Yesterday: Potosi Mine

July – August 2019

BY ELIZABETH HARRINGTON

BY ELIZABETH HARRINGTON

This story originally ran in the Summer 1968 issue of Nevada Magazine.

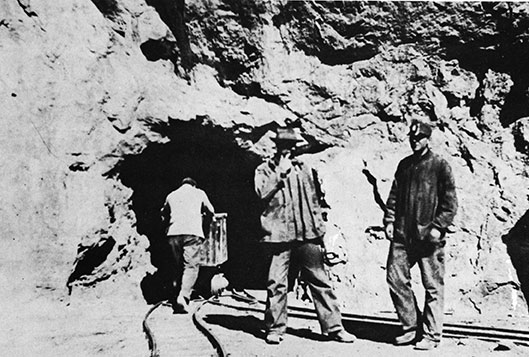

High up in the mountain, 35 miles southwest of Las Vegas, is found one of the places most significant to Nevada’s early history. This is the old Potosi Mine, the first lode mine ever worked in the state. Located near 8,504-foot Potosi Mountain, south of Las Vegas off the highway to Pahrump, the old mine is but a short distance from the historic Old Spanish Trail. An unpaved dirt road leads to Potosi and to travel over it a Jeep or pickup truck is advised.

History does not reveal exactly when Potosi was discovered. Most historians are loathe to commit themselves definitely when discussing the early history of southern Nevada—wisely so, because no maps or records of the Spanish period are known to exist. Many will speculate, however, and say that it is possible and even probable that a group of Spanish missionaries, the Franciscans, with a group of Mexican peons, sailed from Mexico up the Colorado River in 1776 as far as the big bend, near the present site of the Hoover Dam, with the idea of teaching Christianity to the Indians and exploring the land and seeking wealth in the mountains. Then, proceeding from this assumption, we can believe that the padres explored the area, looking for silver and turquoise. They opened silver mines, the workings of which are said to still be in evidence, and they eventually left the area for reasons we can not know. Substantiating the theory that the Spanish were here in 1776 are the lingering stories, mostly handed down by such Las Vegas old timers as the late Helen Stewart, that coins and religious articles of the period have been found in the area. A rosary, for example, is supposed to have turned up in one of the old abandoned mines and attached to it, coins from the Island of Luzon from which the padres had sailed in 1767.

The first known trail near Potosi was blazed in 1829 by Rafael Rivera, chief scout and guide for the historic Armijo Party that was sent out by Jose Antonio Chavez, Governor of New Mexico, to determine the shortest route between Santa Fe and California for the trading caravan of the day. The old Escalante Trail to Southern Utah had earlier been established. The Armijo Party now had to bridge the gap between Southern Nevada and California. Rivera scouted the mountain and the entire area around Potosi, and the route finally taken by Armijo was that which became the Old Spanish Trail.

The modern recorded history of Potosi began in 1855 when the Mormon Church sent colonists into what they thought was a part of Southern Utah, to start a farming community. (Actually, at the time the area that is now Southern Nevada belonged to the New Mexican Territory and, later, to Arizona Territory.) Four years earlier, in 1851, the Mormons had started another settlement at San Bernardino and it was while some of the colonists were traveling over the mountain from Las Vegas to the growing town that they came upon Potosi. After exploring the mine and finding it rich with lead and other metals, the nature of which they could not determine, they lost no time sending word to Brigham Young about the find. Lead was then badly needed by the Mormons for making bullets, so Young immediately dispatched an experienced mining man, Nathaniel V. Jones, to take charge. Probably it was Jones who gave the mine its name—after the Potosi district in southwest Wisconsin where he had lived as a young man. Th Mormons proceeded to dig a well near a running spring and to build a number of log cabins in the three-mile ravine below the mine. They first tried to smelt the ore at the mine, using pitch and cedar wood for fuel, but because the water supply proved inadequate, they decided to haul the ore down to Las Vegas where springs were in abundance.

Authorities differ on the subject, but it seems fairly clear from the journals they wrote in Las Vegas that the Mormons now built a small smelter inside the walls of the Las Vegas stockade and successfully recovered lead which they sent back to Utah. This, then, was the first smelter west of the Missouri and the first to ever operate in Nevada.

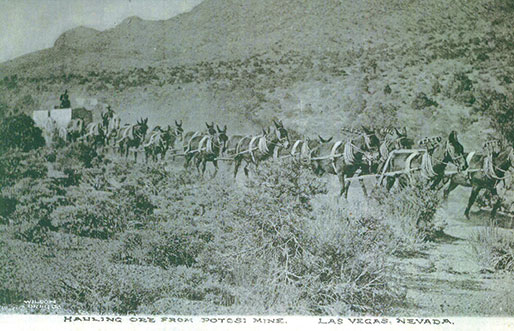

Oxen and burros—mainly the latter—were pressed into service to haul the ore, and evidently some of the burros wandered off or were released to go wild. At least numbers of these lowly animals still roamed the hills around Potosi as late as 1919.

