Nevada Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

May – June 2014

Combat, prohibition, and the emergence of Las Vegas shape the next era in Nevada’s history.

BY RON SOODALTER

With the twentieth century came developments in travel, communication, and international commerce that had shrunk the globe, involving virtually every nation in one another’s affairs—and the United States was no exception. World War I began in 1914, and within two years, America would abandon its earlier isolationist policy, and commit first money and munitions, and then troops, to the conflict.

With the twentieth century came developments in travel, communication, and international commerce that had shrunk the globe, involving virtually every nation in one another’s affairs—and the United States was no exception. World War I began in 1914, and within two years, America would abandon its earlier isolationist policy, and commit first money and munitions, and then troops, to the conflict.

In 1916, the federal government put out the call to the National Guard troops of a number of western states, for the purpose of patrolling the Mexican border—a wise precaution in light of future developments. In January of the following year, a coded telegram was sent from Germany to Mexico, proposing a military alliance between the two countries in the event that the United States entered the war. It promised not only to compensate Mexico financially, but also to “reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.” It also revealed Germany’s intention of commencing “unrestricted submarine warfare.” The telegram was intercepted and decoded by the British, and shared with the Americans. Suddenly, with the prospect of armed conflict only a border away, the European war had become much more immediate.

NEVADA AND THE GREAT WAR

Most states responded to Wilson’s call for National Guard troops with enthusiasm. Nevada, however, was so sparsely settled that it had never felt the need for a National Guard unit. The state had formed a militia during the Spanish-American War, but it ultimately served no viable purpose, and was disbanded in 1906. Unable to respond to the federal summons, a sheepish Governor Emmet Boyle wrote to the secretary of war proposing to gather several hundred volunteers, but the secretary rejected the offer.

In June 1916, Congress passed the National Defense Act, federalizing the National Guard, and mandating each participating state to raise a National Guard unit of 600 men within a year’s time. Governor Boyle—to his further embarrassment— was unable to raise the requisite number of volunteers, and at the very moment the United States was preparing to enter World War I, Nevada could respond with only nine government-sponsored civilian rifle clubs and an ROTC unit from the state university.

However, in 1917, the state legislature voted an appropriation of $25,000, to meet any “military demands, which may be made upon the State of Nevada by the President or the Government of the United States.” A new Nevada State Council of Defense served as liaison between the federal government and the people of the state, conveying news of war-related projects, as well as formal requests and orders. Aiding in its efforts was a number of regional councils. When the Selective Service Act was passed by Congress that same year, mandating that all males between the ages of 21 and 31 register at their local draft boards on June 5, Governor Boyle declared that day a state holiday, prompting a spate of patriotic demonstrations across Nevada. Approximately 31,000 Nevadans registered.

In total, nearly 4,000 Nevada inductees and some 1,500 volunteers entered military service. Nevada contributed as many men to the war, proportionate to its overall population, as any state in the Union. As members of the Ninety-First—or, Wild West Division—the newly minted troops were shipped to France in July 1918, and from there to the front, where they participated in the Battle of St. Mihiel, the Meuse-Argonne offensive, and the Ypres-Lys offensives. The Division, which was comprised of men from several western states, suffered nearly 6,000 casualties in less than two months.

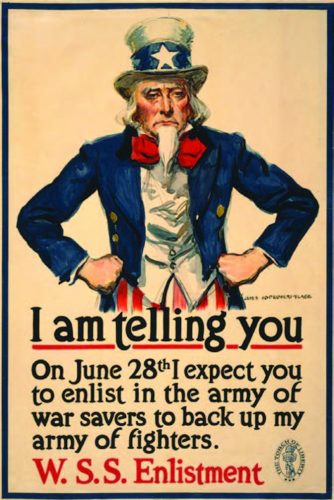

Initially, many Americans questioned the nation’s involvement in a largely European struggle. Rather than attempt to explain the complexities that brought the world—and the United States—into armed conflict, the Wilson Administration disseminated its own brand of jingoism to the American public. This was largely accomplished through the newly formed propaganda machine known as the Creel Committee on Public Information. Helmed by muckraking journalist George Creel, the Committee opted for a simplistic approach to patriotism, idealism, and love of freedom. The Huns, the moral argument went, were intent upon destroying the free nations of the world, and it was America’s responsibility to make the world safe for democracy. The choice was simple: Support the fight for freedom, or side with the Central Powers. The Committee sent out speakers, films, and printed material, and contributed incendiary text and cartoons to the nation’s newspapers, listing the outrages committed by the Germans and their allies— much of which was pure invention. Whole communities attended rallies, and joined in on rousing choruses of “Mademoiselle from Armentieres,” “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” and “Pack up your Troubles in your Old Kit-Bag.”

