Nevada’s Outlaws

May – June 2019

Part 2: More tales of the dastardly desperados that roamed the Silver State.

BY RON SOODALTER

As described in part one of Nevada’s Outlaws—published in the July/August 2017 issue—Nevada was every bit as wild as such legendary Western Gomorrahs as Deadwood, Tombstone, and Dodge City. The lure of gold and silver and the prospect of easy pickings drew lawbreakers like flies—miscreants as deadly and desperate as the Daltons, the Youngers, or the James Brothers.

Although the wild times extended well into the twentieth century (the last stage robbery occurred in 1916), the most active period for Nevada’s bad men—and women—was in the 1850-1870s, when the search for precious metals was at its height, and those who sought to benefit from the labor of others were at their busiest. It was also a time in which local citizens, in the absence of a recognized force of law, formed vigilance committees and dispensed justice with a strong rope and a short drop. And in those rare instances when the vigilantes got it wrong, an after-the-fact apology counted for little.

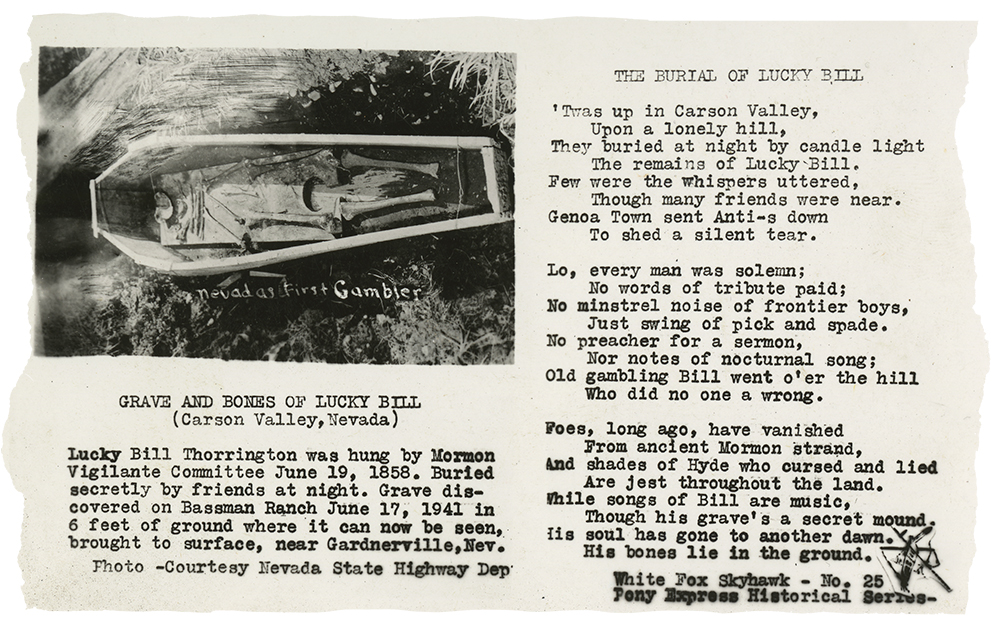

AN UNLUCKY DAY FOR LUCKY BILL

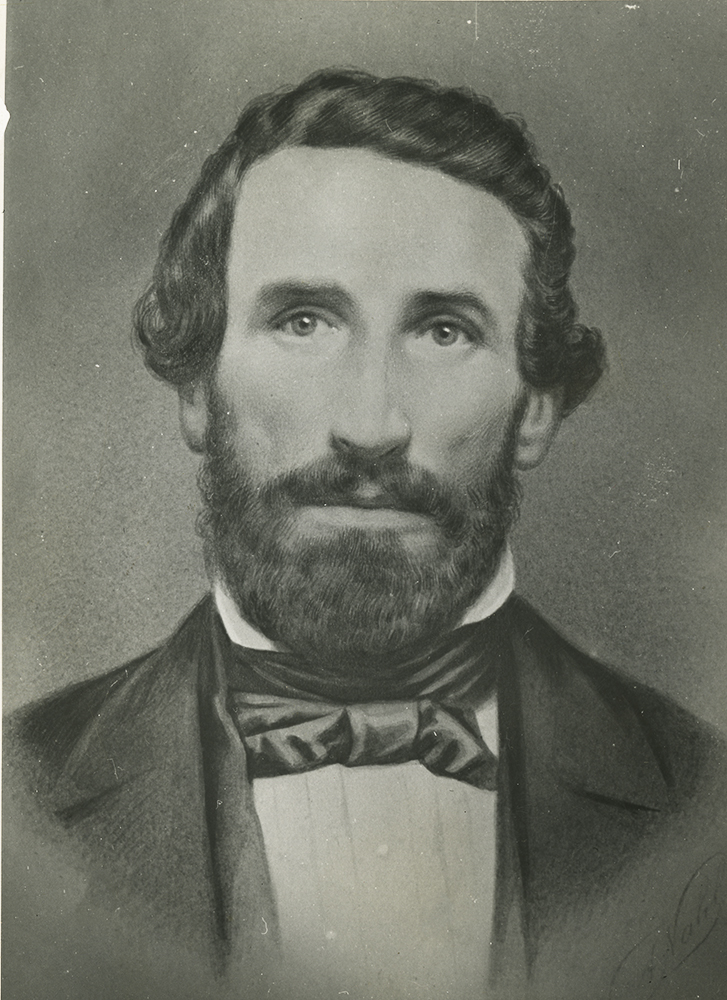

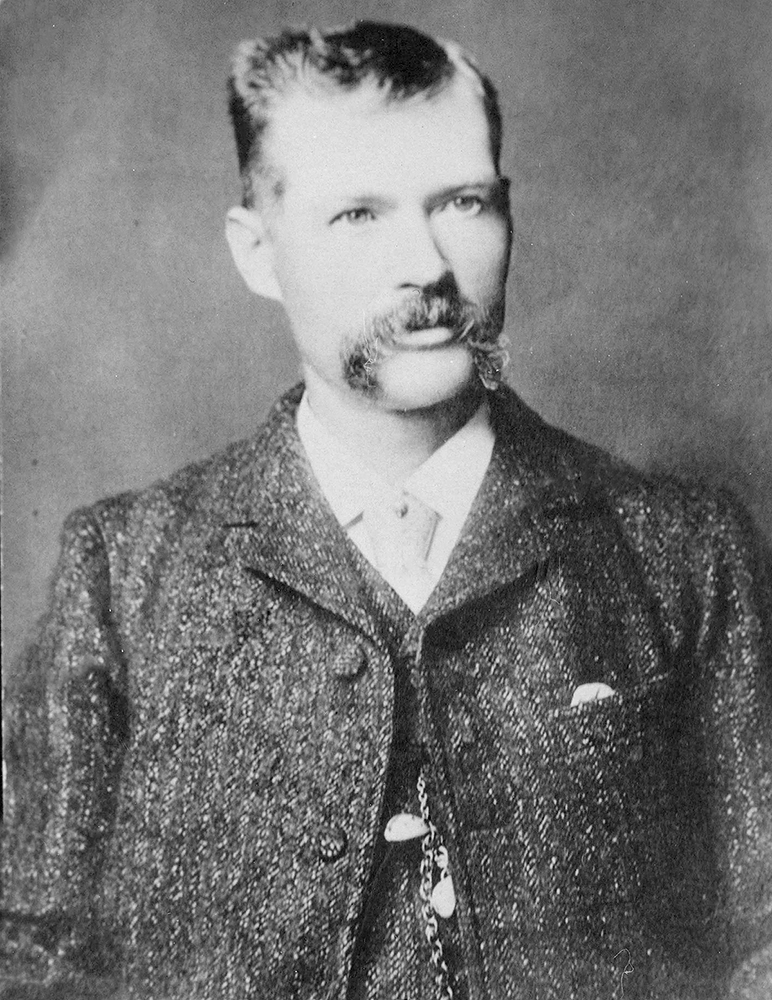

