Nevada’s Only National Memorial

May – June 2019

A mysterious aircraft disaster outside Las Vegas hints that Nevada has been on the cutting edge of technology for decades—secretly.

BY KYRIL PLASKON

On Nov. 18, 1955, Las Vegans awoke to a fire near the very top of Mt. Charleston where there was not a scrap of wood to burn.

“Flame, just like there was a fire,” Henderson resident Lavern Hanks recalls. Her husband who worked for KLAS-TV tried to investigate. But men with rifles blocked the road to Kyle Canyon. So, he turned around and went home.

“My husband was followed all the way home by the FBI,” Hanks recalls. And when he walked in and she asked why he came home, he said the men with rifles threatened him: “You cross this line, and I will shoot you.”

“My husband was followed all the way home by the FBI,” Hanks recalls. And when he walked in and she asked why he came home, he said the men with rifles threatened him: “You cross this line, and I will shoot you.”

Hanks and everyone else around the nation eventually learned that it was a plane that had crashed in a violent storm the day before. What Hanks didn’t know was that her brother’s body was up there along with a dozen other men.

MEN IN BLACK

No one except the U.S. military, CIA, and FBI knew that the plane—a C-54 Skymaster USAF 9068—held the key to the biggest, baddest, and blackest of black projects that was being developed at Area 51 at the time. Key project personnel were on board and the CIA and FBI urgently needed to get there to secure classified materials.

Upon their arrival, park rangers told them that the snow was so deep it would be impossible to get there until spring.

That wasn’t an option.

The Air Force dispatched parachute teams to try to skydive in. The wind was so strong that the effort was abandoned. Then they tried a mountaineering team with skis and snowshoes. Only a few men made it in waist-deep snow and could do little more than secure the wreckage.

The military needed the expertise of Nevadans who knew these mountains, knew the routes, and had one resource the military didn’t have: horses. The selected group was the sheriff’s mounted posse, led by a man named Merle Frehner.

Frehner gathered a bunch of volunteers including his brother and a short, stout horse named Joe-Snip, also referred to as the “snow-buster.” The posse gathered at the Mt. Charleston Lodge and took inventory of their supplies. Some of the posse members wore high-visibility rescue jackets with black and white diamonds. The military men brought cans of Spam. The sheriff’s posse brought candy bars, sandwiches, cigarettes, and whiskey. Others carried no food at all.

“We figured we wouldn’t be gone long,” Sheriff Butch Leypoldt wrote of the plan to hike for 9 miles in waist-deep snow to an elevation of 11,000 feet.

BIG BROTHER

The Atomic Energy Commission—the agency tasked with assisting in the recovery—was not impressed with the plan and ordered the posse to stand down, expressing doubt that they would ever make it. But after the powers involved realized there was no other option, they gave the rough- and-tumble Nevadans the go-ahead.

The posse set out at 4 a.m. with 17 horses. The stout little pony Joe-Snip led the way through the drifts of snow. His head would move 2 feet to either side and his neck would push the powdered snow, breaking a trail.

“Man, there were times when the snow was so deep that we’d get off [our horse] and just hang on to the horse’s tail and let them pull us along on our bellies,” Leypoldt wrote.