The propaganda campaign had the desired effect. The resultant war hysteria— a flood of what one chronicler called “narrow nationalism”—allowed little room for reason or tolerance, and the fallout was felt throughout Nevada, as well as in other states where German and Austrian populations were found.

According to the 1910 state census, Germans in Nevada numbered around 2,000, forming the state’s second-largest group of immigrants, followed by some 1,000 Austrians. Although the population was far from huge, and despite the fact that many had long since sunk their roots in the state, native Nevadans tended to view them with suspicion that occasionally developed into outright animosity. Those German families isolated on farms and in small towns received the brunt of the abuse. But even in areas where the German population was strong and well established, such as Douglas County, citizens acted overtly to suppress their German neighbors. In Minden, for example, the teaching of German in school was halted, and conducting Lutheran church services in German, disallowed. In other cities and towns, members of Nevada’s German and Austrian communities were socially ostracized, and singled out for abuse.

According to the 1910 state census, Germans in Nevada numbered around 2,000, forming the state’s second-largest group of immigrants, followed by some 1,000 Austrians. Although the population was far from huge, and despite the fact that many had long since sunk their roots in the state, native Nevadans tended to view them with suspicion that occasionally developed into outright animosity. Those German families isolated on farms and in small towns received the brunt of the abuse. But even in areas where the German population was strong and well established, such as Douglas County, citizens acted overtly to suppress their German neighbors. In Minden, for example, the teaching of German in school was halted, and conducting Lutheran church services in German, disallowed. In other cities and towns, members of Nevada’s German and Austrian communities were socially ostracized, and singled out for abuse.

Other ethnic minorities and immigrant groups, such as Greeks and Serbs—whom many native Nevadans tended to confuse with Germans—went out of their way to distance themselves from what the newspapers were broadly (and inaccurately) referring to as “Austro-Hungarians.” They staged their own rallies, where they spoke loudly in favor of the war effort, and in communities such as McGill, Ruth and Ely, organized and marched in what came to be called loyalty parades.

Meanwhile, statewide support for the war effort grew exponentially, as mothers proudly sent their sons off to fight for global democracy, amidst the wild approbation of their neighbors. In Ely, the day before the town’s 65 newly inducted young soldiers were to take the train to Camp Lewis, Washington, for training, the local citizenry treated them to a movie, a dance, rousing speeches, and at dawn the next morning, a full marching band that led their way to the station. Scenes such as this, along with flag-planting ceremonies, fund drives, and inspirational addresses by volunteer and government speakers, were played and replayed across Nevada until the signing of the Armistice in November, 1918.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF BOOM

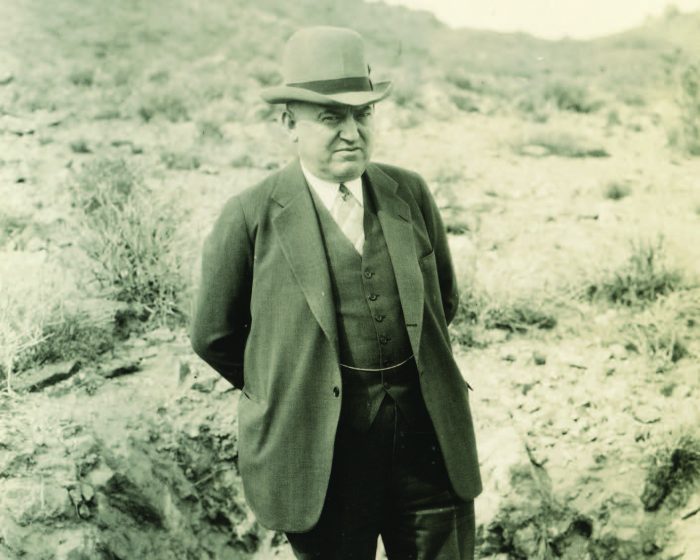

Nevada’s various commercial enterprises were given a significant boost by the war. As early as 1914—more than two years before America entered the conflict—no less a figure than George Wingfield, mining magnate and one of the state’s richest and most powerful men, predicted that all aspects of Nevada’s businesses stood to benefit from it. The Nevada State Journal published an August 7 interview with Wingfield, in which he referred to the European war as a “gilt-edged market for all [Nevada’s] products….”

