On the Sails of a Prairie Schooner

May – June 2020

The Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area protects America’s pioneer past and present.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

Imagine abandoning everything; rocketing steadfast into the great unknown. For the pioneer of the mid-1800s leaving life behind to verify whispers of gold out west, the scene must’ve been something spectacular. In many cases, the ordinary family farm wagon was modified for the trip: hickory bows were affixed to the wagon bed and a canvas cloth was stretched over the top, iron was attached to reinforce the wagon’s most vulnerable parts (wheels, axles, and tongue), and a bucket filled with mixed tar and tallow (animal fat) used to lubricate the axles was affixed to the wagon’s rear.

The wagons in those days became known as prairie schooners, due to the cover’s resemblance to a boat’s sail. A team of animals, usually oxen or mules, pulled these wagons across 2,000 miles or more of infinite plains, parched deserts, and mutinous craggy cliffs.

One such stretch of the historic trail to the California gold fields, known as the Applegate-Lassen Trail, traversed a 130-mile section spanning from Lassens Meadow (now Rye Patch Reservoir) to its exit west of Vya in Nevada’s northwestern corner. Many of the trail’s most historic sites exist today within the protected Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area—an 800,000-acre swath of land that contains untamed wilderness areas, spectacular geological formations, and an endless nod to America’s pioneer past.

The region was traversed and explored extensively by the pioneers of yesterday, but its wild nature and remote location gives today’s “pioneers” a chance to see, feel, and experience many aspects just as they were so long ago.

BLACK ROCK DESERT

Yesterday’s Pioneer: As magnificent as this spectacular scene on the Applegate-Lassen trail was at times, it was sometimes equally sinister. On the southeastern side of the National Conservation Area lies the mighty Black Rock Desert. The desert is one of the most notable dry remnants of Lake Lahontan—a massive ancient lake that covered much of northwestern Nevada around 12,000 years ago. At the time of the pioneer’s crossing, the vast alkali expanses created a flat, easy surface to navigate, though the waterless trek across the desert from Rabbithole Springs to Black Rock Springs proved to be a formidable section of the trail.

“I shall never forget that night march. The road was lined on both sides with carcasses of animals which had perished on the way. They were so thick that from the Wells to Black Rock by stepping from one body to another one need never to have touched the ground.”

These words were written by a pioneer describing the stretch of trail across the Black Rock Desert. They give a glimpse into the sights, sounds, and smells pioneers experienced while traversing the region. If a wagon was resilient enough to survive the trip across the Black Rock to Black Rock Springs, the difficulties continued as they headed north past Mud Meadows and into the famous Fly Canyon.

Today’s Pioneer: Though the playa at the Black Rock Desert can now be crossed in a vehicle instead of a team of oxen, the undeniably beautiful yet sometimes ominous nature of the region reminds visitors that the dangers in this remote part of the state are still as real as ever. The absolute vastness of the area finds no justice in written words; it must be experienced firsthand to truly understand. Each year, people are lured in by the playa’s seductive charm, thinking they can simply drive across it at any time during the year.

This is not the case.

Even a slightly wet playa can turn into the sloppiest, soupiest alkali muck one has ever encountered, swallowing lifted Jeeps and trucks above the axles in a heartbeat. Many an unsuspecting modern pioneer has been stuck and probably left wondering why a cement truck would drop its payload in such a strange place, and equally wondering which helicopter company they can hire to get them unstuck.

FLY CANYON

Yesterday’s Pioneer: As emigrants made their way north past Mud Meadows and into modern-day Soldier Meadows, they passed near the U.S. Army fort named Camp McGarry. The camp was manned from 1865-68, and was established to protect mail and stage roads, as well as the pioneers traveling west. The main camp was located about 12 miles north of Soldier Meadows (on what is now the Summit Lake Indian Reservation), but the Army constructed officers’ quarters, mess hall, barracks, and a 100-horse stone barn at Soldier Meadows, and would move operations there during the winter, due to the lower elevation and nearby hot springs.

From Soldier Meadows, the wagons headed west toward Fly Canyon, where they would encounter another major obstacle, one that left wagons in splinters and emigrants stranded without means to carry on. The Fly Canyon wagon slide, as it came to be known, was an especially steep section of trail that required technical navigation, testing and taunting the stress levels of humans, animals, and equipment. Pioneers would lock the wheels, tie the wagon off to the oxen with ropes, and slowly lower them down the 45-degree slope. A plaque at the wagon slide, words spelled exactly how they were in a pioneer’s diary, reads, “Had some verry stony rodes. One hill locked both wheels & put on ropes to let our wagons down. All got down safe. Saw some handsum sights along the rocks. Holes maid buy the wind.” —Abram Minges, Aug. 17, 1849.

Today’s Pioneer: Modern pioneers can drive Soldier Meadows Road north, close to the route where yesterday’s pioneers traveled. Remnants of officers’ quarters, mess hall, barracks, and a 100-horse stone barn at Soldier Meadows still stand, though they are located on private property. The property is owned by Soldier Meadows Guest Ranch—a remote bed & breakfast that is, unfortunately, closed indefinitely.

Evidence of covered wagons traversing the wagon slide can still be seen today. To the unexpecting eye, the slide looks like nothing more than a light-colored hill; steep yet only a couple dozen feet tall. Yet, when imagining a wooden wagon holding several thousand pounds of supplies being lowered down by oxen and ropes, one could see how difficult and worrisome a task this must have been.

