Michael Branch: For the love of the Great Basin

May – June 2020

Author hilariously recounts life in the lonely expanse of rural Nevada.

STORY BY TIM HAUSERMAN

PHOTOS BY MICHAEL BRANCH

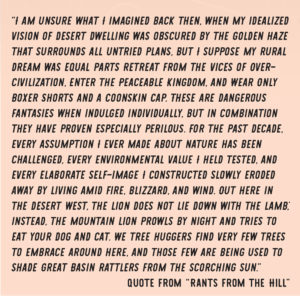

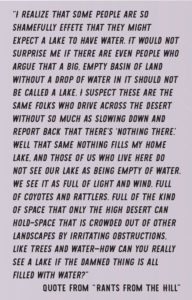

Most of Nevada is part of the Great Basin Desert—a massive, dry expanse of parallel mountain ranges and deep valleys covered in sagebrush, where you can drive miles without seeing much in the way of humanity. While some look at the vast desert as mileage that needs to be covered before reaching a destination, author and University of Nevada, Reno English Professor Michael Branch looks at what others consider nothingness as a place of complicated beauty that is waiting to be explored on foot. Branch has penned three books that chronicle the joys—and hilarious challenges—of his life living on the edge of the dry Nevada wilderness.

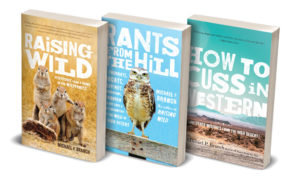

Michael’s Nevada trilogy includes “Raising Wild: Dispatches from a Home in the Wilderness;” “Rants from the Hill: On Packrats, Bobcats, Wildfires, Curmudgeons, a Drunken Mary Kay Lady, and Other Encounters with the Wild in the High Desert;” and “How to Cuss in Western.” The books chronicle his adventures with his two daughters and times of solitude in the desert about an hour north of Reno.

REALLY OUT THERE

REALLY OUT THERE

For several decades, Michael walked more than 1,000 miles each year within a 10-mile radius of his home. In the wide-open country, he often walked off trail, in every kind of condition from the heat of summer to the snows of winter, both day and night. All that walking gave him the chance to “get to know the land in way different ways than being a weekend warrior,” says Michael. “You see the land through all its different seasons. The more you cover the same ground, the more you learn to see it. The land changes and you change.”

His books—through a series of essays—focus on three main goals.

“We need to question the conventional standards of beauty,” Michael says. “The Great Basin feels alien to our definition of beauty, but it takes time to learn how to appreciate it. I’m hoping to help people understand a place they haven’t thought of as beautiful in a new way.”

Secondly, his stories often focus on a father introducing his daughters to the wilderness, and in so doing he hopes to expand the definition of nature writing, which has often focused on men alone in the wild.

“Wilderness is also a place for girls and families,” he says.

And finally, and perhaps most importantly to the reader, Michael believes that environmental writing is often about what we feel we are losing, instead of focusing on the great things we have. Instead Branch focuses on self-deprecating humor, which is apparent from the very beginning of his books.

“The humor often comes from the tension between a romantic sense of how rural life should be and the reality of how this land finds a way to humble you over and over,” Michael says.

“You fight for what you love, you love what you know, you know what you experience, and a book is one way to experience a landscape. Every book doesn’t have to say go out and fight for it,” he explains.

Michael heads out alone on long walks in his backyard for the solitude that can be found there.

“The world feels very noisy,” he says. “In the silence of the high desert you can hear yourself and hear the world. We develop more opportunities for thoughts to come to mind.”

WILD CHILD

WILD CHILD

While the importance of solitude is a main tenet of his writing, Branch feels his stories of children interacting with nature is equally important.

“Writing about children has been incredibly romanticized. It is not a pure joy to be with kids. It never goes the way it should go, and you have to roll with that. But I think it is vitally important that we get kids in wild places; we need to have a sense of humor that it doesn’t always work out the way you want it to,” he says.

Sharing the outdoors with kids can be a great learning experience not only for the kids, but adults as well.

“I have learned as much from my girls as they have from me. I developed a whole new sense of nature by sharing it with them. In these books I wanted to tell stories about what I have heard from them,” he says.

One of the most important lessons he learned from his kids is how to live in his place and in the moment.

A WALK ON THE WILD SIDE

A WALK ON THE WILD SIDE

I joined Branch on a walk through the sagebrush and rocky ridges near the home that is the centerpiece of his books. After driving a few miles on a rutty dirt road we stopped. On this beautiful sunny February day, there was absolute quiet and stillness. Over the next few hours as we tromped around the sagebrush, across marshy springs, and over little rocky outcroppings, the only interruption to that stillness was a half dozen pronghorns that galloped up a nearby hill. Branch seemed to be infinitely familiar and deeply in love with every rock, tree, and ridgeline within eyesight, and we quickly discussed a return trip to hike to the top of the highest ridge.

Michael is heartened to the reaction he has received from Nevadans to the books.

“The desert rats really like them. They say that someone is celebrating our landscape. There have not been too many writers who share the love for this place,” he says.

Taking a stroll with Michael Branch, I quickly learned he not only has a great love for the Great Basin wilderness, but he hopes to pass on that love and devotion—not only to his kids—but to anyone lucky enough to pick up one of his books.

Taking a stroll with Michael Branch, I quickly learned he not only has a great love for the Great Basin wilderness, but he hopes to pass on that love and devotion—not only to his kids—but to anyone lucky enough to pick up one of his books.