Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 2

March – April 2016

ODYSSEY OF A GHOST TOWN EXPLORER

SECOND OF SIX-PART SERIES EXAMINES ABANDONED SETTLEMENTS OF SOUTHWESTERN NEVADA.

PART 2: ROAD NOT MAINTAINED IN WINTER

BY ERIC CACHINERO

Sometimes we have the seasons in their regular order, and then again we have winter all the summer, and summer all winter. Consequently, we have never yet come across an almanac that would just exactly fit this latitude. —Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain)

Twain knew what he was talking about. Nevada’s varying climates make it a Rubik’s Cube of weather patterns. With modern technologies, you can walk in the deadly heat of Death Valley one minute and stand in a blizzard near Boundary Peak less than three hours later (a 10,000-foot change in elevation if you climb to the top). Yet even with these technologies, we have no way of controling what conditions will exist in a remote area before arrival.

But that’s all part of the adventure: traveling into parts unknown, with discoveries unknown, sometimes looking for towns you’re not even sure still exist. That’s the enticing thing about ghost towns: even when you find nothing, you still discover something. Just take caution not to let impassible snow banks or flat tires in the desert hinder your sense of discovery. We didn’t.

AURA OF AURORA

The road coughs patchy mud and slush on our windshield after we turn off State Route 338 and start down National Forest Road 028 en route to Aurora. Editor Megg Mueller and I soak up the cool morning aura and the fact that we’re on the clock as the road winds sluggishly by leafless cottonwoods along the east fork of the trickling Walker River. Our 4WD gets us most of the way, but a couple miles before Aurora, the snow gets a bit too deep to continue and we’re forced to walk to our destination.

Nowhere near civilization, and I feel at home more than ever. There’s no denying we’re on a Nevada treasure hunt. After hiking through several “one last bends,” reality sets in and we realize that we’re not making it to the ghost town; or at least if we had in fact made it, most of the site would be covered in deep snow. Besides the presence of a rather large structure near the road, it’s not apparent to me if we’ve made it to Aurora or are simply on the outskirts.

Aurora popped up in the early 1860s after the yellow metal was found in the area. Because of the rich ore and proximity to the California border, in 1861, the California legislature claimed Aurora as the Mono County seat, and the Nevada Territory declared it to be the headquarters of Esmeralda County. The town had two sets of county courts operating for nearly two years until the Nevada Territory was determined to be the rightful owner. Residents and mining profits were sporadic throughout the decades before dying out. The town was eventually semi-leveled due to the post WWII brick market.

Aurora attracted the likes of Samuel Clemens, who briefly called the town home. It is believed that while in Aurora, Clemens sent a series of lively sketches to the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, thus beginning his career as one of the country’s most renowned authors.

After some time hiking through the snow, we scarf a quick lunch and make our way to our next ghost town.

MERRY MARIETTA

Located in the Marietta Wild Burro Range, Marietta’s history is different than many other mining camps in Nevada. That’s because it was not gold and silver they were after, but a combination of different elements all together.

In 1867, the draw was sodium chloride (salt), which was taken to Aurora and Virginia City by pack mule (unconfirmed rumors say via camels) to be processed. In 1872, Francis M. Smith discovered crude borax in the area, and would eventually accept the moniker of “Borax Smith” and become a controlling force in the world borax market.

Marietta became a town in 1877, and quickly acquired mills, saloons, a post office, a population of about 150, and a store owned by Smith, the remnants of which still remain. Borax was shipped to Wadsworth via wagon teams, before it made its way to San Francisco. Marietta’s stone structures and foundations are a pleasure to explore. Though no burros are visible as Megg and I poke around, we can hear pulsing brays in the distance. Our eyes are glued to the soft earth beneath us, analyzing broken bottles, rusted cans, and even gravestones from years past.

SOUTHERN BELLEVILLE

A historical marker off S.R. 360 greets us, practically bleeding Wild West. It tells of Belleville’s notorious days in which it was famous for murders, drunken brawls, prostitution, and practical jokes. At one point, the town contained a schoolhouse, two hotels, restaurants, saloons, and an assay office. By the late 1880s, the town fell to competition from nearby Candelaria, and was deserted by 1892.

Because of a rapidly setting sun and cold temperatures, Megg and I decide to view this ghost town from the road, leaving us enough daylight to reach Candelaria. Several remnants of Belleville’s stone structures dot the landscape, as do mounds of dirt scattered seemingly at random.

CANDELARIA’S CHARM

Up the road several miles we turn on Candelaria Junction, which leads us to the ghost town approximately 6 miles from the pavement. Large scale mining began in the area in 1873, which led to a boom that would produce saloons, a school, three doctors, a lawyer, two breweries, and hotels that were noted for their high-class setting and quality wine and liquors. Though the town seemed to be living the highlife, this was not the case. It is said that relentless sun and dusty conditions contributed to Candelaria becoming one of the toughest camps in the state.

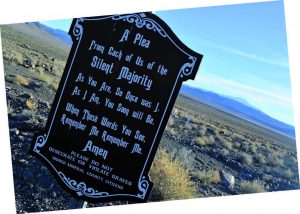

The town has much to explore. Wooden cabins and massive stone foundations show just how large the town once was. As Megg and I explore what we think is an old bank, our suspicion is confirmed by an old safe out back (no gold inside). A graveyard sits towards the east side of town, and contains headstones old and new.

YOU’RE A BEAUTY, BONNIE CLAIRE

After taking a day to explore Beatty and Rhyolite (see page 66), we return to our excursion, with Bonnie Claire in our sights. Located on S.R. 267 just off U.S. Highway 95, the town sees its fair share of traffic, but remains a treasure all the same.

The town suffered quite the identity crisis throughout the years. In the 1880s, gold mining began, and the settlement was known as Thorp, Bonnie Clare (without the i), and briefly Montana Station. Several rail lines ran near the town, including the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad and later the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad. After a mining decline in 1909 in nearby Rhyolite caused weakening railroad traffic, the town began to die out. It experienced a brief revival due to the construction of the Lippincott Smelter in 1953, much of which still remains.

Because of Bonnie Claire’s proximity to a major highway, vandalism and litter have taken a toll on this site. It still is, however, worth a visit. The town consists of several wooden buildings, along with the nearby Lippincott Smelter. Although the smelter is on private property, it can still be enjoyed from a distance.

With a full day ahead of us, Megg and I press north in the direction of the Hard Luck Castle, taking what we think will be a shortcut to Gold Point.

THE HARD LUCK PICKLE

Pop. Hiss. Dead in our tracks.

Tire pressure lights on the dashboard convulse and flash just about the time a sharp rock leaves us temporarily stranded in the desert, miles from the nearest civilization. It’s our first flat tire of 2016, and our second in four months. Luckily we always come well prepared on these trips (food, water, emergency GPS, etc.), and didn’t need to rely on emergency items this time. We get the tire swapped out, and laugh at the ironic turn of events that occurs in the Hard Luck area.

Though it’s a tough decision to make, we choose not to press on, unfortunate because we have a host of ghost towns planned for the rest of the day: Gold Mountain, Oriental, and Sylvania, to name a few. But we know better than to drive deeper still into the desert with no spare tire.

So it’s back out to the highway headed for home. We make a brief stop at Gold Point before we employ Tonopah Brewing Co.’s delicious barbecue to help lift our spirits after an eventful yet slightly disappointing turn of events. I know we’ll visit the ghost towns we missed some day. Hopefully the ghost towns of spring will bring us dry roads and not such hard luck.