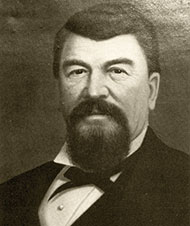

Yesterday: Reno’s First Robber Baron

May – June 2018

Founding father Myron Lake was a man of vision and avarice, whose toll bridge had Reno citizens both coming and going. Some said he had created a town in order to bleed it.

BY GUY LOUIS ROCHA

His death was not so deeply deplored by the community at large as it should have been,” wrote Allen C. Bragg, editor of the “Reno Evening Gazette” and a rare friend of Myron Charles Lake. The founder of Reno had made many enemies while he lived. As far as most people who knew him were concerned, his passing in 1884 went unmourned.

It wasn’t that Lake lacked wealth, fame, and prominence in his community. Through his early toll bridge and hostelry on the Truckee, he had guided commercial traffic between the northern Sierra and the Comstock. Later he enticed the Central Pacific to establish a station at his humble but busy crossing, and Reno was born.

He had been a shrewd man, with force and vision, and he did many things for Reno. His instincts, however, were not those of public service for which founding fathers are so well known. His actions frequently hurt and angered citizens of the town he established, and they eventually turned against him. Some said that Lake had created a town in order to bleed it.

The passage of time has obscured much of what we know about Lake. His controversial business practices, a lengthy and much-publicized divorce, and even the date when Lake’s Crossing was established in the Truckee Meadows have been forgotten, overlooked, or inaccurately represented.

Let’s set the record straight on Myron Lake.

The date of Lake’s arrival on the Truckee has been disputed and misrepresented for many years. The year, in fact, was 1861, as attested by, an advertisement Lake ran in the “Territorial Enterprise” announcing his purchase of Fuller’s Crossing. But there is much more to the Lake story than just the question of when he came to the Truckee Meadows.

Lake clearly demonstrated his business acumen when he acquired Fuller’s Crossing and then obtained a toll road franchise from the Nevada Territorial Legislature in 1862. With the franchise, the wily entrepreneur acquired a monopoly on the use of the Sierra Valley Road (now Virginia Street) and its valuable Comstock traffic for the next 10 years.

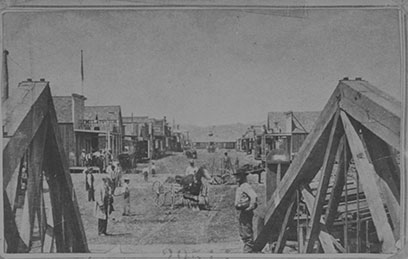

In the late 1860s, the building of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad, which would cross the Truckee Meadows, aroused the best and the worst interests of the man destined to become Reno’s founder. While the Central Pacific Railroad’s track crew hastily advanced toward Lake’s Crossing in early 1868, Myron Lake was negotiating with company officials for a townsite on his property. The railroad interests found themselves considering an offer they could not refuse. Lake got his town, named after Civil War General Jesse L. Reno, and the Central Pacific received a right-of-way across Lake’s property and, according to editor Bragg, every alternate block in the new town-site.

“When the railroad reached Reno,” Bragg wrote, “it stopped nearly all the traffic that had been crossing the mountains via Donner Lake, and the vast number of teams engaged in hauling freight were immediately transferred to the road between Reno, Virginia City, Carson City, Empire and points further south, and Mr. Lake began making money hand over fist.”

Lake charged what must have been considered an exorbitant toll, $1 for each horse-drawn vehicle, and other fees for larger wagon teams, horseriders, pedestrians, and domestic animals. His account books, Bragg tells us, showed toll bridge receipts totaling as much as $2,500 per day. A check of Lake’s records shows his average daily take to be about $250 to $300-at a time when the Comstock’s miners were among the highest paid in the world in their profession at $4 a day. In all, Lake was earning more than $100,000 a year.

Besides his lucrative toll road franchise, Lake had other ways to fill his growing coffers. In 1869, he built a new and larger hotel at a cost of $23,000 after a fire destroyed Fuller’s original structure. The following year he constructed a brick kiln to meet the demand for building materials in Reno. Both businesses received a brisk and profitable trade.

In 1871 Lake established the South Addition directly across the Truckee River from Reno. Clever as always, Lake offered the Washoe County Commissioners a parcel of land in his new addition as a site for a proposed courthouse. The Nevada Legislature had recently moved the county seat from Washoe City to Reno, and Lake recognized that the courthouse would make a nice centerpiece to the South Addition. More importantly, this avaricious businessman surely knew that the townspeople of Reno would have to cross his bridge to transact their official business at the county courthouse. Despite some loud and lengthy protests from Reno citizens, Lake got his courthouse.

From the community’s inception, popular sentiment in Reno called for the purchase of Lake’s toll bridge. Lake, for obvious reasons, would not hear of it. Their purchase efforts blocked, Renoites circulated a petition demanding a toll reduction in 1869. Lake vehemently protested action, arguing that “he and his bridge were both here before Reno was town.” His protests resulted in a six-month delay of the petition’s consideration. Finally, in June 1869, the commissioners passed a general 25-cent rate reduction. Lake seemed to take the action stride, but many of Reno’s citizens were satisfied only temporarily.