Such, apparently, was the case with William “Lucky Bill” Thorington. A handsome, charming six-footer in his mid-40s, Thorington first appeared in Genoa in 1853, and immediately set himself up in business. He bought a mill, operated a hotel, and opened a toll road and trading post for westering emigrants. But it was as a skilled professional gambler that he made his reputation. Although he seemed always to win (hence the sobriquet “Lucky Bill”), he was apparently well-liked. As one chronicler stated, “Lucky Bill could make a man count it a distinction to lose his shirt at a single turn of the card.”

Thorington was blessed with a young son and beautiful wife, and life was good. By all reports, he was a caring and generous member of the community. As a local later recalled, “[A] better neighbor never lived near any man, or a better friend to the weary traveler.”

Unfortunately, Carson Valley had become a refuge for bad men, and Thorington was less than discerning about the company he kept, or the friends he made. This applied to women as well. Around 1856, he impregnated a woman named Martha Lamb, and moved her onto his ranch. Among the fiercely anti-Mormon members of the community, this gave rise to the idea that he was a polygamous member of the Latter-Day Saints, and according to some, this was the underlying reason he was hanged.

Around that time, William Ormsby came to Genoa. A trader by profession, he was by all accounts also vain, ambitious, opinionated, and excitable. Ormsby assumed the running of the community, including the newly-formed vigilance committee, which Thorington and others vehemently opposed. He and Lucky Bill soon became bitter enemies.

In December 1857, a man named William C. Edwards murdered the leading citizen of Merced County, and escaped to Genoa. As one historian states, “Edwards sought out a man who had a reputation for helping all who asked, Lucky Bill Thorington.” He told Thorington that he had acted in self-defense, and asked him to hide his money while he looked up old friends. A gullible Thorington complied.

Shortly thereafter, Edwards and his cronies murdered a cattleman and stole his herd. He returned to Thorington’s door, again swearing his innocence, and seeking help in escaping. The vigilantes soon captured Edwards, and arrested Lucky Bill and several others. Edwards soon confessed, and Ormsby immediately helped organize a “trial” for Lucky Bill. Reviewing the transcript, a later chronicler wrote, “Not a thing appears there implicating Lucky Bill in anything except the attempt to secure the murderer’s escape. Edwards swore positively that he had assured Lucky Bill that he was innocent.”

