St. Augustine’s Cultural Center

March – April 2015

St. Augustine’s Cultural Center

AUSTIN CHURCH GETS A SERIOUS MAKEOVER.

STORY & PHOTOS BY ERIC CACHINERO

On Christmas Eve 1866, St. Augustine’s Catholic Church in Austin was officially dedicated. The bricks and solid-granite foundation used in its construction were pulled from the Austin quarry and brickyard, which flourished in the 1800s. The church was constructed primarily by volunteer labor from Austin’s Irish-Catholic community at a cost of $50,000—an enormous sum of money in 1866—and designed to look like a ship sailing out to sea. Though an impressive feat of Gothic Revival and Italianate architecture, the sting of senescence began to take hold on a building nearly as old as the state itself, and it eventually fell into disrepair. This was, however, until one woman—along with the help of many others dedicated to preserving this piece of Nevada history—took over and the church received a restoration and a whole lot of tender loving care.

A LOT OF ELBOW GREASE

That woman is Jan Morrison, a retired developer from Las Vegas. After purchasing, renovating, and moving into a small cottage near St. Augustine’s in 2003, she says the church, which had become overgrown with weeds and debris, literally kept her up at night.

“Metal panels from the roof were beginning to come loose, and the creaking would keep me awake,” Jan says. After discussing the weathered structure with a fellow resident, a subtle challenge was offered: “Well then, why don’t you buy it?”

“One thing led to another, and a year and a half later I had purchased it,” Jan adds.

Jan then submitted her first grant application, which allowed preservation historian Dan Pezzoni to study the church and prepare a historical analysis and blueprint for the restoration. Dan also authored the original report to the National Register of Historic Places, which resulted in St. Augustine’s being added to the list. “The grant was awarded by the Nevada Commission for Cultural Affairs, and I was on my way to 10 years, 9 grants, and over a million dollars spent on the restoration,” Jan says.

The dream was becoming a reality.

Over the span of a decade, the church received a serious facelift. Windows, doors, a meeting room, bathrooms, catering kitchen, and an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant lift—which operates between the lower and upper levels of the church—were among the many additions. The entire roof was also reconstructed just in the nick of time, as it was on the brink of collapse.

The blood, sweat, and tears paid off, though, all leading to the apex of the renovation—the rededication of the church.

REDEDICATION: CATHOLIC CHURCH TO CULTURAL CENTER

On Sept. 27, 2014, the once-tattered church was rededicated, now under the name St. Augustine’s Cultural Center. According to Jan, the event drew people from far and wide, sharing stories of the church and discovering common threads of shared history.

“We sold some of the architectural salvage from the restoration,” Jan says. “Many people took home doors, kneelers, pews, and wonderful hand-hewn planks.” Several of these pieces of history are still available for purchase.

The highlight of the evening was the playing of the church’s Henry Kilgen Nine Rank pipe organ. The cultural center was bathed in the golden glow of the Austin sunset when pipe organ historian Michael Friesen brought the instrument to life publicly for the first time in more than 40 years. “I don’t think anyone took a breath during the first selection,” Jan adds.

NO ORDINARY ORGAN

A member of the well-known Kilgen organ-building family of St. Louis, Mo., Henry Kilgen built the organ that resides in St. Augustine’s today in 1884. Although it is uncertain how many organs he built during his lifetime, only six have been documented. The Nine Rank pipe organ in Austin is the only known surviving organ constructed by Henry Kilgen that is tonally, mechanically, and visually intact.

An article in the Reese River Reveille newspaper dated Sept. 15, 1884, gives an account of the organ’s debut in the church: “Yesterday morning the new Catholic organ was initiated, so to speak, into its work of producing melodies for the religious services of that society, by the rendering of Haydn’s master piece [sic]—the Second Mass.”

In May 2012, the approximately 3,000 pieces of organ were carefully dismantled; shipped to Conifer, Colo.; and restored by pipe organ builder Charles Ruggles. After removing layers of dust, bird droppings, and bat guano—and straightening out some of the interior pipework said to be damaged by a cat snacking on the critters that lived inside—the organ was reassembled. Once assembled in Colorado and tested for playability, it was once again disassembled, shipped back to Austin, and then reassembled where it remains today.

