Odyssey Of A Ghost Town Explorer Part 4

July – August 2016

ODYSSEY OF A GHOST TOWN EXPLORER

FOURTH OF SIX-PART SERIES EXAMINES ABANDONED SETTLEMENTS OFF THE LONELIEST ROAD IN AMERICA.

PART 4: THE ELK OF EBERHARDT

BY ERIC CACHINERO

I am of the deeply held belief that Rocky Mountain elk are among the most majestic and genuine creatures to walk the earth. I am also of the belief that words like majestic and genuine can be used to describe the remains of a place that once quaked with life, but is now presumed to be devoid of it. Ghost towns and elk are each worthy of these words singularly, but when you combine the two, it’s permissible to be at a complete loss for words. I have come to realize that some situations are almost impervious to words, for fear of the word’s inadequacies to describe them.

Though difficult as it may be, I will do my best to describe coming around a bend to find three bull elk standing in the ghost town of Eberhardt. More on that to come.

HAMILTON

The trip begins like many others: historic hotel, the threat of rain and snow, and miles of pure Nevada. In this case, our early, westerly departure from Hotel Nevada in Ely gives us what we hope will be enough time to visit a cluster of tightly packed ghost towns located south of U.S. Route 50 near the White Pine Range and mighty Mt. Hamilton. Mule deer and panoramas are prevalent while driving the dirt road leading to Hamilton. Editor Megg Mueller and I stop first at Hamilton’s aging graveyard, then at the town’s relatively scant remains.

The trip begins like many others: historic hotel, the threat of rain and snow, and miles of pure Nevada. In this case, our early, westerly departure from Hotel Nevada in Ely gives us what we hope will be enough time to visit a cluster of tightly packed ghost towns located south of U.S. Route 50 near the White Pine Range and mighty Mt. Hamilton. Mule deer and panoramas are prevalent while driving the dirt road leading to Hamilton. Editor Megg Mueller and I stop first at Hamilton’s aging graveyard, then at the town’s relatively scant remains.

It’s surprising they’re limited, given Hamilton’s size in the 1800s. Silver discoveries and the lure of swift wealth were as enslaving as opium in 1867 Hamilton. Fittingly, the first business established was a saloon, followed by more than 10,000 miners and townsfolk, some living in nothing more than caves, tents, and huts made of hay. By 1869, Hamilton had grown significantly, welcoming a slew of general stores, churches, banks, breweries, gunsmiths, and approximately 195 mining companies to the two-square-mile townsite. But seemingly as quickly as the town had sprung from the ground, it succumbed to diminished riches and devastating fires that tapered the population through the 1920s and into eventual nothingness.

Modern buildings interspersed with ghostly ones are most of what’s left. A large, stone chimney keeps watch over the town, while evidence of mining can be seen in most directions. Megg and I explore the ruins before taking a short, scenic drive down the road to our next town.

EBERHARDT

Megg sees them first. Our Tahoe comes to an abrupt halt before the on-board chaos begins. Megg is trying—albeit failing—to gasp the three-letter word “elk” while slapping my arm and reaching for her camera. My brain is in the same state of discombobulation, though I opt instead for my binoculars. I’ve seen plenty of elk in my life, but never in a scene such as this. The three small bulls model long enough for Megg to get their glamor shot, then, as elk tend to do, hightail it without looking back.

Eberhardt is used to riches. Named after the largest mine in the area, Eberhardt’s prospectors were said to have a certain glow to them—literally. The Eberhardt mine had ceilings and walls made of glittering silver, transferring a fine coating to the boots and clothes of the men who worked in it. From 1869 to 1880, the town and area were worked, until the mines closed and Eberhardt returned to the elk.

Though these sites were briefly threatened by man’s attempt to wrangle them in, Mother Nature always returns for what’s rightfully hers. So have the elk reclaimed what’s theirs. We linger a while to take photos before moving on, feeling guilty for interrupting the elk’s Eberhardt city council meeting, or whatever they were doing there.

SHERMANTOWN

If I were an 8-foot-tall man, I would have trouble navigating Shermantown in its current state. Located just a couple miles from Eberhardt, the town is being consumed by the tallest sagebrush I’ve ever encountered, which gives it a maze-like atmosphere. Skeletons of sandstone buildings poke out amid the foliage, evidence that the shrubbery was once better confined.