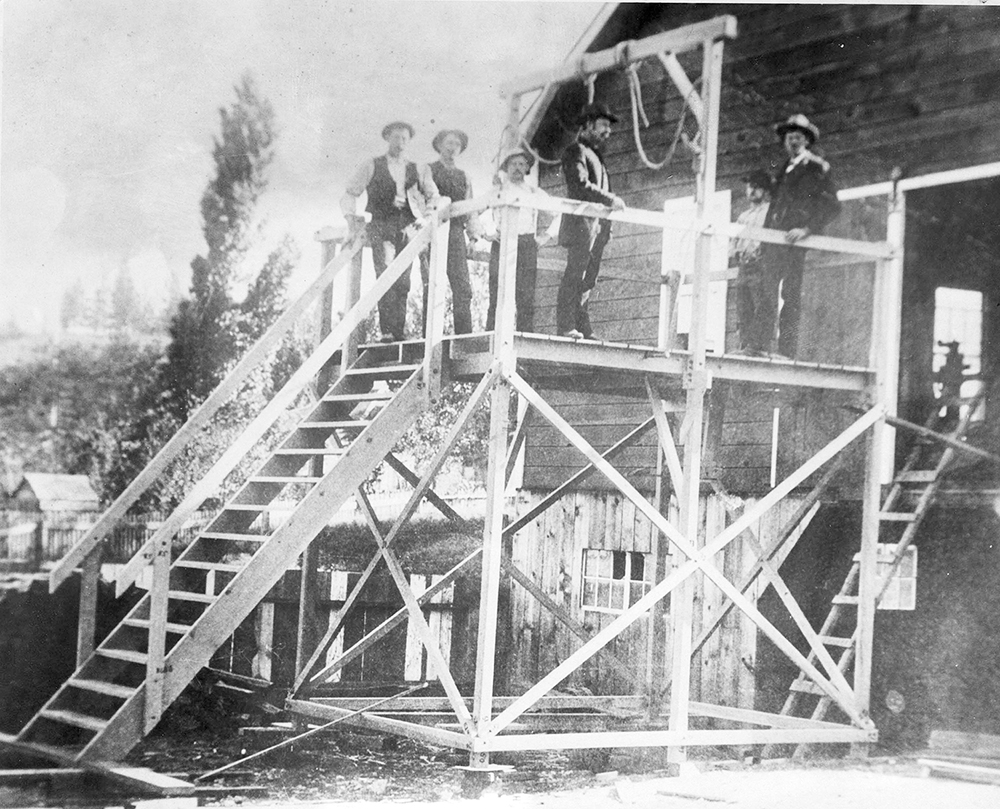

Nonetheless, the verdict was a foregone conclusion. Even as the trial was taking place, vigilantes were constructing a gallows within earshot. The gambler died with dignity and courage, shouting, “I ain’t never lived a hog, and I ain’t gonna die like one, screamin’ about bein’ butchered!” A noose encircled his neck, and after singing “The Last Rose of Summer,” he leapt to his death. Somewhere, someone owes “Lucky Bill” Thorington an apology.

THE MAN NOBODY LIKED

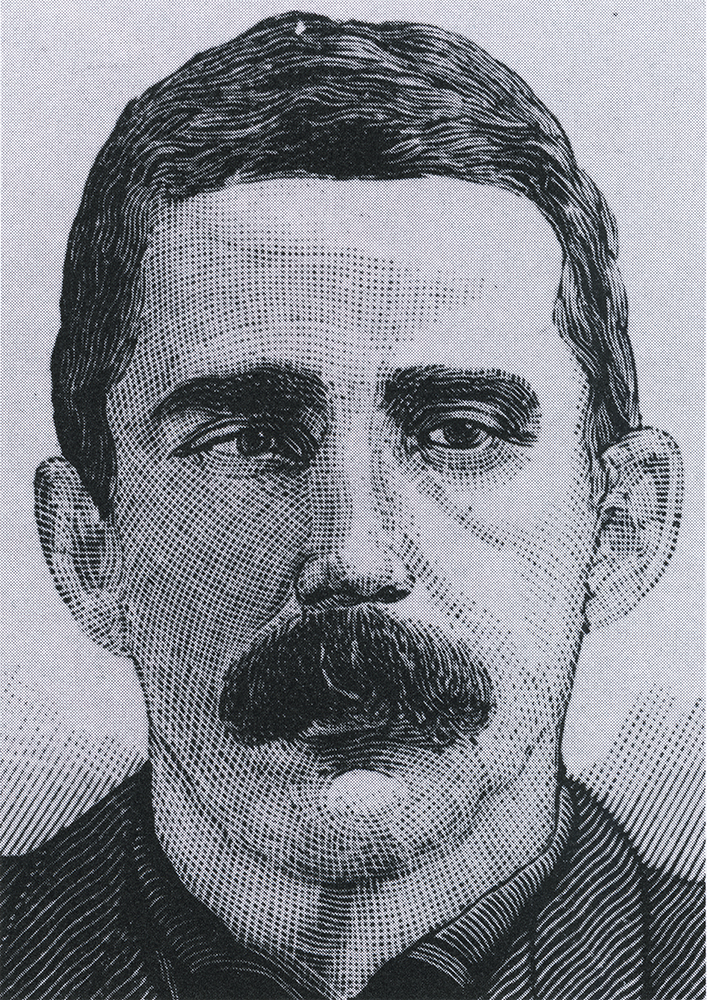

Unlike Lucky Bill, there were few if any who would speak for the moral character of Morgan Courtney. According to a contemporary article in the “Reese River Reveille,” “Courtney was one of the most desperate and bloodthirsty characters that ever disgraced a mining town….” Given the roster of desperados who populated Nevada’s boom towns, that speaks volumes.