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

Although the cultural center has been rededicated, there are still several upcoming projects, including a sound-and-light system for performances. The cultural center will eventually house an arts center, offering space for artist workshops, historic presentations and dramas, docent tours, local art shows, music presentations, and exhibits of Austin and central Nevada. The center is also able to host events from business meetings to family reunions. According to Jan, the large meeting room can hold 40-50 people, whereas the upper level can seat approximately 150. Jan says they also have plans for a ‘fiddler’s weekend,’ which will feature old-time music. Though there is not a finalized schedule of events, check out goaustinnevada.com/staug.html as information is constantly updated.

Looking Back: Women who led the way

Female political pioneers made history and policy.

Female political pioneers made history and policy.

BY NEVADA MAGAZINE

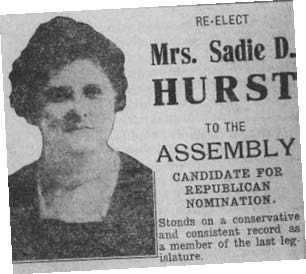

The 78th session of the Nevada Legislature began Feb. 2, and when the 63 members of the Senate and Assembly met, Nevada’s 21 female legislators took their seats. Women first voted in Nevada in 1916, and in 1918, Sadie Hurst made history as the Assembly’s first female. Since then, Nevada has had at least one woman representative each session, with just four exceptions: 1917, 1931, 1933, and 1947.

Twenty years ago in our March/April 1995 issue, we took a look at two political pioneers: Hurst and Frances Friedhoff. These women came forth in a time when women were likely considered to be mothers and homemakers, and then citizens. Their voices, while small compared to their peers, made a difference on the role of women in Nevada. You can find the full story on our website, but take a look at this condensed version of the story we ran 20 years ago.

Leading Ladies of Nevada’s Legislature

Lawmakers Sadie Hurst and Frances Friedhoff led the way in changing the all-male club of the Nevada Legislature.

BY DANA R. BENNETT

On Election Day in 1918 the Nevada State Journal took an unusual stand: The newspaper endorsed a female candidate for the state Assembly. No woman had ever served in the Nevada Legislature. In fact, women did not vote in state elections until 1916.

Nevertheless, the Reno paper reminded its readers that Republican candidate Sadie Dotson Hurst “has taken an active part in public matters” and assured them that her experience in club work “will stand her and the people of Nevada in good stead should she be elected to the assembly.” Washoe County voters apparently agreed, electing Hurst as one of their seven representatives for the 1919 session in Carson City. Hurst thus became the first woman elected to the Nevada Legislature and a trailblazer for women like Frances Friedhoff, who became Nevada’s first female state senator in 1935.

Although their terms were brief, Hurst and Friedhoff opened important political doors for women in the Silver State.

Hurst’s election in 1918 reflected the growing political presence of women in America. In Nevada, women were involved with the legislature from the beginning. Hannah K. Clapp of Carson City lobbied the Territorial Legislature (1861-1864) to improve education. In 1877, Mary E. Wright of Virginia City became the first female legislative clerk. But it wasn’t until November 1914, following a hard-fought, 45-year battle in the legislature, that Nevada women won the right to vote in state elections.

Sadie Hurst, like many other Nevada politicians, was part of the social reform movement known as Progressivism, which was then sweeping the country. Although details of her early life are sketchy, it is known that Hurst was born in Iowa in 1857 and moved to Reno with her two sons after the death of her husband. In Reno, she became involved in women’s civic clubs and community improvement projects, both Progressive hallmarks.

Her preoccupation, however, was another Progressive proposal—Prohibition. Unlike ax-wielding Carry Nation, famous for literally breaking up Kansas bars, Hurst used political persuasion to stop the sale and consumption of alcohol. In those days Reno was the epitome of the Wild West, a center for easy divorces, championship prize fights, and back-alley card games. But the public’s interest in moral reform and concern about supplies during World War I (grain was better used for food than booze, ran one argument) were strong during the 1918 election. Remarkably, Reno voters elected an entirely “dry” delegation, including Hurst, to the legislature.

Early in the 1919 session the Nevada State Journal remarked that “the woman lawmaker, Mrs. Hurst, has already had the pleasure of seeing some of her legislative propositions take the form of law.” In one of its first actions, the legislature, meeting in its chambers on the second floor of the State Capitol, endorsed the Prohibition amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The paper also noted that “Mrs. Hurst’s petition to Congress for woman’s suffrage” had passed.

The presence of this new Assembly member occasionally mystified the formerly all-male body. “Much discussion goes on in the assembly as to how to address the Hon. Sadie Hurst,” the Journal reported. “Some call her the assembly woman while others salute her as the ‘gentle lady.’ “Whatever they called her, the paper stated that “the Washoe delegates are very proud of having a woman delegate.”