He predicted a “big demand for mutton and beef,” as well as a “strong market for horses, which will give us a chance to work off our less desirable stock into the war for restocking with a better quality of animals.” As time would prove, Wingfield’s optimism was well founded. Increasing demands saw farmers irrigating more and more land, while ranchers expanded their herds of cattle, horses, and sheep. The increasing demand—coupled with the elevated price of food—brought fiscal well being to Nevada’s farmers and stockmen.

In addition to foretelling a surge in agriculture, Wingfield also prophesied a boom in the state’s mining industry. His predictions were, if anything, understated. The rapidly growing demand for copper saw production more than triple in the two years following 1914, reaching $25 million in 1916. New mines were opened up, adding to the existing centers of copper extraction and processing. The global war effort also called for silver and lead, and the heretofore-failing camps of Eureka and Pioche saw new life, while Goldfield and Tonopah—both of which had begun to fray around the edges—produced again at levels that kept them viable throughout the war. By 1918, Nevada’s mineral industries had reached a production high of nearly $49 million. At its peak, the Comstock had never attained such a level.

BANNING THE BOOZE

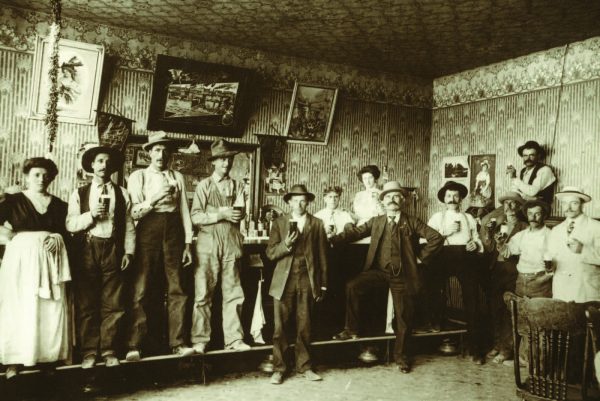

At the same time Nevada’s industries were striving to meet America’s demands, a nationwide moral crusade was underway that sought to ban the manufacture and sale of alcohol. The campaign, which had been gathering steam for nearly a century, sought to eradicate a commodity that had long been an integral part of American life.

Liquor was woven into the fabric of America from its earliest days. Before the Pilgrims sailed for the New World, they loaded the hold of the Mayflower with kegs of beer. In 1792, at the same time he was raising a 13,000-man militia to put down the so-called Whiskey Rebellion, President George Washington was run- ning his own private distillery at Mount Vernon. There was no occasion—from baptisms to weddings and funerals, from elections to barn raisings and public executions—in which alcohol did not play at least a supporting role.

Intoxicating liquor was, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, “used by everybody, repudiated by nobody.” On land and at sea, soldiers, sailors, and workingmen of all types were given a fixed daily allotment of rum or whiskey. Americans drank as a matter of course, at all hours of the day, from early morning (John Adams consumed a large glass of hard cider every day on waking) till late at night. Doctors throughout the nation prescribed various types of distilled alcohol to their patients as a preferred alternative to the consumption of impure water. To coin a phrase, liquor was as American as applejack.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Americans—mostly men—were drinking vast amounts of hard liquor, considerably more than is consumed today. Alcoholism was commonplace, and a growing portion of the population felt that something should be done. As far back as the found- ing of the American Temperance Society in 1826, followed in 1840 by the ironically named Washingtonian Society, sobriety- minded Americans had been attempting to slow or halt the consumption of liquor. Increasingly, alcohol was blamed for all that was wrong with America, as a growing number of temperance unions convinced more and more people to take the pledge.