Courtney, whose birth name was Richard (or John) Moriarty, was a remorseless killer. In 1868, after a brief altercation in a Virginia City saloon he shot a bartender in the back, killing him. Changing his name to Morgan Courtney, the miscreant “went on the dodge,” appearing two years later in Pioche, a wide-open mining town that would host some 40 killings between 1870 and 1875. Courtney and Pioche were well-matched.

The young thug immediately hired his gun out to a rich mining concern to drive claim jumpers away. He gathered a gang of like-minded hooligans, and charged the band of intruders, killing one and putting the others to flight.

Shortly thereafter, Courtney became involved in a verbal altercation with a local named John Sullivan in a saloon. Unaware of the adage about not bringing a knife to a gunfight, Sullivan pulled his knife on Courtney while swearing at him, whereupon Courtney shot him dead—at a distance of 30 feet. Courtney was tried for murder, but in that time and place, cursing a man by impugning his mother was grounds for homicide, and he was acquitted.

After a forced visit to Virginia City where he was tried and acquitted of killing the bartender, Courtney returned to Pioche, where he started keeping company with a volatile young prostitute. Customers aside, she was also showering her affections on a local named James McKinney, a whiskey and laudanum addict whom the local newspaper described as “a low order of man” who was “never known to do a day’s work.”

After a forced visit to Virginia City where he was tried and acquitted of killing the bartender, Courtney returned to Pioche, where he started keeping company with a volatile young prostitute. Customers aside, she was also showering her affections on a local named James McKinney, a whiskey and laudanum addict whom the local newspaper described as “a low order of man” who was “never known to do a day’s work.”

Addressing him with the same ill-chosen epithet that Sullivan had spewed at him, Courtney ordered McKinney out of town. Instead, McKinney opted to surprise Courtney, shooting him five times in the back. Not surprisingly, Courtney succumbed. Tried for murder, McKinney was acquitted, for the very reason the jury had freed Courtney: You simply didn’t call a man a son-of-a-b*!ch and expect to survive it.

The local newspaper expressed little grief over Courtney’s demise, describing him in words that would eventually appear on his grave marker: “feared by some, detested by others, and respected by few….”

BIG LIZZIE AND LITTLE JO

Elizabeth and Josiah Potts were an odd-looking couple. Elizabeth was a very large woman, married to a man half her size. Neither was a seasoned outlaw, but together, they authored one of the most shocking and convoluted murders in Nevada history.

The Pottses were born in England, where they wed prior to immigrating to Wisconsin. Josiah, a machinist with the Central Pacific, moved his family as the railroad ordained, first to Utah, and then to Carlin.

A brief separation resulted in Elizabeth traveling solo to Sacramento, where she met and bigamously wed an unsuspecting carpenter named Miles Faucett. Shortly thereafter, she returned to Josiah, and Miles—who had told friends Elizabeth owed him money—followed her, taking up residence in the Potts home until he purchased a nearby ranch.

On the night of Jan. 1, 1888, Faucett visited the Pottses, ostensibly to get Elizabeth to pay him his money. He was never seen alive again. His ranch house was found to have been ransacked, and everything of value taken. The Pottses soon moved to Rock Springs, Wyoming, after renting their house to a family named Brewer and telling neighbors that Faucett had been called away on business.

The following January, George Brewer discovered various partially burned and dismembered sections of Miles Faucett buried in the basement. Local lore insists that Faucett’s ghost directed the Brewers to his resting place. The Pottses were extradited to stand trial, and subsequently convicted and sentenced to hang. “The mind naturally recoils with horror,” the judge stated in passing sentence, “at the thought that anyone can become so lost to the common instincts of humanity.”

