The Ballad of Diamondfield Jack

May – June 2020

The story of a hired gun, murder suspect, and mining magnate.

BY RON SOODALTER

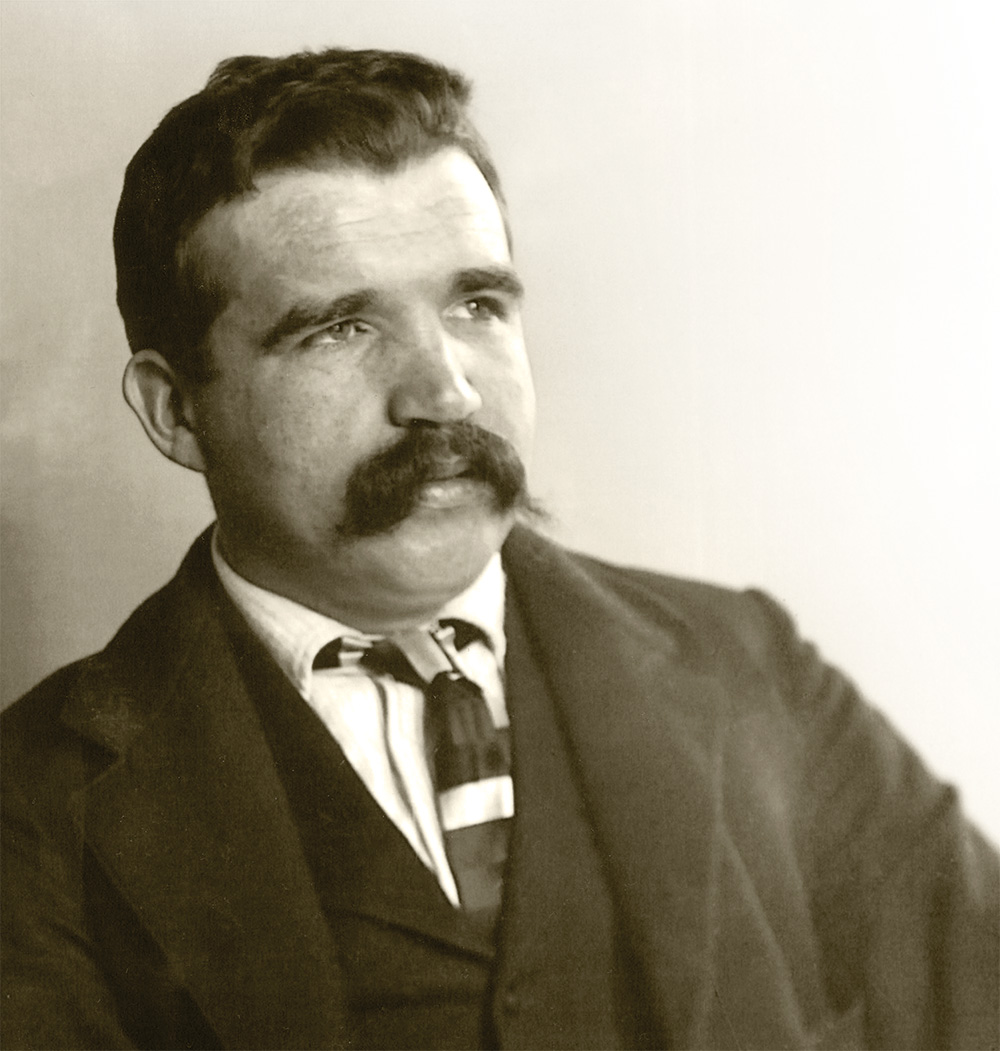

To the cattlemen on the Nevada/Idaho frontier of the 1890s, sheepherders were anathema. So virulent was the feeling against them that the owners of the vast Sparks-Harrell Cattle Company of northern Nevada and southern Idaho hired a man to rid their range of sheepmen. His name was Jackson Lee Davis, and his brief tenure as a hired gun was but one facet in the life of this unusual man. By the time of his death, Jack Davis had established himself as a thoroughgoing legend of the western frontier.

Despite the Hollywood version of cattle raising in the Old West, few ranchers employed a gun-for-hire to eliminate rustlers or sheepherders. This is not to say it wasn’t done; around 1895, a few of the larger spreads in Wyoming brought in a “regulator” named Tom Horn to “clean up” the range, and at $500 a head, he was well on his way to doing so when he was convicted of murder and sent to the gallows. For years, Jack Davis faced the likelihood of the same fate.

