Yesterday: The Arrowhead Man

March – April 2020

Fallon man walked with a keen eye for yet another find so that the past would not be lost to the present…or to the future.

STORY AND PHOTOS BY BRENDAN WESLEY

This story first appeared in the No. 2 1976 issue of Nevada Magazine

Nevada law forbids excavation or exploration of historic and prehistoric sites without a permit. Nevada Revised Statutes 381.195-227.

George Luke figures he was about 12 years old when he first spotted an Indian arrowhead poking out of the Nevada soil. That was in 1911, near Reno. “I’ve been hunting them ever since,” says the retired cattleman, now 77 years old. “I still go out!”

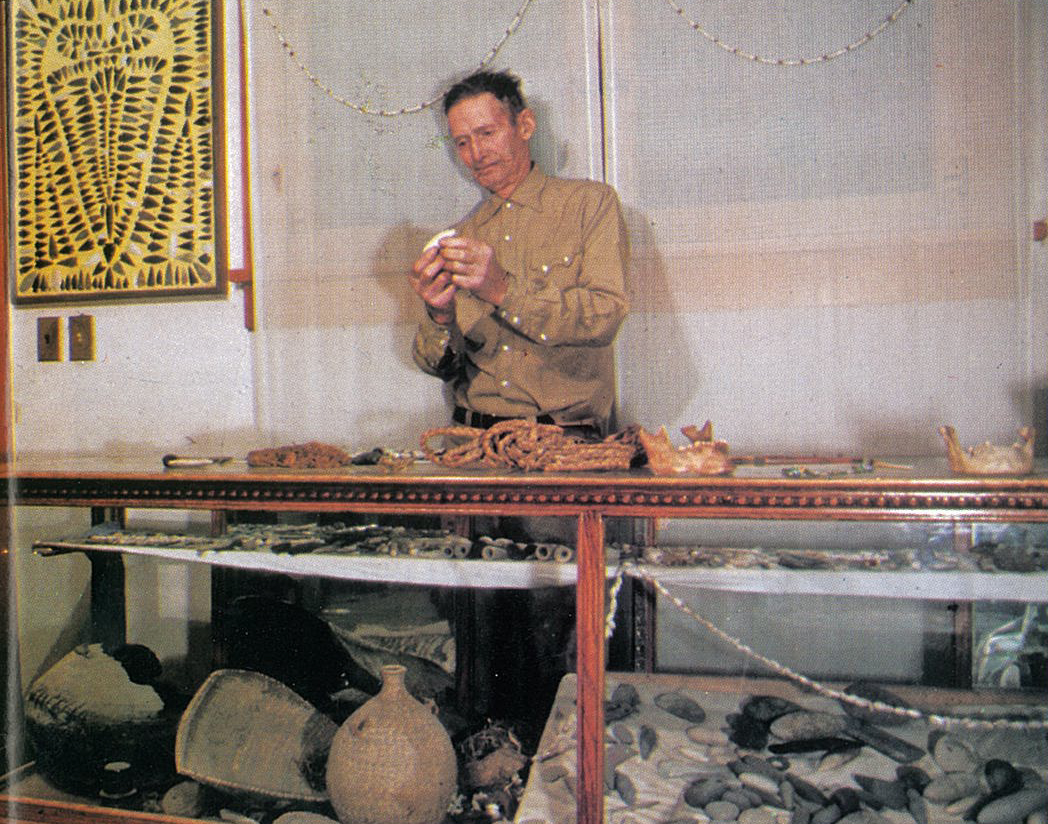

That means Luke has been on the trail of arrowheads – and other Indian artifacts – for 65 years. Today he has what is probably the largest private collection in Nevada. His arrowheads alone number about 40,000, although he’s never really kept count. About 7,500 of his favorite “points” are attractively mounted in cases that line the walls of his home in Fallon in the heart of land that was once Paiute Country.

“I didn’t know I was getting into one of the best arrowhead hunting areas of Nevada,” Luke says, recalling his move to Fallon from Reno in 1913. But he hasn’t confined his hunting to Churchill County. He has traced ancient Indian trails all over the state, picking up thousands of arrowheads and a fascinating assortment of other artifacts – some of them Indian, others dating back thousands of years before the Indian cultures arose. While his collection focuses on Paiute items, it also includes many Shoshone and Washo artifacts.