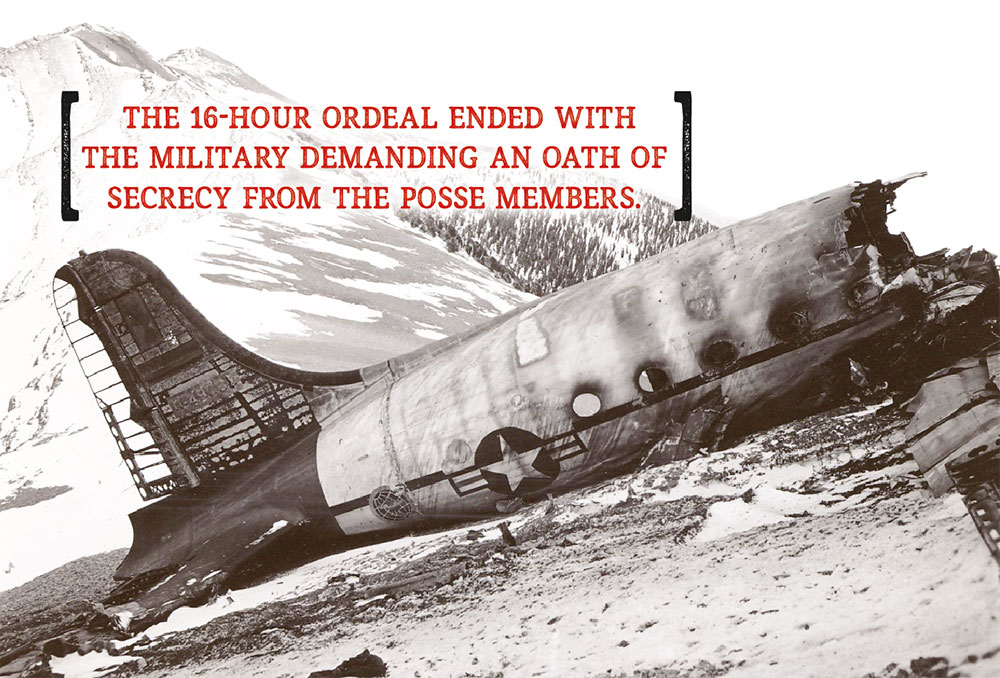

Some members of the party became sick and had to be carried down. Ice cut the horses’ legs, leaving a trail of blood. After 7 hours they reached the crash site. Debris was scattered 40-50 yards in all directions.

“The oddest thing was the co-pilot. He was laying on his back some 30 feet ahead of the plane, buried in the snow. He was wearing flying shoes, which were all that was visible and those shoes looked to be a yard long. He looked like a giant from a fairy tale,” wrote posse member Pat McDowell.

Air Force officers ordered the posse to wait while they secured classified materials and documented the rubble.

“Two Air Force colonels had ridden up with us,” Frehner wrote. “The freezing wind was blowing like 60 miles an hour. ‘We are going to freeze up here if we don’t get started going down the mountain and so will our horses,’” he said to the sheriff.

That prompted the sheriff to talk to the colonels and get started with the gruesome task of removing the bodies. The horses didn’t like the weather either and started bucking. One of the passengers was missing, but the posse didn’t have time to worry about that.

With the bodies on the backs of the horses, the posse would have to walk. They were on their own. The trail was frozen solid. Walking on chunks of snow was like walking on boulders.

“More than once, a horse would slip and roll down the slope, and we’d have to go down there and drag him back up onto the trail and start out again,” Frehner wrote.

The altitude made it hard to breathe and the men had to use shovels to clear the trail. Bodies fell off the horses and had to be left by the trail to be picked up later. In the black of night, the men began to stagger and fall.

“I drank what was left of the snake-bite medicine [whiskey]. It gave me a lift. I got hold of the horse’s tail and let her pull me along, but not for long,” Pat McDowell wrote. “It suddenly seems like my guts had fallen out and I couldn’t go another step.” He climbed on the back of his horse named Cindy, sat behind the dead body, and rode into camp at 8:20 p.m. The 16-hour ordeal ended with the military demanding an oath of secrecy from the posse members.

LOOSE ENDS

Military personnel fanned out across the United States and visited the families of the victims, bringing the message of their fate. In some cases, the message was a lie, or the military said pretty much nothing at all, just that their loved one was dead and one day the family would be proud of their work.

Behind the scenes, investigators put together a crash report detailing how the plane was blown off course due to high winds. The sign-out cover sheet for the classified crash report shows that few people ever looked at it. It doesn’t mention what kind of classified work the group was doing or that they were doing it at Area 51. The report was locked away and for all intents and purposes, that plane was officially still out there flying. According to the Military Aircraft Registry, USAF 9068 was not withdrawn from service until 1970.

