Langston Hughes Sought Solitude in Reno

January – February 2019

Escaping to The Biggest Little City proved prolific for the venerable author.

BY ALEX ALBRIGHT

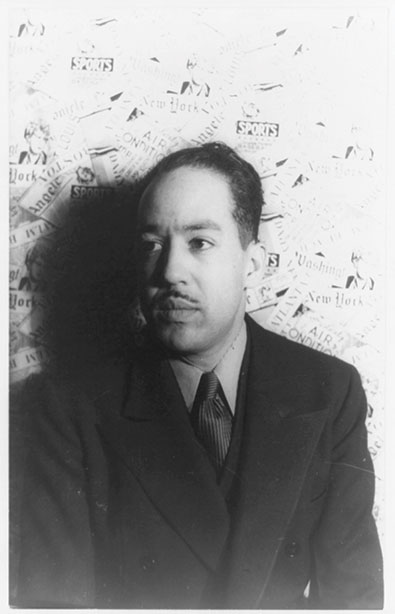

When Langston Hughes caught the 5:55 a.m. train from Truckee, California, to Reno in September 1934, he was 10 years into a career that would be marked by greatness and controversy. Already a successful poet, novelist, and journalist at the age of 32, Hughes was widely regarded as the unofficial poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, which in the 1920s ushered in a prolific and important time for African-American authors, artists, and musicians.

He published more than 35 books—including the popular “Simple” series—11 plays, and an almost countless number of poems and prose in his lifetime. He drew ire from other African-American authors, poets, and critics for his portrayal of black life, which he wrote about in unflinching terms and refused to sugar-coat for a mass audience. Despite the naysayers, Hughes was beloved by the people whose frequently rough lives he wrote about, and he became the first black American to earn a living just from his writing and public speaking.

By the time he stepped off the train in Reno, he had become the most recognizable and controversial African-American writer of his time.

RENO PROVES A MUSE

“I had always wanted to see Reno,” he writes.

He told hardly anyone where he had gone, “to find a little peace and quiet for work.” His time in Reno is overlooked in many accounts of his life.

His first trip to Reno was to scout for a place he might return to for a period of extended and uninterrupted writing that would take him into 1935. He liked what he found in Reno’s Chinese and African-American communities, and in the boarding house where he registered as James Hughes. He returned in early October for what he hoped would be several months of productive, moneymaking writing. However, his father’s death would draw him away from Reno before the end of November.

Hughes had been staying in California, but his active social life was too distracting and his political activities had become dangerous. In Reno, he would live in isolation, and once there he settled quickly into a working routine: 11 short stories were written partially or wholly in Reno or inspired by his time there. Two of his best and most lucrative stories, “On the Road“ and “Slice ’em Down,” borrow heavily from Depression-era Reno for characters and settings.

Hughes’ total time in Reno consisted of the nine-day scouting visit and a subsequent five-week stay at 521 Elko Street. He paid $2.50 a week and lived in the boarding house home of a widow, Helen Hubbard, whose husband had been among the founders of the Reno NAACP in 1919. Hughes recounted later he liked her “big white house with a lawn,” where “everyone puts in a small sum for food and one of them cooks, so it makes eating very cheap. “

THE DRIVE FOR SOLITUDE

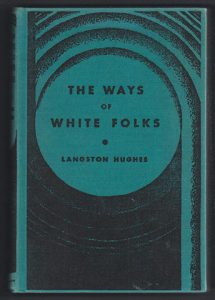

In August 1933, Hughes had accepted a long-standing invitation from wealthy arts patron and social activist Noel Sullivan to stay at his Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, cottage. An ardent admirer of Hughes, Sullivan provided him with everything he needed for a year so that he could “consolidate his career as a professional writer.” By December 1933, he had completed his first collection of short stories, “The Ways of White Folks.”

In August 1933, Hughes had accepted a long-standing invitation from wealthy arts patron and social activist Noel Sullivan to stay at his Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, cottage. An ardent admirer of Hughes, Sullivan provided him with everything he needed for a year so that he could “consolidate his career as a professional writer.” By December 1933, he had completed his first collection of short stories, “The Ways of White Folks.”