With a twinkle in his eye, Luke delights in asking visitors if they can guess the purpose of some of his ancient artifacts. He holds up a tangle of string, for example, with tiny animal teeth attached – it turns out to be an ancient fishing line. A tiny six-inch bow was once the plaything of a hunter-to-be; what looks like a granite “top” for spinning is instead a crude drill. The purpose of other items remains a mystery to Luke. “Arkologists,” as he calls them, offer various, often conflicting explanations. Luke, on the other hand, is quite content to live with question marks, admiring the items for their workmanship and primitive beauty.

Luke can spin off a story about each one of his artifacts. He has plenty of anecdotes about his younger days, when he and friends went on informal artifact hunting expeditions. But his favorite stories deal with history, such as the fierce battle between Major William Ormsby’s troops and the Paiute Indians at Pyramid Lake in May 1860.

If his eyes light up while telling it – and they do – it is because Luke sees the battle so clearly in his mind. He knows the terrain of the battle site like the back of his hand, and he’s stood at the spot where Major Ormsby was killed. He can. reconstruct almost every event of that infamous day, as well as other battles in which the Indians fought to retain their ancient lands. Luke hasn’t picked up all those arrowheads without picking up a lot of history too.

The huge oak display cabinet in Luke’s den shows the variety of his collection. In the cabinet are Stone Age pendants, tiny animal carvings and talismanic effigies, bone pipes, abalone shell jewelry and ornaments, sleek bone tools, two ancient human jawbones, incredibly fine woven Indian baskets, heshe necklaces, a Paiute sandal woven from rush (Juncus), and an arrow shaft.

But arrowheads are by far the most numerous items in the collection. Their history, though shrouded in obscurity, tells one of the most important chapters in Nevada’s past.

The game which early hunters brought to camp sustained Nevada’s early natives for more than 12,000 years – more than 100 times the number of years the white man has been in the state. Long before the Paiute and other Indian cultures developed, Nevada was populated by primitive but ingenious Stone Age peoples who hunted wooly mammoths, giant sloths, ancient species of bison, camels, horses, and other now-extinct beasts. These early natives developed the grooved stone “Clovis” spear points – an advance so important it has been termed the “atomic bomb of their time.”

The “Desert Archaic Culture” (about 10,000 to 2,000 B.C.) was followed by the Pueblo-Anasazi Culture and . the Lovelock Culture, the latter named after Lovelock Cave, formed by the waves of the huge, ancient Lake Lahontan. “We used to chase mustangs out there,” says Luke, who visited the cave after scientists had excavated it, unearthing some of the most significant archaeological finds in Nevada. Scientific investigation began in 1912 – but not until miners had hauled off 250 tons of bat guano for fertilizer, destroying countless artifacts in the process.

In the 500 years before the coming of the white man, Nevada was occupied largely by native bands of Paiutes, Shoshone and Washo Indians. Most of Luke’s arrowpoints and artifacts date from this period.

The points range from “bird points” less than an inch long to a huge volcanic glass point that measures close to seven inches. Pre-Indian hunters used these larger points on spears, or atl-atls, to kill large game. Smaller points were all the Paiutes, Washo and Shoshones required to take more common game such as deer, antelope, and ducks. The Fallon area was once less arid than it is now, and its many lakes supported plenty of wildlife and, in turn, Indian life.

Most of the. points that line Luke’s walls are made from agate, jasper or obsidian, with a few of slate. He points with special pride to a magnificent, crystal clear arrowpoint chipped from a piece of clear quartz. Another favorite is made from black and red Wainwright obsidian. Its shape is unusually complicated, with delicate projections at the base and a point which is still as sharp as a needle.

While most of the arrowpoints have -projections at the base, used for binding them to the arrow shaft, some lack any projection at all. “We call them fishtail points,” says Luke, although they actually resemble fish without tails. Luke has been told that these were “poison points” used in warfare. Since the sleek, simple point was detachable, it could be retrieved. “They had no ears on ’em to hang them up,” Luke explains, “so they could be pulled out.”

Luke has one arrowhead which the Indian user never retrieved. He found it embedded in the ribcage of one of the many human skeletons he has encountered in the desert. Holding that point, knowing that in some ancient day it killed a man, one begins to understand the paradox of the arrowhead, which could take human life as well as sustain it.