It’s no surprise Shermantown’s sagebrush grows so tall. Water and wood supplies were abundant during the town’s—then called Silver Springs—roots in the 1860s. Eight mills, four furnaces, and two sawmills sprung up with Shermantown, as did nearly 3,000 residents. The town’s canyon location made it one of the most desired camps in the White Pine mining region because it sheltered residents from the elements. The year 1870 saw the end of Shermantown, save a lone family that is said to have resided there for another decade.

A decaying chimney structure, along with roofless buildings full of bullet holes, keep Megg and me occupied. Fresh springs dot the hills around the townsite, as does an abundance of pine trees. We retrace our steps in an attempt to reach the last ghostly structure of the day.

BELMONT MILL

We’re not running out of precious daylight yet, but we’re getting close. And what better way to save some of it than taking a shortcut? Yea, right.

We’re not running out of precious daylight yet, but we’re getting close. And what better way to save some of it than taking a shortcut? Yea, right.

It is somewhere between inching down a less-than desirable (putting it lightly) road with a tapering cliff on one side and realizing we have absolutely no clue if we’re even on the right road that my absolute admiration for the pioneers of the past kicks in. They traveled these roads with horses, wagons, and on foot, carrying hundreds of pounds of supplies. Our air-conditioned, four-wheel drive SUV makes us look like amateurs. I know I can hear deer snickering at us from behind the sagebrush.

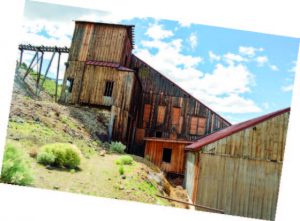

After traveling an hour out of our way and ending up back at the same exact point we had started, we decided to nix the shortcut and take the logical, but longer road to Belmont Mill. We reach the mill with a little bit of daylight to spare, and to my amazement, it’s one of the largest abandoned structures I’ve ever seen in Nevada.

The Tonopah Belmont Development Company built the mill in the mid 1920s, and allegedly constructed it using machinery and parts salvaged from the company’s operations in Tonopah and Goldfield. According to an article by the Nevada Appeal, “Records indicate that despite the considerable investment—Belmont Mill was set up as a company town—the mines proved to be marginal and the camp was abandoned after about a decade of mining.”

The mill speaks for itself. It’s incredible to sit back and absorb the intricacies of this building, just imagining the sounds and smells that must have perforated the air during its operation.

Please look but don’t touch the mill, and do not enter the building. Though standing, floorboards and beams are decaying and present a dangerous situation.

As the sun sets, Megg and I hightail it to the quaint Union Street Lodging Bed and Breakfast in Austin for some shuteye.

BERLIN

Well-rested and with French toast and rocket fuel in our bellies, Megg and I set off for our final ghost town of the trip: Berlin. We, of course, take the backroads through the Reese River Valley and Ione. I believe this is the first time this year on a ghost town trip that weather and roads are cooperating with us fully.

Berlin is what most ghost towns would look like if they were protected from weather and vandals and survived the test of time. Located in Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Berlin is well preserved. According to Nevada State Parks, Berlin is “maintained in a state of ‘arrested decay.'” The park office, ranger residence, and maintence shop are all housed in historic cabins.

In 1863, a man named A.J. McGee discovered silver near Berlin, sparking the creation of the Union Mining District, which included Union, Grantsville, Ione, and Berlin. Major silver in Berlin wasn’t long lasting, but in 1900, the Nevada Company built a 30-stamp mill, which still exists and is in fantastic shape. By 1907, the mines began to play out after producing $849,000 in silver.

SPECTACLES

The more I travel this state in search of places that supposedly used to contain life, the more I learn that they are, in fact, still full of it. Ghost towns are some of the liveliest places in existence.

Sure they don’t have honking horns, sirens, and people; you have to look much deeper than that. Wide-open spaces give your soul the vital room it needs to sprint full speed in every direction, and to appreciate what it truly means to see, touch, and experience nature. Ghost towns may be the destination, but they certainly act as only a fraction of what you gain from visiting them. And don’t forget the elk. There are those, too.