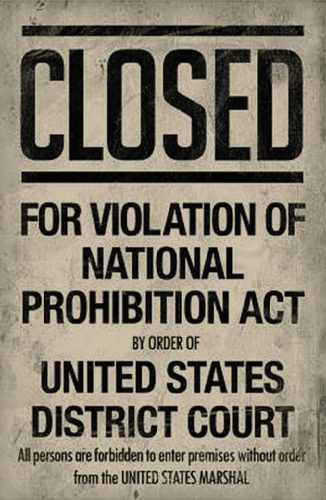

Not surprisingly, with millions of troops off fighting, reformers used the war as an opportunity to promote the movement. In 1917, a rider was attached to the Food and Fuel Control—or, Lever—Act, outlawing the production of alcohol from grain. President Wilson used this law, which went into effect in October 1918, to justify shutting down the nation’s breweries. By the time the armistice was signed ending World War I, there was a strong enough temperance groundswell to push the 18th Amendment through Congress. Effective January 16, 1920, the amendment, and its subsequent enabling law, the Volstead Act, officially banned the nationwide manufacture, sale, and transportation of liquor, finally making America dry. Herbert Hoover called the new law “the great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far-reaching in purpose”—and it would soon prove an abysmal failure.

Over a year earlier, in a well-intentioned but ill-conceived attempt to lower the crime rate, improve the general health, and raise the morals of its citizens, the Nevada legislature passed its own temperance initiative, decreeing a statewide prohibition of intoxicating beverages.

Although the measure passed by a nearly 4,200-vote margin, there were still thousands in the state who refused to give up drinking. At first, this determination expressed itself with the state’s population—which numbered around 90,000— receiving some 10,000 prescriptions for “medicinal alcohol.” Although numerous doctors and pharmacists discovered a windfall in the prescribing and issuing of medicinal booze, this stopgap measure could not accommodate the clamoring market of Nevada’s miners, cowboys, businessmen, laborers, congressmen—and, for the first time, women—demanding their libations. Consequently, a thriving moonshining and bootlegging industry was born. The resultant systematic bribery of jurists and law enforcement officers introduced a heretofore-unknown widespread corruption that swept the state.

Suddenly, speakeasies sprang up in several Nevada cities and towns, their owners relying on the corruptibility of lawmen for their survival. Officers on all levels accept- ed bribes to look the other way, or to warn the bootleggers and “speaks” of pending raids. In 1924, Nevada’s federal prohibition chief was convicted of misconduct in office. He was forced to pay a $500 fine, and to leave office. This is not to say that there were not officers who strove to enforce the law. In Tonopah, in one week alone, agents made 31 arrests. More often than not, however, those honest prosecutors who actually attempted to cadge a guilty verdict frequently found that jurors—a growing number of whom opposed prohibition—were unwilling to vote for conviction. Unable to obtain convictions for liquor violations, the forces of law in McGill tried—unsuccessfully—to force the bootleggers to leave town or face vagrancy charges. United States District Attorney William Woodburn, addressing the Reno Lions’ Club in January 1920, bemoaned the fact that, before prohibition, Reno had some 50 saloons, whereas now, it boasted at least 75 bootlegging establishments.

One of Nevada’s more lyrically inclined imbibers wrote a poem that appeared in Godwin’s Weekly, lamenting the outlawing of liquor. It begins:

I remember, I remember, The State where I was born,

That used to be so wringing wet, And is now so forlorn.

From Pioche to Winnemucca, It was heaven – Just to think That it now is really arid

And a man can’t get a drink.

There was a mystique frequently associated with the moonshiner, both in Nevada and elsewhere. He was seen to be addressing a common need, and was generally looked upon at worst as a harmless outlaw, and at best as a folk hero. As one chronicler of the period observed, “He is a sort of illegal pet, carefully protected from extermination by both the law and society, but hunted with just enough diligence to make him constantly aware that he is a criminal.”

Nonetheless, although the distiller of home brew might have been looked upon as a quaint example of local color, often his product was anything but harmless. The manufacture of illicit alcohol gave rise to its own set of serious, and sometimes deadly, issues. Without official oversight in the manufacture of liquor, the quality of the whiskey often dropped radically. While some moonshiners paid close attention to their process, turning out a decent whiskey, many callous opportunists—see- ing the potential for fast and easy prof- its—jumped into the distilling business.