Jack’s early years are shrouded in mystery. Depending on which publication one reads, the year of his birth ranges from 1863 to 1879. Idaho prison and newspaper records list his birthdate as 1871; his gravestone reads 1864.

Of certain facts, however, we can be sure. In the early 1890s, Jack was working in the Black Jack Mine, near the boomtown of Silver City, Idaho. When word spread that diamonds had been discovered, Jack quit the mine to prospect for the precious stones. Although it proved to be fruitless, he had talked so much about making his fortune in the diamond fields that people began calling him “Diamondfield Jack.” He was a habitual braggart and his inclination to boast—what one biographer referred to as his “periodic propensity for exaggeration and distortion”—was destined to get him into serious trouble.

THE REGULATOR

By 1895, Jack had worked as a cowboy on various ranches in Nevada and Idaho, before hiring onto the Sparks-Harrell Cattle Company. The company’s owners—assuming it would be acceptable to cattlemen and sheepherders alike—had earlier established a “do-not-cross” line, dividing the grazing range between cattle and sheep. However, when the sheepmen consistently ignored the line, the cattlemen ordered Jack to “keep the sheep back.” He was reportedly ordered not to kill, but to strongly discourage the interloping herders, wounding them if necessary.

By 1895, Jack had worked as a cowboy on various ranches in Nevada and Idaho, before hiring onto the Sparks-Harrell Cattle Company. The company’s owners—assuming it would be acceptable to cattlemen and sheepherders alike—had earlier established a “do-not-cross” line, dividing the grazing range between cattle and sheep. However, when the sheepmen consistently ignored the line, the cattlemen ordered Jack to “keep the sheep back.” He was reportedly ordered not to kill, but to strongly discourage the interloping herders, wounding them if necessary.

Jack visited a number of sheep camps, talking tough and displaying his guns. He fired into at least one camp and wounded one of the herders in a quarrel. Fearing a murder charge should the man die, he fled across the state line and took refuge in Wells. While there, he constantly boasted of his status as a killer-for-hire and claimed to be earning three times his actual salary. The wounded sheepman survived, and the following year Jack returned to Idaho and his employers at Sparks-Harrell.

He would have done better to remain in Nevada. In February 1896, two young sheepmen were found shot to death in their wagon, and suspicion fell on Diamondfield Jack. He insisted he was innocent; however, with public opinion overwhelmingly against him, formal charges were brought and Jack—along with a cohort—bolted for the Mexican border with a $5,000 bounty on his head. They were captured in Yuma, Arizona, and returned to Idaho for trial.

TRIAL AND APPEALS

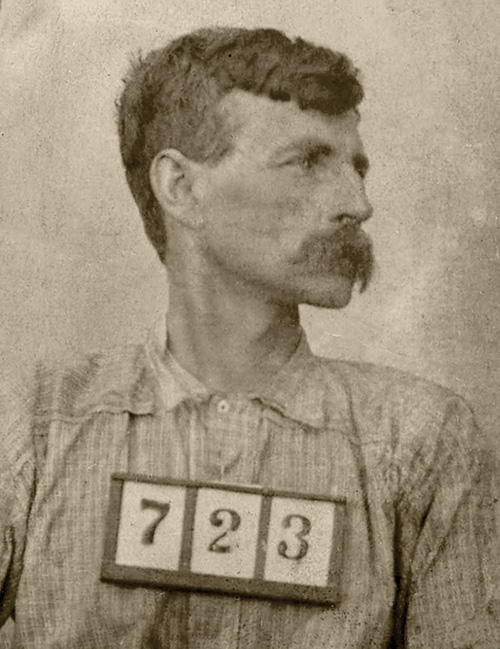

After deliberating for only two hours, the jury found Jack guilty and he was sentenced to hang on June 4, 1897. Ironically his cohort, who was later tried on the same evidence, was acquitted. Jack’s lawyers immediately filed for a retrial, but both the local judge and the state supreme court turned him down. As the appeals process slowly traveled through the courts, Jack’s appointed date with the hangman was twice rescheduled.

Then in October 1898, two men confessed to the killings, claiming self-defense. One was the Sparks-Harrell Cattle Company’s general superintendent. They stated they were attempting to drive the two young herders from the range when a fight broke out, leaving the two sheepmen dead.

Their story was highly probable, especially because John Sparks—co-owner of Sparks-Harrell—confirmed it. However, because the two men had lied to protect themselves during Jack’s trial, their confessions were thrown out. A third date was set for Jack’s hanging.