Hughes was popular and admired by Carmel’s liberal arts and leftist crowd of affluent whites that included the poet Robinson Jeffers and the socialist Lincoln Steffens. Hughes had become, biographer Arnold Rampersad writes, “the

most glamorous black leader sympathetic to the leftist cause.” But by spring 1934, Hughes was complaining: “there are too many people in my life.” Although his literary output decreased, Hughes remained active both in local politics and in the California labor strife and violence that in 1934 mirrored problems throughout the United States.

After two strikers were killed in San Francisco in July 1934, the Carmel town council ordered tear gas “in order to be ready for civil insurrection;” a group of citizens backed by the newly formed American Legion and “armed with riot guns began to drill on the local polo grounds.” The Carmel “Sun” warned: “There is trouble in store for those who persist in communistic activity, and that is as it should be.” Hughes was warned that he himself was in physical danger and he left Carmel quickly, “not wishing to be tarred and feathered.”

FINDING PEACE IN A TIME OF UNREST

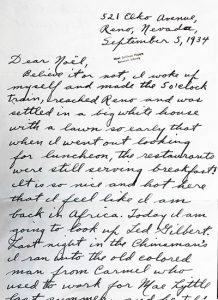

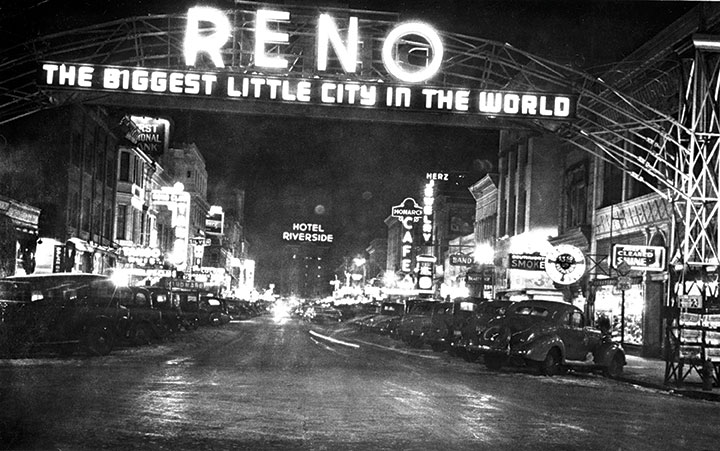

Reno became the writing retreat and safe haven Hughes needed. He describes his arrival in a letter to Sullivan: It was “so early that when I went out looking for luncheon, the restaurants were still serving breakfast! It is so nice and hot here that I feel like I am back in Africa.” He won his first $2 at a casino known as “the Chinaman’s” that evening.

Reno, he writes, was “a very prejudiced town with no public places where Negroes could eat other than two cheap Chinese restaurants.” It had, he continued, “no Negro section as such,” except for a “scrubby little area across the railroad tracks where the Colored Club for gambling was located.”

Afternoon walks introduced Hughes to what he called a large hobo jungle populated by “hungry Negroes from the East” who came through “in freight cars, heading for San Francisco” or “from the Coast, heading for Kansas City or Chicago where they thought times might be better. A few of these black wanderers settled for a while in Reno.” Two of those he met became the central characters of the short story “Slice ’em Down,” which was published in “Esquire” magazine. In “On the Road,” Sarge—another itinerant—seeking sanctuary from a Reno snowstorm, thinks he has pulled down a church with its locked doors, a la the biblical Sampson, though in fact he’s actually been dreaming while being beaten and jailed for vagrancy.

A DIFFICULT TIME

African Americans had been wandering into Nevada since before it became a state, settling first in Virginia City and subsequently in Goldfield, Carson City, and Reno. Race prejudice was nothing new although it was inconsistent, depending on when, where, and what ethnic group was involved. Nevada historian Mella Harmon writes that Nevada’s black population “decreased markedly” during the last decade of the nineteenth century because of the decline in mining opportunities for blacks, and that the state practiced “non-legislated segregation.” But Reno’s black population stayed virtually the same: U.S. Census figures list 22 blacks in 1870, 23 in 1890, and 28 in 1900.