Their carelessly made moonshine often contained lead. Distillers would deliberately add creosote for color, and embalming fluid for “kick.” These men cut corners and turned out a product—often referred to as “Jackass Brandy,” or “Jake” —that was not only substandard but also dangerous, in some cases resulting in blindness, paralysis, and death. As one popular blues ballad of the period bemoaned,

I can’t eat, I can’t talk,

Been drinkin’ mean Jake, Lord, Now I can’t walk…

District Attorney Woodburn complained, “In no place in the state except Reno and possibly Tonopah is there any good liquor left. In every other place jack- ass brandy, which is nothing but poison, is being distributed.” In the seven years following the passage of the Prohibition Act, there were reportedly 50,000 deaths nationwide, resulting from the consumption of bad whiskey. Although there does not appear to have been a study documenting the number of such deaths in Nevada, it can be assumed that enough Jake was being cooked and consumed to account for at least a few premature exits.

Another offshoot of the illicit alcohol trade in the state was violence. Illegal syndicates sprang up to establish and maintain control of the liquor business, and with the advent of organized crime, shootouts were inevitable—and there were a number of them. On one occasion, on a bone-chilling day in mid-December, 1922, two prohibition agents attempted to arrest a pair of moonshiners on a ranch outside of Palisade. The suspects shot one of them, a young officer named Atha “Nick” Carter, and ran off, leaving him bleeding in the snow. The agents’ driver had panicked at the first fire and sped away, stranding the two officers. Carter’s partner trudged 14 miles for help, but by the time it arrived, Carter had succumbed to a combination of blood loss and exposure.

Not all the mayhem was on the side of the bootleggers. After an unarmed bootlegger was shot and killed by a prohibition agent near Pyramid Lake, a Nevada editor opined, “[I]n this great country of ours, human life is held mighty cheap.”

According to Phillip Earl, former curator of history for the Nevada Historical Society, various folktales sprang up around the manufacture of illicit alcohol—and since Nevada was an agrarian state, a number of these stories related to the livestock. Tonopah had more than its share of illegal stills, tucked snugly along its back streets. As one story goes, when the moonshiners finished with the mash—the fermentable mixture of grain and water used in the making of whiskey—they would simply throw it in the gutters, or into the alleys. Roving burros would ferret out and consume the mash, with the result that Tonopah was inundated with a population of drunken burros, stumbling down the street and running into cars.

One tale features a number of Nevada farmers, who bootlegged on the side, drying their mash once its function in the distilling process had been fulfilled, and feeding it to their chickens. The result was a yard full of inebriated foul. Yet another story tells of three federal prohibition agents who were out hunting moonshiners in the Battle Mountain area. They stopped at a café for lunch, and noticed three or four pigs walking erratically outside, and occasionally falling over. On a hunch, the agents followed the pigs home, and arrested their owner in the process of making whiskey.

Ultimately, the prohibition law hit Ne- vada in the purse. It had the unanticipated effect of denying the state much-needed tax revenues that had previously been generated from the now-defunct legal liquor business. In the end, despite the legislature’s best intentions, Nevada’s pioneer prohibition law had the opposite results its framers and supporters had intended. Crime had risen dramatically, general health had declined, the state was losing significant tax dollars, and it could safely be argued that the morals of its citizens had not improved in the slightest. Eventually, most Nevadans—even those who had harbored the best intentions for a dry state—came to see the prohibition laws on both the state and national levels for the abject failures they were, and came out in favor of repeal. One group of protesters went so far as to form an organization that called itself “The Order of Camels”—quite probably in deference to that animal’s prodigious drinking capacity.

Many public officials across the state simply chose to ignore the law. Reno Mayor Edwin E. Roberts, for instance, officially ordered the members of the city police force not to make any arrests whatsoever for violations of the Volstead Act, thereby leaving only the federal prohibition officers to chase down the city’s bootleggers and arrest the violators.

In 1923, the state lawmakers repealed the Nevada prohibition law, but could do nothing about the federal statute. Three years later, Nevada’s citizens voted overwhelmingly to petition Congress to call a constitutional convention for the specific purpose of repealing the 18th Amendment. Unfortunately, they would have to wait for a legal drink until December 1933, when the 21st amendment would finally end prohibition.