Elizabeth attempted suicide by slashing her wrists, but she was revived. In Elko on June 20, 1890, loudly proclaiming their innocence, the couple died on a double gallows, before an audience of 52 lawmen and journalists. Owing to her prodigious size—she had gained even more weight in her cell—Elizabeth was nearly decapitated by the drop, whereas skinny Josiah expired of strangulation. Elizabeth Potts became the only woman in Nevada history to be executed.

BREAKOUT

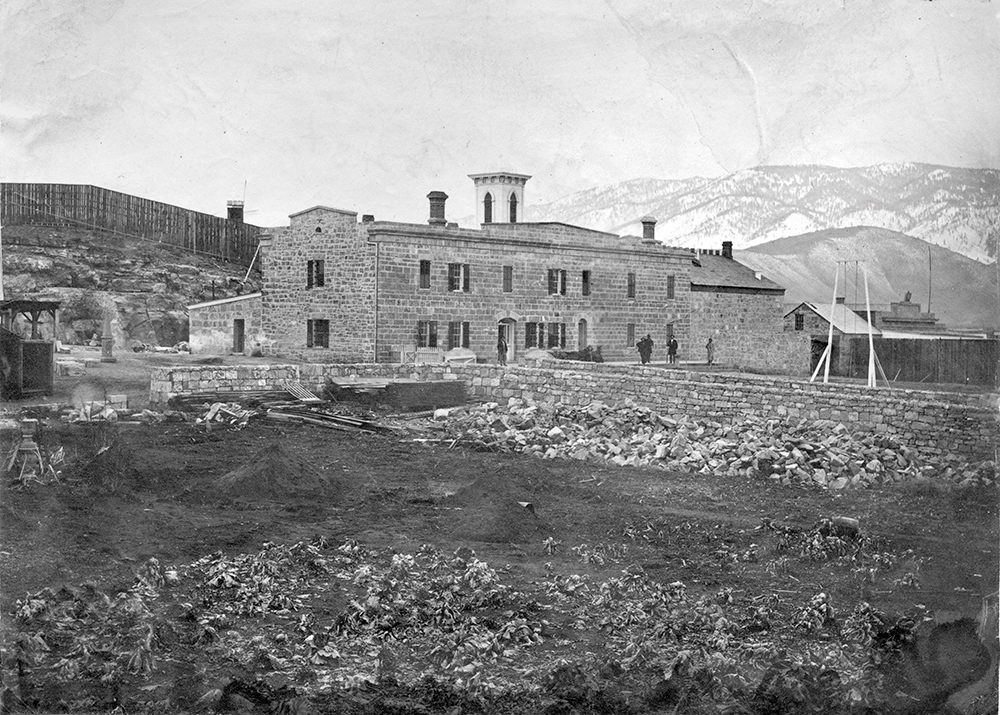

Western penitentiaries were, by design, extremely unpleasant, and some were virtually escape-proof. Such was not the case with Carson City’s Nevada State Prison. On a frigid Sept.17, 1871, 29 inmates staged the largest breakout in the nation’s history.