New information came when a man hiked up to the crash site in September 1998. By then, the crash site was just a flattened pile of wires, pipes, and wheels. Standing over the wreckage in the silence, hiker Steven Ririe had a revelation that everyone on that plane had died and someone should find out who they were.

Ririe also found the one person who had been missing from the plane: Henderson resident Bob Murphy.

He was listed on the flight manifest, but it turns out he had slept through his alarm and missed the flight. He was the missing link, connecting the crash victims to the highly classified work they were doing at the time. The victims were CIA, FBI, and private contractors working on building the most high-tech intelligence project at the time: the top-secret, high-altitude-flying U-2 spy plane. These planes were credited with gathering critical intelligence during the Cold War and are still in use today.

Murphy says the crash paved the way for military contractors to require more experienced pilots. The crash also added to the urgency for more accurate weather data for flights.

Ririe tracked down the declassified crash report, and called the families of the victims, providing answers they had long sought.

Though he didn’t stop there. He reached out to legislators and politicians, telling everyone that this story needed to be told and preserved.

“At first, I didn’t pay any attention to him. His story sounded implausible” says U.S. Senator Harry Reid. “The more I talked to him, the more I realized that he was the one that was right and I was wrong. Some of them [victims] had no funerals. It is important that we recognize Cold War veterans who sacrificed so much and got no attention.”

It is speculated that thousands of Americans died like this in obscurity during the Cold War, victims of secrecy. But Ririe’s effort spreading this once untold story of military, FBI, and CIA victims, eventually convinced congress to approve the nation’s first Cold War National Memorial. It was dedicated in May 2015 at Spring Mountains Visitor Gateway at the base of Mt. Charleston, thousands of feet below where the plane crashed. The memorial features a twisted propeller from the crash site that Ririe removed himself with the help of volunteers.

CRASH SITE TODAY

The crash site of the C-54 is near 11,000 feet, where the air is so thin most trees can’t grow, and it’s as desolate today as it was in 1955. The remote location has mostly preserved the site.

“Back in the ‘50s, there were people who made it their job to go to these crash sites just for the aluminum,” says Dave Trojan, a 30-year wreck chaser who has surveyed more than 500 crash sites.

“I would say that only 10 percent of plane crashes are like this, where the whole airplane is there, just in pieces,” Trojan says. He calls his work “aircraft archeology” and sites like USAF 9068 are especially valuable.

“I reinvestigate these accidents and I believe that things can still be learned from them,” he says.

For instance, what proof is there that this was a top-secret military plane? The answer is in the wreckage.

Sitting among the gray rocks and bits of aluminum is a big bracket. Riveted to the bracket is a plate that says “U.S. PROPERTY MT-362A/A.” Through research, Trojan found that this bracket held the IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) system.

“It would have been very important on this aircraft and a must-have to be able to fly into Area 51,” he says. “This system would have allowed crews on the ground to identify if an approaching aircraft was a friend or foe. If it got into the wrong hands and put on an enemy plane, they could fly into the Area 51 airspace without raising alarms. Securing classified equipment like this was critical to the Air Force on that mission to the wreckage in 1955.

At the site, you can also view propellers, engines, wings, windows, controllers, air flow regulators, and internal communication devices.

“When you see the aircraft wreckage that is all opened up, you can see the engineering aspect, which is different than what you see at the museum. You get to see the internal working parts,” Trojan says. “That creates an appreciation for the engineering aspect that no longer exists in today’s aircraft.”

However, at the crash site, there is no identifying information. People who happen upon the site experience the same mystery Ririe did 20 years ago. Trojan says this would be a prime location for a metal post and sign.

“It helps the public so that they know what they are looking at and it helps prevent vandalism at the site,” he says.

Ririe says he hasn’t worked out the details with the Forest Service of where a sign identifying the crash could go, but this summer, he hopes to find himself on the final trek of this 20-year journey, hauling a sack of concrete, a post and sign up the mountain.

“That is probably the last piece of the puzzle,” he says.

For those who can’t make the trek up to the high elevation where the fateful crash took place, Nevada’s only national memorial whispers the story of these brave men who sacrificed everything for secrecy.