WHAT HAPPENS IN VEGAS

In the early days of prohibition, the town that would one day become one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world was showing every sign of becoming Nevada’s “sin city.” Just a few years earlier, Las Vegas was, in the words of historian Phillip Earl, “nothing but rattlesnakes, scorpions, and a narrow road to Los Angeles.”

In the early days of prohibition, the town that would one day become one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world was showing every sign of becoming Nevada’s “sin city.” Just a few years earlier, Las Vegas was, in the words of historian Phillip Earl, “nothing but rattlesnakes, scorpions, and a narrow road to Los Angeles.”

Established in 1905 as a watering stop along the Union Pacific’s Los Angeles-to-Salt Lake City route, Las Vegas was built as a railroad town, with everything radiating out from the tracks. Because it had to service the trains, crews and passengers on a round-the-clock basis, Las Vegas was what was known as a 24-hour town. Almost from the beginning, it offered liquor and gambling—and in short order, prostitution—in such casinos as the Gem and the more upscale Arizona Club. The railroad stipulated that the saloons and casinos must be restricted to two city blocks, that began at the corner of Fremont and First streets, continuing past Ogden to Stewart streets, and were known simply as blocks 15 and 16.

When Nevada banned gambling in 1909, the Las Vegas houses paid no attention. Despite the introduction of prohibition, blocks 15 and 16 continued to offer liquor, gambling, and women to both the train crews and the passengers. There was nothing glamorous about it; services were of the rough-and-ready variety. One observer recalled, “Climactically and socially the atmosphere was repellent. It was a man’s town.” In 1921, Las Vegas took two hits that all but turned it into a ghost town. First, the Railroad Labor Board voted to cut hourly wages, and a union of some million and a half railroad workers went on a nationwide strike. When the strike was finally resolved, the railroad decided to relocate its repair shops from Las Vegas to Caliente, further up the line. Although people still traveled to blocks 15 and 16 for their illicit booze and entertainment, the steady business from passengers and crews dried up, and stayed dry until the end of the decade.

In late December 1928, just before the nation plummeted into a crippling depression, the tough little town’s luck began to change for the better. President Coolidge signed into law the Boulder Canyon Project Act, approving the largest civil engineering project in the nation’s history: the building of a dam that would harness the power of the Colorado River. Although the site was shifted to Black Canyon, and the resulting structure would later be officially christened Hoover Dam, it would always be known as Boulder Dam.

Within months, thousands of workers began to pour into the area. Although nearby Las Vegas had campaigned to become the official headquarters for the dam project, the Bureau of Reclamation, along with a conglomerate of construction companies, built Boulder City—a neatly laid out ready-made community for the workers. Along with the model city came a stringent set of rules: no gambling, no women, and especially, no drinking.

Therefore, the 5,000 residents of Las Vegas could not have been happier when the construction of a rail line was begun, to run the 20 miles from the project site to their little Gomorrah of the desert. What the laborers were denied in camp would be made available to them on a full-time basis in Las Vegas. By the time the first load of concrete was poured in Black Canyon in 1931, Las Vegas was enjoying the illicit bounties of prosperity. Wrote historian John M. Beville, “The earlier population of mule skinners, freighters, section hands, miners, ranchers and ‘rails,’ yielded…to Boulder Dam construction workers: high scalers, rig operators, engineers, and foremen.”

COASTING THROUGH THE 1920s

When the war ended, so too did the high level of productivity it had brought to Nevada. Within a year or so, mineral production had declined to less than half what it had been in 1918. And as the call for farm and ranch products lessened, so too did the prices. The state’s population—never numerous to begin with—fell off by the thousands, to just above 77,000 in 1920.

Despite a less-than-promising beginning to the 1920s, however, things soon picked up, presaging a healthy economy for Nevada throughout the decade. There developed a growing industrial demand for the state’s minerals, especially copper. And sheep and cattle ranchers enjoyed continued stability, and expanded their operations to meet a growing demand for their products. For Nevada, as well as for the country at large, the decade of the 1920s was one of prosperity and security.