The spectacular “holes” described by Minges rest in Fly Canyon just northeast of the wagon slide. The holes were created during the last 11,800 years, after a massive rockslide blocked the natural water outlets through nearby High Rock Canyon and Little High Rock Canyon. With no place to go, the water formed the new Fly Canyon, and the constant whirlpool action of sand and gravel in the stream caused almost perfectly cylindrical potholes—called a giant’s kettle—to form in many places in the canyon. The giant’s kettles in Fly Canyon range in size from up to 10-feet in diameter, and in some cases are believed to be several dozen feet deep. Modern pioneers can access Fly Canyon to view the potholes; however, extreme caution should be exercised, as the area is dangerous in places, and rock-climbing gear and skills are required to traverse past the first 200 yards or so.

HIGH ROCK CANYON

Yesterday’s Pioneer: After successfully lowering their wagons down the steep slide at Fly Canyon, emigrants continued on through one of the most scenic and important milestones of the trip: High Rock Canyon. More than 10,000 wagons are believed to have passed through the canyon in 1849, and the section of trail is one of the most written about by those who laid eyes upon it in those days.

“On both sides, the mountains showed often stupendous and curious-looking rocks, which at several places so narrowed the valley, that scarcely a pass was left for the camp. It was a singular place to travel through—shut up in the earth, a sort of chasm, the little strip of grass under our feet, the rough walls of bare rock on either hand, and the narrow strip of sky above. The grass to-night was abundant and we encamped in high spirits.” —Explorer John C. Fremont, Dec. 30, 1843.

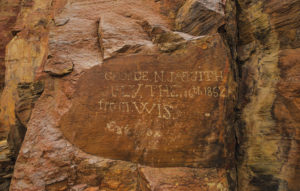

The canyon acted as an oasis for the pioneers that would follow Fremont. Vegetation was plentiful, and the colorful canyon walls and volcanic tablelands provided a scenic respite to the often dull sections of the journey. In this canyon, several pioneers left their mark upon the walls and in caves, probably never imagining that their story would continue to be told so many years later.

Today’s Pioneer: Aside from the rocky road that winds its way amid the canyon walls, visitors of High Rock Canyon are afforded the same views as Fremont in 1843. The walls appear as if they were painted by artists with overly colorful palates. Wildlife including bighorn sheep, deer, antelope, and chukar are plentiful in this pristine place, and pools throughout the area contain fish that are descendants of those that called ancient Lake Lahontan home. The road can be explored on foot, mountain bike, or 4-wheel-drive vehicle, though a seasonal closure is in place each year from around February to mid-May in order to protect nesting raptors and lambing bighorns. Vehicles and mountain bikes are not allowed to stray from the main road through the canyon, however. High Rock Canyon, along with most of the surrounding area, is a designated wilderness area, meaning only foot traffic is allowed anywhere except for the main road.

Though not a route typically traveled by the pioneers, Little High Rock Canyon—located to the south—offers similar scenes and solitude. Little High Rock Canyon is also a protected wilderness area—again only foot traffic is allowed. While no designated hiking trails exist in the canyon, hikers can enter the canyon either at the mouth or the rim. Trekking is extremely difficult by both entrances, but the views are well worth it.

FORTYNINE & BEYOND

Yesterday’s Pioneer: After exiting the scenic High Rock Canyon, emigrants made their way north and then west, as they climbed from the canyon and traveled across high-desert plains. One notable feature in this largely dull section was Bruff’s Singular Rock, a rock outcropping made famous by a sketch in the diary of pioneer J. Goldsborough Bruff.

As pioneers made their way across Long Valley and toward Fortynine Mountain (now on the Nevada-California border), they were greeted, albeit unpleasantly, by Fortynine Lake. Fortynine Lake proved to be undrinkable, though nearby Fortynine Spring (near Vya) gave welcomed water after a 20-mile dry stretch.

Wagons climbed through Fortynine Pass and made their way into the Surprise Valley of California, before either heading toward the California gold fields to the south, or north into Oregon.

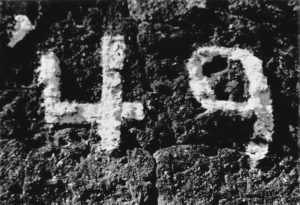

One notable greeting to the Fortynine area, appropriately, is a large “49” painted onto a rock in the canyon by pioneers passing through. Originally drawn using axle grease, the numbers have been painted over so many times since then, that the paint protrudes an inch from the rock.

Today’s Pioneer: Roads take modern adventurers north out of High Rock Canyon, skirting the trail’s route all the way to California. Stevens Camp, located several miles north of High Rock Canyon, is a recreational cabin open year-round to public use, providing a modern oasis in the desert. Roads take travelers all the way to Vya, where the Old Yella Dog Ranch provides guests a ranch lodging experience in one of the most remote parts of the state. From there, Fortynine Pass climbs up toward the border, where modern pioneers can peer down upon Surprise Valley in California.

TAR AND TALLOW

Imagine again abandoning everything; rocketing steadfast into the great unknown; conquering sickness, disease, death, failed equipment, steep terrain, miles of dry barrenness, and months of grueling travel. Every day was a test of character and wits.

Imagine the feeling they must have felt as they descended Fortynine Pass and finally laid eyes upon California—a then almost magical place that many considered to be the promised land. Though we’ll never truly know how it must have felt, we should feel lucky that us modern day pioneers can still experience a taste of such a pristine and sacred land. And thanks to those that respect and protect these great lands, generations that come after us will share the same experience.

Let’s keep it that way.

EXPLORE MORE

Friends of Black Rock-High Rock

320 Main Street

P.O. Box 224

Gerlach, NV 89412

blackrockdesert.org, 775-557-2900