Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 9

May – June 2019

Chapter 2, Part 9: The Lovelock Lion

BY ERIC CACHINERO

Just around suppertime on July 11, 1912, housewives prepared meals, miners clocked in and out, and children played in the streets of the northwest Nevada mining camp of Mazuma. The town rested at the mouth of Seven Troughs Canyon, just below the mining camp of the same name, and on that day, everything seemed normal in this little slab of sagebrush, save for an unusually colossal gathering of somber thunderclouds that hovered just up the canyon.

Then, amid thunderous roars and cloudburst, a biblical tsunami rained down upon the canyon as if Heaven’s bathtub had swiftly cracked in two.

The Seven Troughs Cyanide Plant was the first building to be hit by the 10-foot wall of water that maniacally assaulted the canyon like a liquid freight train. To make matter worse, after the flash flood reduced the plant to splinters, it was now carrying dozens of gallons of deadly cyanide, though that fact made no difference for the unsuspecting residents down the canyon in Mazuma.

A heroic attempt was made to warn the Mazumans of the approaching wave. Seven Troughs Coalition Mining Company Engineer Ed Kalenbauch watched the deadly deluge safely from his office on a hill. After seeing the flood and where it was headed, he phoned an operator in the nearby town of Vernon, who quickly phoned a hotel owner in Mazuma. Though the two were connected, electrical interruptions caused by the weather allowed only one word through before the transmission was lost: “water.”

By that time, it was too late. The flood annihilated Mazuma and in one fell swoop, claimed eight lives—nearly a tenth of the town’s population. A child’s body was found nearly 5 miles away.

WONDEROUS

The lives lost on that fateful day were not in vain. Lessons were learned and future warnings heeded. It’s unfortunately ironic that here in the driest state in the U.S., water can often have dangerous, even deadly consequences. Flash floods are something to be wary of.

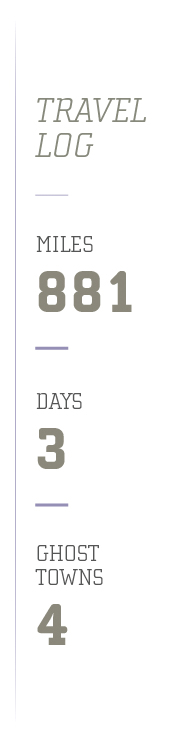

Managing Editor Megg Mueller and I are reminded of this as we set out on our third ghost town trip of the year, careening into the northwestern Nevada desert amid a “chance of scattered rainstorms,” which it turns out, on this day, means it’s pretty much raining as hard as possible only in the directions we want to go. Black clouds line the peaks in the distance as we turn north on Dixie Valley Road toward another handful of historic Nevada mining camps. It’s not long before we pull off the main road en route to Nevada’s most wonderous ghost town: Wonder.

Rich quartz veins were discovered in a dry wash in May 1906, attracting the attention of around 100 zealous prospectors, giving rise to the town of Wonder. By August, the “Wonder Mining News” newspaper was in circulation—as was a rival newspaper—and boasted that the town of Wonder had no mosquitos. Not long after that, a post office was constructed and the town’s drug stores, saloons, cafes, and hotels were built so quickly it was as if they simply grew from the desert dirt. The Nevada Wonder Mining Co. kept the lights on via the reciprocal relationship between its physical ore and the paper ore of East Coast capitalists for nearly 11 years, before the mines ran dry and Wonder became wearisome.

Due to its massive size during its heyday, I’m initially surprised at how little is left of Wonder, before later learning that most of the town was packed up and moved to other mining camps. Concrete mill foundations and a collection of metallic trash mark the site, as does an old outhouse that appropriately reads, “Wonder, Nevada Pop. 0.” We poke around for a bit before heading north into the wet and wild Dixie Valley.

GHOST VALLEY

Though much of Dixie Valley is open to the public, the area is owned by the Naval Air Station Fallon and is used as an electronic warfare range. Skeletons of homes and ranches line much of the valley, as does a host of functional and nonfunctional military equipment. This coupled with the bleak skies, worsening muddy road conditions, and general remoteness of the valley give the drive a truly ghostly feel, but is lightened a bit by the incredibly vibrant rocks in the surrounding hills. After suffering a series of brief map malfunctions (me getting lost), we find the road we need and set off toward the foreign lands of Bolivia.