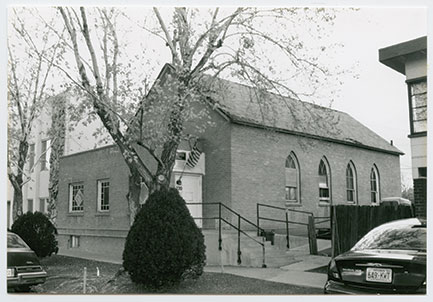

As the economy shifted from mining to vice, Reno became an even more popular stopping-off place, especially for transients hoping for some luck. By 1907, Reno’s permanent black population had grown, unofficially, to 225 and as it was organizing that year, Bethel AME Church anticipated a membership of about 50. One of the city’s new residents that year was the only black weatherman in the U.S., Oscar H. Hammonds. The 1910 census indicates that Reno’s black population had, since 1900, outpaced in growth the white population by over 300 percent.

By the 1920s, the national edition of the Chicago “Defender” had become the most important black audience newspaper in the country, in part because of its weekly reports from communities in every state. Sporadic reports from Nevada began in 1910, but not until 1922 do they appear with any regularity. They reveal an active social and civic life for Reno’s African-American community centered around Bethel AME. Often, these reports take the form of society notes, filled with names of who’s been to what party. They also offer intriguing glimpses into local history: by 1923 the Hubbards were operating a boarding house. They, the Hammondses, and others frequently enjoyed parties that included luncheons, “elaborate buffets,” and “dancing till wee hours.” The Hammonds family was especially active in Bethel organizations and community events. Oscar Hammonds was choir director, leader of a male quartet, and president of the Booker T. Washington Forum.

Hammonds became the subject of the profile by Hughes for the Pittsburgh “Courier” that was reprinted in black-audience newspapers across the country. Born and educated in Indiana, Hammonds began work as a weather observer and was assigned to Reno in 1907, becoming the only black weatherman in the U.S. After a brief posting in San Francisco, he returned in 1910 to Reno and retired from the weather service there in 1935. By the time Hughes caught up with him, he was one of the most influential and popular black citizens of Reno and likely Nevada’s most prolific black author. He wrote monthly weather summaries for the state’s newspapers, which generally printed them unattributed.

Hughes describes Hammonds as a man who enjoyed his work because “it cannot become monotonous as no two days have ever been known to be exactly alike, nor any summer or winter like the preceding summers or winters.”

Revealing his interest in folklore, Hughes asked Hammonds whether science has made folk ways of weather predicting obsolete: “Mr. Hammonds laughed and said, ‘That’s rheumatism, not rain’ and he went on to assure me that amateur weather prophets were much less accurate than charted government observations.”

RENO’S INFLUENCE

In addition to his stories and the Hammonds profile, Hughes wrote about Reno in a memoir, an essay fragment, and several letters; he also kept notes on some of his daily activities.

Under the pseudonym David Boatman he wrote four still-unpublished “white” stories, as he termed them to his agent, not about black life, “but about love.” They were intended to make good money with publication in popular mainstream magazines. The first of these came to him after a sunset walk to a “forlorn little mountain cemetery” outside of Reno, where he had a psychic experience he would later write was a premonition about his father’s death.

While in Reno, he made much of the city and region’s attractions: he kept time for boxer Kid Chocolate who was preparing for a fight at the local Chestnut Street Arena; traveled to Carson City with a singing group, and to Virginia City to see the gold mines and opera house; picnicked at Pyramid Lake; saw “The Count of Monte Cristo” at the Majestic Theatre; won and lost small amounts of money; wandered the streets and out into the hobo jungles on the outskirts of town; and enjoyed “swell blues and jazz” at the local “colored club.”

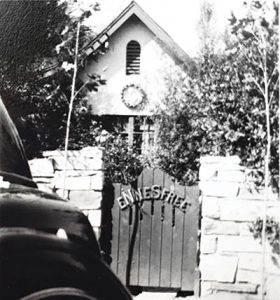

Today, the boarding house in which Hughes stayed is long gone, as are the alleyway joints he frequented. Hillside Cemetery—located near the University of Nevada, Reno—which inspired his story “Mailbox for the Dead” is derelict and endangered by encroaching development. The only significant building still standing is the old Bethel AME Church at 226 Bell Street. The congregation moved to a new building in Sparks in 1993.

After Hughes left Reno, he lived primarily in New York City for the rest of his life. He continued to travel the U.S. and the world, and remained a prolific writer and political activist until his death in 1967.