Oxen and burros—mainly the latter—were pressed into service to haul the ore, and evidently some of the burros wandered off or were released to go wild. At least numbers of these lowly animals still roamed the hills around Potosi as late as 1919.

Packing ore down over the mountains was a slow, tiresome task for the heavily-laden animals but the Mormons fortunately were able to establish a rest stop on a level spot part way down where there was running water. Here they set up a camp that thereafter was always known as the Old Mormon Camp.

After two years working the mine, during which time they founded a thriving farming community at Las Vegas, Brigham young suddenly ordered the Mormons to return to Salt Lake because of serious trouble between the Federal Government and the Mormon Church, and on Feb. 2, 1857, the colonists left Las Vegas and the mine—and thereby Potosi became the first ghost town in Nevada.

Following the departure of the Mormons, mining activities at Potosi continued sporadically for the next 40 years. According to existing records several large firms, such as the Silver State Mining Company in the seventies, were active during the period. However, much of the development at Potosi and nearby claims was performed by prospectors working on their own.

After the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad (now the Union Pacific) was built through southern Nevada in 1905, new assays of the complex ore were made and when it turned out that, in addition to its rick lead and silver deposits, the ore also contained a large zinc content, Potosi was reactivated. The Yellow Pine railroad outlet was established om 1910, a smelter built at nearby Goodsprings, and Potosi then became one of the major producers of zinc, a metal in great demand throughout the country.

Next to exploit this rich zinc deposit was a large company, The Empire Zinc Company of New Jersey, with main offices in Denver, Colorado, which took over the mine in 1913. Here in the ravine where the Mormons had built their log cabins 58 years earlier, the Empire Zinc company built an attractive little camp with comfortable houses and other necessary buildings all of a uniform gray. The company installed an electrical plan and built a calciner near the mine. An excellent road was constructed and maintained from Potosi to Arden, over which the ore was hauled in large trucks to the railroad, there to be shipped all over the country.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Potosi was classified as a priority defense project, producing badly needed zin, silver, and lead. As level after level was worked and hollowed out, the old mine literally gave her all toward the war effort.

Besides all the war activity, the summer of 1918 was a productive one for the little camp in other ways—as is evident from the following excerpts taken from the “Las Vegas Age” of Aug. 3, 1918:

POPULATION INCREASED AT THE POTOSI MINE

Born—to Mr. and Mrs. Ralph W. Smith, July 27, 1918, at the Potosi Mine in Clark County, Nevada, a daughter, Barbara Jane. Mr. Smith is the Engineer at the mine.

—to Mr. and Mrs. Frank M. Stephens, July 30, 1918, at the Potosi Mine, Clark County, Nevada, a son, William Winchell. Mr. Stephens is the Superintendent of the mine.

—to Mr. and Mrs. Arthur H. Harrington, Aug. 1, 1919, at the Potosi Mine, Clark County, Nevada, a son, Vincent Bailey. Mr. Harrington is the Bookkeeper of the mine.

—The arrival of the three babies at the Potosi camp within five days, and the fact that they are the first babies born at the mine, constitute a remarkable coincidence. “The Age” is happy to extend the congratulations of the country to all concerned.

After the armistice was signed in 1918, the Empire Zinc Company began cutting forces rapidly as it was evident that it could continue working the old mine on a large scale. By late spring of 1919, the large force of men had dwindled to only a few. The office force was also reduced. Ralph Smith, the engineer, was the first to go. He was sent to the main office in Denver. Next to be transferred was the superintendent, Frank Stephens. The foreman of the mine, Samuel Rowe, left to make his home in Long Beach, California.

The only remaining member of the office force was the bookkeeper, Arthur Harrington. The Empire Zinc Company placed Mr. Harrington in full charge of supervising the dismantling of Postosi. By fall the mine was completely shut down and dismantling was in full progress. The equipment was shipped to other mines belonging to the Empire Zinc Company and the buildings were sold. Some were dismantled and reassembled in Las Vegas.

After the Empire Zinc Company abandoned Potosi, it was leased by A.J. and A. R. Robbins of Goodsprings. In 1925 the old mine produced 31,000 tons of zinc. Hearing of this huge output, the International Smelting Company sent engineers to look over the property in 1926. The assays made at this time showed much promise and the company leased the mine for two years. But again it proved too expensive to operate and Potosi was abandoned after a few months.

And so this old mine, after yielding fortunes in silver, lead, and zinc, and after enriching Nevada and the entire nation so handsomely, at last stand retired and deserted. But surely, having played a part for so many years in western history, Potosi is indeed worthy of honor in Nevada’s pioneering past.