire in 1924 but was reconstructed in 1926. It fell into disrepair and in 1958, city officials demolished it but the facade was saved and moved to Gold Hill to serve as a reminder of the area’s Chinese contribution. The final remnant of Reno’s Chinatown on Lake Street, Bill Fong’s New China Club, disappeared in the 1970s as Harrah’s expanded to build a larger parking garage.

N evada Historical Marker No. 29 located in Sparks, dedicated in 1964, celebrates Nevada’s centennial and salutes the contributions of Chinese pioneers with the final sentence, “Their contributions to the progress of the state in its first century will forever be remembered by all Nevadans.”

evada Historical Marker No. 29 located in Sparks, dedicated in 1964, celebrates Nevada’s centennial and salutes the contributions of Chinese pioneers with the final sentence, “Their contributions to the progress of the state in its first century will forever be remembered by all Nevadans.”

A Chinese Pagoda Pavilion was built in Reno’s Rancho San Rafael Park in 1984. Several notable members of the Chinese community promoted its construction, including Lai King Chew (of the Cosmo Club), and Henry Yup (of the Sun Café). Chew was an officer of the Reno Joss House Society when it disbanded, and its remaining treasury funded the pavilion’s construction. These markers serve as reminders of the Chinese culture that became an integral part of the Truckee Meadows today. Surviving the trials and tribulation of the Progressive Era, the Chinese who came to Nevada made their mark on the state’s history, despite the attitudes of the time.