Chivalry, however, did not stop the male legislators from making fun of Hurst’s legislation or excluding her from functions. After she introduced a bill prohibiting cruelty to animals, some legislators arranged a street fight between a badger and a bulldog. Outraged, Hurst rose on the floor of the Assembly to protest this brutal plan, only to find herself the butt of a joke when it was revealed that the “badger” in the covered cage was really a chamber pot.

Despite such obstacles, Hurst sponsored several bills involving women’s rights. One would have given a mother control of her children and their estates upon the death of the father. Another would have allowed women to enter into any legal contract. Neither bill passed. A third measure would have required a wife’s signature, in addition to her husband’s, to deed real estate held as community property. The bill passed the Assembly but was tabled in the Senate.

Hurst’s successful bills included one that raised the age of consent from 16 to 18 years and increased the penalties for rape. Her bill outlawing animal cruelty was also approved, despite the badger-fight prank. Both houses passed Hurst’s measure requiring the registration of nurses. Although Nevada was then the only state not regulating the nursing profession, Governor Emmet Boyle vetoed the measure because it did not specify standards.

Hurst was clearly not intimidated into silence by being the only woman in the legislature. As an adamant Prohibitionist, she strongly opposed a bill, which passed, allowing the sale of “near beer” and flavored cooking extracts that contained minuscule amounts of alcohol. As a suffragette, she stood up for women’s rights. She also was staunchly conservative, indeed reactionary, on some matters. When the 1919 session considered a bill to legalize marriages between Native Americans and Caucasians, it was Hurst who led the floor fight against it. However, her colleagues were not swayed by her arguments, and the bill passed by a substantial margin.

A year later the legislature met in special session to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted the vote to women nationwide. Hurst and other suffragettes made sure enough legislators would be in Carson City to vote for ratification. When the special session opened on Feb. 7, 1920, animated suffrage supporters filled both chambers.

Hurst ran for reelection in 1920 but was soundly defeated in the Republican primary. She left Reno two years later with her sons. In 1952, Nevada’s pioneering assemblywoman died in Pasadena, Calif, at the age of 94. Hurst opened the doors to the Assembly for women throughout Nevada.

The doors to the Senate, however, were closed tightly against women until 1935. That year Frances Friedhoff of Yerington was appointed to replace her husband, George, who had resigned to take a job with the Federal Housing Administration. She was sworn in as the senator from Lyon County on March 16, 1935. Because the session was nearly over, she sat in the legislature for only 14 days, and her senatorial tenure lasted little more than seven months.

Friedhoff, no stranger to politics, was not simply warming an empty chair. Raised in Carson City, she had worked as a teenager in the household of former Nevada Governor R.K. Colcord. She married George Friedhoff in 1912, and the couple moved to a ranch outside Yerington. She became active in civic affairs and in the state’s Democratic Party. Frances sold Liberty Bonds during World War I, organized the first 4-H club for girls in Mason Valley, and helped establish the Lyon County Farm Bureau. She led the movement to establish a Yerington library and consolidate rural schools. In 1923 she was appointed to the State Vocational Board of Education, on which she served for 20 years. In 1924 she was elected Democratic national committeewoman from Nevada. When George resigned from the State Senate, Frances was a logical choice to take his seat.

The seating of a woman in the Senate was much more interesting to the state’s newspapers than Hurst’s election to the Assembly had been. On March 17, 1935, the Nevada State Journal trumpeted: “The Senate Ceremoniously Greets First Woman Member of Body.”

She chaired the Senate Committee on Public Lands, of which her husband had been a member. In legislation, Friedhoff had a perfect success rate: Her only bill, which granted industrial insurance to Nevada Emergency Relief Administration workers, was passed.

Despite encouragement, Friedhoff declined to run for the seat in 1936. Thirty years would pass before a woman—Helen Herr of Las Vegas—was elected to the Senate.

After Frances Friedhoff died in 1958 at the age of 63, the legislature memorialized her as “an illustrious standard bearer in the front ranks of woman’s battle for political prominence in Nevada.”

Frances Friedhoff and Sadie Hurst are unique among Nevada’s women lawmakers: In their respective houses, they were the first. Today, when women are elected to the State Legislature, newspapers no longer debate their proper titles.

Visit nevadamagazine.com to read the full story as it appeared in 1995.