Bolivia, Nevada was formed in the 1870s as miners from nearby Unionville branched out. Nickle and cobalt were discovered in Bolivia in the 1880s, and brought rise to a leaching plant (failed), and a furnace (exploded). Nothing too spectacular ever came from the town, and it faded out around 1907.

There are wild alpacas in the country of Bolivia. It absolutely wouldn’t surprise me to see one here as we ascend the canyon. Muddy roads and extreme terrain set us searching for the ghost town on foot. The jagged orange cliffs don’t resemble any place I’ve ever seen in Nevada, and I think that this must be what Bolivia the country looks like. The search is made more difficult by the creek rushing down the middle of the road (at times, the road and the creek are indiscernible). We may as well be playing hopscotch with the amount of times we jump back and forth across the creek and are able to just barely make it without falling in. The rain worsens into a downpour just as we eventually come face-to-face with an actual Nevada waterfall about 10-feet tall. We decide that’s a good place to turn around as we hike it back to the car, unsuccessful in exploring Bolivia. I grumble that I’ll be back with my Jeep next time.

More map malfunctions lead us to the north end of the valley, and a sort of interior chaos ensues. “Is that the right road?” “Didn’t we turn back there?” “Are the roads too muddy?” We finally agree on a resounding yes to the last question, and decide it safest to turn around and drive the long way to our destination for the night: Lovelock. We originally had planned to traverse Dixie Valley Road and the connecting roads all the way to Winnemucca, but heed our own advice to be smart about how we travel in the remote backcountry. So, it’s off to Middlegate for a much-needed burger before we start the long haul to Lovelock for the night.

PHANTOM FELINE

It rained all night.

The nighttime downpours fuel unfortunate pessimism. We awake and grab a quick breakfast before getting on the road, leaving ourselves as much time as possible should we become thwarted by rain and muddy roads once again. Luckily the first ghost town of the day—Humboldt City—is located in the Humboldt Range just off Interstate 80. We reach the ghost town with ease.

Humboldt City was formed when silver was discovered in the canyon in 1860. Initial conflicts with American Indians in the area led to stunted growth of the town; however, an 1861 rush brought 200 people and Humboldt City was up and running. On May 2, 1863, the “Humboldt Register” painted Humboldt City as, “A picturesque and beautiful village containing some 200 well-built houses, some of which are handsome edifices, and many beautiful gardens that attest the taste and industry of the inhabitants. A beautiful, crystal stream of water diverted from its natural course runs a little babbling stream through every street.” At one time, plans were made to divert a 61-mile ditch from the Humboldt River to supply the town with water, and there were even serious talks of diverting the entire river, but they never came to fruition. By 1869, the short-lived Humboldt City was no more.

As we approach the ghost town, I remark that I’m surprised we haven’t seen any deer in the canyon as it looks like the perfect place for them. We step out and walk for less than 30 seconds amid the dew-kissed sagebrush before Megg abruptly shouts, “I’ve got an animal!” as something leaps up about 20-yards from her. The scenario is nothing out of the ordinary, and I hear a quick crashing through the tall brush and expect to see the white behind of a mule deer doe bouncing up the adjacent side hill.

That’s what I expect, but it’s not what happens.

We sit relatively silent looking for the deer before I make my usual go-to joke that it must have been a mountain lion. My sentence is interrupted by an unfamiliar guttural growl that slices the morning silence.

“Ggrrraaarrrhh.” “Ggrrrrraaaarrhhh.”

Megg and I stare silently in disbelief. We don’t make a sound for another minute before the short spurts of gravelly feline snarls return, and they’re close. We listen on for a couple more minutes, and the series of growls continues, then disappears completely. The situation we find ourselves in is that the cat ran in the direction of our vehicle, and the ghost town is behind us. We make the decision to move away from the cat, instead of toward it, taking quick refuge in Humboldt City’s structures. After some time snapping photos, we cautiously walk back to our vehicle, and manage to escape unharmed.