In 1870, there was some talk of Washoe County building a “free bridge” to span the Truckee River below Lake’s. Nothing came of it. The following year criticism of Lake’s toll bridge monopoly escalated, especially after the county commissioners approved the location of the new courthouse across the river from Reno. At the same time, irate businessmen cut delivery service to the growing population on the south side of the river because their clerks had to pay each time they crossed Lake’s bridge. Area residents, whether they lived on the north or south side of the Truckee, found that Lake had them both coming and going.

Events came to a head on the bridge question during 1872 and early 1873. A sign of things to come occurred when Lake lost a legal battle in the Nevada Supreme Court over the construction of the Virginia & Truckee Railroad bridge. Lake had noticed that hundreds of people were using the newly-built bridge just east of his crossing to avoid the toll. Claiming that the structure had been built within a one mile limit of his operation, Lake retaliated by running a fence across the railroad bridge. Reno’s “first citizen” was compelled to back down as neither the V & T interests, nor the courts, sympathized with his argument or actions.

The Washoe County Commission also challenged Lake’s stranglehold on the area’s main commercial artery. The toll road south from Lake’s bridge, today’s South Virginia Street, was declared a public thoroughfare. Shortly thereafter the commissioners, acting upon a grand jury report critical of county toll road operators, ordered Lake to repair his toll road from the Truckee River north to the California border. When the commissiners threatened to void Lake’s franchise for not paying the required percentage of his toll profits to the county, the threats came to naught.

Finally on Jan. 6, 1873, Washoe County , Commissioners refused to grant Myron Lake an extension and declared the bridge and toll road a public highway.

But Lake was not about to give up a good thing that easily. Openly defying the commissioners, he locked the bridge’s gate, and, according to Allen Bragg, “stood on the bridge with a sixshooter and still demanded his toll from everyone who crossed.” Only those people who paid the toll could pass. Moreover, Lake refused to make good his deed for the courthouse land and the $1,500 he had promised the community toward the construction of the building.

A battle royal pitting Lake against Washoe County officials soon raged on the banks of the Truckee. Following a heated dispute with a teamster who refused to pay the toll, the sheriff arrested Lake for obstructing a public thoroughfare. Reno Justice of the Peace James J. Poor fined Lake $20 and ordered the intransigent toll keeper to leave the bridge gate unlocked.

Although Lake won his appeal in the district court and was found not guilty of obstructing a public highway, he discovered, much to his dismay, that he had won the battle of the bridge but not the war.

The county commissioners also were ready to fight the “bridge war” in court. The board ordered the district attorney, William M. Broadman, to take action against Lake to determine if he had the right to continue collecting tolls. While few Renoites openly sympathized with Lake’s plight, a small but vocal number of citizens expressed their disapproval over the costs of a lengthy court fight. On the other hand, the letter from “Old Brick” in a local paper expressed the community’s general sentiments: “Prove to the old Shylock if he did trap us on the courthouse, he can’t on the toll road and bridge. Shave him as he shaves everybody. If that’s his style give him the full benefit of it.”

And so it came to pass. The Nevada Supreme Court finally upheld the district court ruling in favor of the state in May 1873, and the justices declared that Lake’s bridge would henceforth be “free.”

An armistice between the two warring parties came that September. Lake, facing the prospect of another court battle over his guarantees of land and money for the courthouse, presented the county with the promised $1,500 and the deed.

Nonetheless, controversy continued to plague Myron Lake. In late 1879, his wife Jane filed a divorce suit in Washoe County District Court, and Reno’s founding father found himself charged with extreme mental and physical cruelty.

Jane had married Myron Lake on September 9, 1864, in Lassen County, California. Fifteen years later, she alleged that her husband beat her and threatened her life on a number of occasions. Moreover, Lake had accused his wife in vile language “of being unchaste and unfaithful to him.” The final abuse which led to the divorce action occurred on Oct. 15, 1879. According to the divorce record, Lake told his wife “to leave his house and family, that he wanted to be rid of her, that she could go to hell, that if she would go where he would never see her again he would give her $10,000.”

The highly publicized divorce case lasted three years. In 1882, the Nevada Supreme Court, upholding the district court’s ruling, decided in Jane Lake’s favor. While Myron Lake was able to retain his extensive holdings in the Truckee Meadows and elsewhere, Jane received custody of Myron Charles Jr., $200-a-month alimony, and court costs. One year later, Myron remarried.

Myron Lake died in Reno on June 20, 1884, at the age of 56, a wealthy and prominent man. But even the grim reaper couldn’t keep him out of court. Jane Lake immediately contested her former spouse’s will and the court action dragged on for many months. In the end, Jane and her heirs got the last measure of revenge when the court validated an earlier will that favored her interests. Lake’s troubles had followed him to the grave.

When we recall the West’s early pioneers, like Lake and others, we tend to romanticize. The men and women who traversed the Great American Desert, crossed the Isthmus, or rounded the Horn to seek their fortune represented the complete spectrum of society, from the best to the worst. If these people had something in common, it was the fact that they were more adventurous than their Eastern counterpart and were willing to gamble, sometimes with their lives, on the chance of bettering their circumstance. Above all, they were mortal-not saints-and subject to all the virtues and vices inherent in the human condition. Myron Charles Lake is a case in point.

Whether he is called the father of Reno or Washoe’s first robber baron, this Nevada pioneer has left us a rich and controversial legacy.