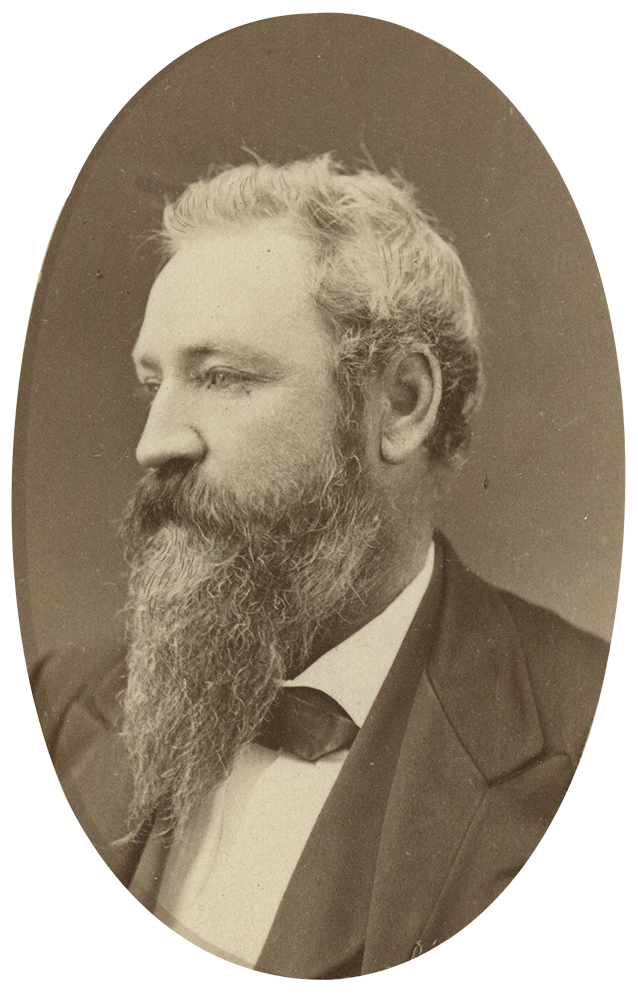

It was a Sunday, and most of the guards were off duty. As evening fell, the prisoners, using handmade weapons, overpowered a guard and climbed through a hole in the ceiling. Following the crawl space to the ceiling over the warden’s quarters, they smashed through, surprising the warden’s wife, daughter, and mother-in-law at dinner. Warden Frank Denver, who was also the state’s lieutenant governor, rushed into the room, pistol in hand. Inmates beat him to the ground and shot him in the stomach with his own pistol.

Seizing Denver’s keys, the escapees opened the armory doors and stole several rifles, pistols, and shotguns, as well as thousands of rounds of ammunition. A gun battle ensued between the now-heavily armed inmates and the few remaining guards. The guards took the worst of it; three were wounded, and the local hotel owner, who had run to their aid, was shot dead. One inmate suffered a superficial arm wound.

The escapees scattered in all directions. One was captured days later while basking in a hot springs, reportedly claiming all he’d wanted was a hot bath; but the remaining 28 continued to elude pursuers, much to the embarrassment of local law enforcement. Crossing into California, five of the inmates seized a horse belonging to a teenager, senselessly killing the boy. Some histories insist that the youth was riding for the Pony Express, but that institution had ceased operations a decade before. An aroused Mono County posse immediately took up the chase, overtaking the five escapees near what has come to be called Convict Lake. In the ensuing firefight, two posse men were killed.

However, a newly formed posse captured three of the five inmates. As they were conveying their prisoners to jail, the posse was stopped by a band of vigilantes, who summarily hanged two of them. For some reason, they voted not to kill the third.

Ultimately, only 18 or 19 of the 29 escapees were recaptured. Warden Denver recovered from his wound, but not from the scandal surrounding the escape. When Governor L.R. “Old Bullhorns” Bradley ordered him to surrender his position to a new appointee, Denver refused. The governor then sent 60 soldiers and a small field piece to convince him, and Denver turned the prison over to his successor without further resistance.

LOOKING BACK

Nevada has certainly had its share of bad apples. But through the influence of movies and television, and as far back as the “penny dreadfuls” of the late 1800s, there has blossomed an aura of romance surrounding the Old West’s felons. In fact, the only thing that separates them from the gangsters of the 1930s or the organized crime figures of today is the passage of time. If Morgan Courtney had owned an automatic weapon, he would have used it gleefully. The real early-day heroes were not the ones who sought riches with a pistol, or who killed without remorse, but those who dug in, and scratched a living from unforgiving ground, or labored daily to turn a profit. They were the ones who paved the road to today’s Nevada.