Except for the two ancient jawbones on his curio cabinet, Luke has left undisturbed the skeletons he has found. His reverence for Indian burial sites is reflected in a story he hesitates to tell to strangers. It concerns the body of a young squaw he found years ago buried behind a boulder in a cave near Pyramid Lake. Luke speculates that she must have been an important member of her clan, for her body was carefully mummified by wrapping it in buckskin. She was buried with her prized possessions – baskets, jewelry, shell trinkets – none of which he disturbed. “I already had so many Indian artifacts,” he says, “that I asked myself ‘What could I possibly want with more?’ So I left her as she was.” Luke often wonders whether that squaw still lies undisturbed in the darkness of the cave.

Luke has only one arrow shaft with point attached. The Paiutes made their arrows of greasewood and cane; time has turned most of them to dust. The few arrows that survive were either preserved in buckskin wrappings or protected from the elements in caves. The lashings are still intact on this rare arrow – demonstrating the purpose of those “ears” at the base of the arrowhead. Sinew or cord was wound around them and then tied firmly to the arrow. Luke has replaced the missing feathers at the opposite end to make a complete arrow.

“An old timer, now dead about 20 years, told me he never picked up an arrow that had been shot and lost,” says Luke. But that old timer – who often hunted for points with Luke – did find a six-foot bow wrapped in buckskin. That’s far larger than the average Paiute bow, which measured about three and a half feet or less.

Although not a scholar with regard to his Indian items, Luke is a master of the art of finding arrowheads. He began learning as a boy when he lived in Reno. “Me ‘n friends would go along the river and up on Peavine Mountain,” he recalls. The points were plentiful if one knew how to spot them. He also recalls the days when “Us kids used to follow the river down to Pat McCarran’s ranch 15 miles below Reno. We’d hunt all the way.” That was about a 30 mile round trip.

Best sites for “finds,” Luke says, are around springs. “Where there’s a spring, you’ll usually find a campsite.” The presence of chipped rocks, heavy metates or mortars, also indicate ancient camp locations. Metates, the oval stones on which Indians ground seeds and grain, were too heavy to lug around, so they’re a sure sign of Indian settlement. Many of the arrowheads found at such sites are poorly-shaped discards.

Many Indian campsites were located along shorelines of lakes which have since disappeared (distribution of river water in Nevada has changed remarkably since the white man settled there; huge lakes have disappeared and irrigation has brought life to thousands of acres of once arid desert land).

Luke has many tricks for spotting arrowheads, but mostly he relies on his keen eye. One method: “When the sun is ‘one or two feet’ off the horizon, they get a ‘different flicker’ to them and you can spot ’em easier.”

The arrowhead hunting in Nevada isn’t as good today as it used to be. Throngs of arrowhead collectors have come to Nevada from throughout the U.S., and Luke wonders if they’ve left any stone unturned. “People have come from California and from every direction,” he says. “Now, the Hondas and four-wheel-drive stuff, they’re tearing up the landscape, making it even harder to find points, especially in good condition.”

Yet, says Luke, “there’s more stuff covered up than we’ll ever turn up.” Hopefully, future finds by trained scientists will tell us more of Nevada’s Indian heritage. Today Paiutes come from a nearby reservation to see Luke’s collection. Most of them are young Indians, Luke says, and they have a keen interest in the artifacts of their ancestors.

Other visitors react differently, however. Luke shakes his head. “You know,” he says, “some people just stand there and all they can say is ‘How much you got ’em insured for?’ or ‘What’re they worth?’ ” Luke places no dollar value on his arrowheads and other artifacts ‘– to him these things are priceless.

To make sure they are preserved in that spirit, he has already given some of his best artifacts to the Churchill County Museum. Eventually, it will house the rest of Luke’s collection, giving Fallon one of the finest Indian museums in the state.

And all those Indian items will have found a fitting resting place, right in the heart of Paiute country. They’ll always be part of The Luke Collection, a gift from a man who always walked with a keen eye for yet another find, so that the past would not be lost to the present … or to the future.

Editor’s Note, 1976: Since 1959, Nevada laws have required that persons investigating, exploring or excavati11g historic or prehistoric sites have a valid and current permit issued through the Nevada State Museum. Failure to have such a permit is a misdemeanor. Details may be learned by consulting the Nevada Revised Statutes, Chapter 381.

Editor’s Note, 2020: George Luke died Sept. 26, 1986. After his passing, his collection was returned to his wife, and is no longer available for view. The Churchil County Museum in Fallon does have an impressive collection of points and artifacts worthy of a visit.