I am 100 percent confident that what we experienced is, in fact, a feline growl. I am not 100 percent confident that the growl was that of a mountain lion, and could have been that of a bobcat. The only thing I’m left to do at this point is wonder; however, one more detail stands out. I didn’t get a look at the animal, but Megg saw a flash of its butt, which she describes as “tan.” The thing about bobcat butts is, they have a very noticeable pattern of light and dark spots on them. Mountain lion butts, on the other hand, are undeniably tan.

You decide.

MUCK

The rest of the day is spent wondering out loud the identity of our (luckily) friendly feline, and experiencing the harsh reality that some days just aren’t ideal for backroads ghost towning. We exit I-80 and drive about 8 miles to what we thought would be the ghost town of Tungsten.

Private property.

We turn around and hop back on the highway, driving around 40 miles west into the Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Mud.

The roads are far too sloppy for us to continue, so we turn around and head south around the west side of Rye Patch Reservoir in search of a road that our atlas tells us will take us out into the Seven Troughs Range.

No such road exists.

Feeling a bit discouraged at this point, we head back to Lovelock to gas up before giving it one more shot. We drive the main roads out to the Seven Troughs area, as rainclouds release their contents as randomly as a fireworks display. Mazuma, Seven Troughs, and Farrell are the ghost towns in our cross hairs, though our struggle finally leaves us stopped in the middle of the dirt road, unable to go further.

The type of mud we encounter isn’t the type that’s found in a high-end spa, nor the type that lightly tamps down the dust on a warm spring day. The mud we encounter is a liar and a backstabber. It’s the type of mud that rests just underneath an eighth inch of dry topsoil, waiting till you’ve driven just a bit too far before it reveals itself. This is the mud that acts like a trapdoor spider—once you’re unfortunate enough to drive upon it, it leaps out from hiding and grabs onto all four tires, spinning and swirling you into the roadside ditches and ruts where you encounter an even more paralyzing, binding quicksand mud that may as well just swallow entire vehicles whole.

The type of mud we encounter isn’t the type that’s found in a high-end spa, nor the type that lightly tamps down the dust on a warm spring day. The mud we encounter is a liar and a backstabber. It’s the type of mud that rests just underneath an eighth inch of dry topsoil, waiting till you’ve driven just a bit too far before it reveals itself. This is the mud that acts like a trapdoor spider—once you’re unfortunate enough to drive upon it, it leaps out from hiding and grabs onto all four tires, spinning and swirling you into the roadside ditches and ruts where you encounter an even more paralyzing, binding quicksand mud that may as well just swallow entire vehicles whole.

Given that Nevada Magazine doesn’t own a recovery helicopter, we admit defeat, heading back to Lovelock for the night.

CURSED

It didn’t rain all night.

As I awake, sun peaks through my hotel room window swirling optimism that the roads may have dried out. Enough, at least, that we could take a second crack at finding Mazuma. We head back out and see that in fact, the trapdoor spider has retreated just enough to allow us to pass, and we reach Mazuma.

Mazuma—derived from a Yiddish slang word for money—was founded in 1907. The Mazuma Hills gold mine was a successful operation, attracting a host of businesses, including a two-story bank, three-story hotel, and other mainstays. The town was otherwise flourishing until the catastrophic flood that razed it. After the tragedy ensued, the town mill was reconstructed, though was only in operation until 1918.

Upon arriving to Mazuma, it’s easy to see just how unlucky of a place it was to build a town. Everything looks normal, until you start to realize that every uphill canyon for miles and miles does lead right to Mazuma’s doorstep. Even the recent rains have caused massive washouts—the dirt road is completely non-existent in some sections. We make a brief run over to the underwhelming ghost town of Ferrell, before turning toward town and counting our lucky stars that we managed to escape this trip without once becoming truly stuck in the mud.

GOLDILOCKS

I’ll leave you with the words of Author and Environmentalist Edward Abbey. His theory on the existence of desert water may be almost always correct, though I’m sure the unfortunate souls at Mazuma would disagree.

“Water, water, water…There is no shortage of water in the desert but exactly the right amount, a perfect ratio of water to rock, water to sand, insuring that wide free open, generous spacing among plants and animals, homes and towns and cities, which makes the arid West so different from any other part of the nation. There is no lack of water here unless you try to establish a city where no city should be.”