Further benefitting the people of Nevada, both the state and federal legislatures voted significant funding for the building of roads and highways. In fact, Nevada’s largest single expenditure following the war was its multimillion-dollar contribution to the state highway system. The automobile had quickly become America’s primary mode of travel, and roads were a growing necessity. In addition to providing statewide employment, Nevada’s road-building projects benefited the state in a number of other ways. The roads—especially the transcontinental Lincoln and Victory highways—opened the state to tourism, and encouraged the rise of businesses and communities along the way. Further enhancing the state’s revenues were the increased gasoline and license taxes.

In 1925, to celebrate the modernization of Nevada’s system of roads, the state legislature voted the appropriation of sufficient funds for a Nevada Transcontinental Highways Exposition. The event was to be staged in Reno, upon completion of the Lincoln and Victory highways. When the exposition took place two years later, one of its major features was Idlewild Park. Designed by noted San Francisco landscape architect Donald McLaren, the park was built along the Truckee River just west of downtown Reno. It still remains a popular tourist attraction today. As the website describes it, the park “features mature trees, large expanses of grass, two rentable picnic shelters, playgrounds, ball fields, a municipal pool, skate park, walk- ing and biking paths, a train ride, Reno’s Municipal Rose Garden, and small lakes for fishing and feeding waterfowl. Idlewild Park is the site of Reno’s annual Earth Day Celebration.” The only original structure still standing from the time of the exposition is the mission revival-style California Building, a gift from the state of California, and built to honor “the memory of those who gave the last full measure of devotion to this nation.”

Besides overseeing the construction of 1,000 miles of Nevada roads, Democratic Governor James G. Scrugham, who had been elected in 1922, introduced a number of other progressive advances. He established Elko airport as the terminus for the first scheduled airmail run in America, and set aside specific areas within Ne- vada’s forest reserves for game refuges, public parks, and recreation grounds. The 15 recreation areas he created were placed under the aegis of the State Game and Fish Commission, and served as the forerunners of the Nevada State Park system.

Scrugham was also responsible for the preservation of such valuable archeological sites as Lost City and Lovelock Cave. A maturing Nevada was looking to its past, as well as its future. Throughout the 1920s, Nevada’s economy fared well, and as the decade neared its end, prospects for continued prosperity seemed bright. All the signs were positive. By 1928, mineral production had made a significant recovery from its post-war decline. To repay Nevada for the moneys it had lent the Union during the Civil War, Congress designated southwestern Nevada for the building of a $3.5 million munitions storage depot and a power dam was approved at a cost of around $125 million.

Then came word of the stock market crash. It began on October 25, 1929, and culminated four days later, on what has come to be called “Black Tuesday.” With the wipeout of the value of a full 40 percent of common stock, it triggered the Great Depression. Over the next few years, the national economy tumbled. Stock prices continued to fall, and as they dropped beyond the point of recovery, investors found it impossible to sell their shares and retrieve their money. And when the banks began to lose their investments as well, depositors panicked, and rushed to withdraw their savings, driving the banks further into ruin. Financial institutions around the country closed their doors, causing yet another panic as many millions of Americans lost their life savings. Spending was cut back, first for luxury items, then for the necessities, with the result that businesses radically reduced both staffing and production. Countless businesses and industries eventually went bankrupt. Within months of the crash, mining in Nevada fell off by nearly 50 percent.

But in 1929, the worst of the Great Depression was still in the future. To Nevadans, word of the crash seemed at first a disturbing, but remote, piece of news. After all, Nevada was as far removed from the machinations of Wall Street as it was possible for a state to be—or so it seemed. Nevada’s Republican Governor Fred Balzar, in his 1931 Condition of the State message to the Nevada State Legislature, blithely predicted, “[T]he existing Nation-wide condition of financial stress is but lightly felt within our own borders, when comparisons are made with conditions prevailing in other States, and this is partly due to our solid financial standing and partly due to the large Federal expenditures which have heretofore been made within the State, or those authorized to be made.”

He was being overly optimistic. The Depression would inevitably challenge Nevada in many ways, as it would every state in the Union, as well as the nations of the world. But it was a challenge Nevadans would rise to meet – in both conventional and unorthodox ways.

Read the Entire 8-Part Series

Part I: The Unknown Territory

Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

Part III: Twain, Trains, & The Pony Express

Part IV: Into the New Century

Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

Part VI: Gambling, Gold and Government Projects

Part VII: To War and Beyond

Part VIII: Looking Forward, Looking Back