In light of the recent confessions, popular opinion had begun to shift in Jack’s favor, but the request for a pardon was still refused. The case then went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to interfere in the original decision. Yet another date was set for the execution: July 3, 1901. Jack had seen in a new century as he sat in his prison cell, braiding horsehair and waiting to die.

Jack’s lawyer again made a last-minute appeal, resulting in a commutation to life imprisonment. The news reached Jack just hours before he was to hang.

The wheels of justice were finally turning Jack’s way, due in large part to public opinion. In late December 1902, under pressure from several highly-placed individuals—including John Sparks, who was now governor of Nevada—the Board of Pardons granted Jack a full pardon. Technically, his earlier conviction stood, but at least he was a free man.

HITTING IT BIG IN NEVADA

Diamondfield Jack had spent nearly seven years in prison, for a crime of which he was almost certainly innocent. According to one of his biographers, “[H]is death sentence was suspended, reprieved, or stayed seven times….” Upon his release, he left Idaho, and there is no indication he ever went back.

If leaving Nevada years earlier was a poor decision, returning to it proved an inspired move. Jack’s release coincided with the recent discovery of gold and silver and he gravitated to the aptly-named new town of Goldfield. The marriage between the boomtown and the colorful ex-convict was nothing less than inspired. Although physically a small man, both his reputation and his larger-than-life personality made him a perfect fit for the wide-open community. He had lost none of his bravado; a photograph of the period shows him holding a shotgun in his right hand, while his left is drawing a Colt revolver, with a second pistol in his belt.

If leaving Nevada years earlier was a poor decision, returning to it proved an inspired move. Jack’s release coincided with the recent discovery of gold and silver and he gravitated to the aptly-named new town of Goldfield. The marriage between the boomtown and the colorful ex-convict was nothing less than inspired. Although physically a small man, both his reputation and his larger-than-life personality made him a perfect fit for the wide-open community. He had lost none of his bravado; a photograph of the period shows him holding a shotgun in his right hand, while his left is drawing a Colt revolver, with a second pistol in his belt.

With grubstake money presumably from friends, Jack immediately got busy. He invested in mining claims, bought property, and formed several lucrative partnerships. Everywhere he went, the local papers touted the activities of the legendary “Diamondfield Jack.” About a year following his release, an article appeared in the Baker, Oregon, “Statesman,” titled, “He Has Struck it Rich: ‘Diamondfield Jack’ Davis Wins Fortune’s Smile.” It goes on, “Jack Davis, famous throughout the west as ‘Diamondfield Jack,’ after a strenuous career as a border fighter, diamond detective and a convicted murderer under sentence of death, struck it rich in Goldfield….”

Soon, boomtowns were being named for and by him, and he became mayor of newly-minted Diamondfield City. In addition to discovering gold, silver, and lead, he also found a wife. The San Francisco “Call” wrote “ ‘Diamondfield Jack,’ once a cowboy, next a doomed convict, then a poor prospector, is a mining magnate and now a happy husband.” The union was brief, however, and ended acrimoniously.

Jack was as generous with his friends as he was bombastic and was referred to in a local paper as “one of the richest and most generous-hearted of Nevada’s miners.” He was also no stranger to violence. He served on at least two posses in pursuit of fugitive killers, and singlehandedly stood off a 300-man mob when they attempted to lynch two young members of a local union. On another occasion, Jack fought off two would-be assassins from the Industrial Workers of the World, with whom he’d been involved in a years-long feud. As he stabbed one, another shot him in the jaw before fleeing.

ENDINGS

ENDINGS

Eventually, Jack’s luck turned, and he lost his fortune. Still, the newspapers occasionally carried stories about him, often printing wild and totally fabricated accounts of his dramatic death. When the end finally came in early 1949, it was the result of being struck by a Las Vegas taxi.

Not surprisingly, the newspaper obituaries were a compendium of exaggerations and misstatements. Perhaps the most appropriate description of the man was one written 20 years before his death, in the Tonopah “Daily Times-Bonanza.”

“Jack Davis, ‘Diamondfield Jack,’ one of the pioneer boomers of Tonopah and Goldfield, bad man, good man, prospector, and a man of fortune and misfortune….”

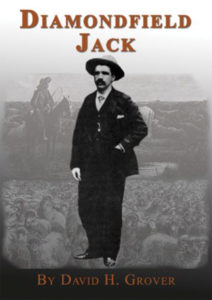

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading