Yesterday: A Woman of Breeding

May – June 2020

Molly Flagg Knudtsen gave up the good life for the great life—raising cows on her ranch near Austin.

This story first appeared in the September/October issue of Nevada Magazine.

This story first appeared in the September/October issue of Nevada Magazine.

By ALICE M. GOOD

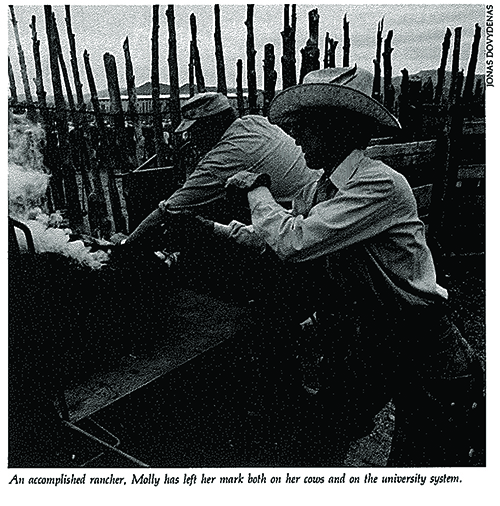

The slender woman wipes the blood off her knife with a sponge and waits for the three cowhands to bring another calf down the chute and wrestle it onto her worktable. Moving with an efficiency that comes from long practice, she vaccinates and brands each calf. Then she does the knife work. She cuts a mark on the ears of each calf so she11 know her stock when winter hair covers the brands. She works quickly, easily keeping ahead of the men. The heifers take only a minute; the steers take a little longer-they have to be castrated.

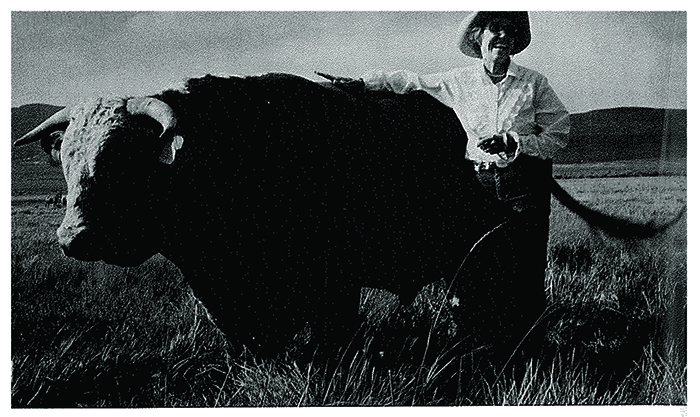

Last year Molly Flagg Knudtsen branded 867 calves on her 9 ,000-acre Grass Valley Ranch. That’s rough work for a former debutante.

Running a cattle ranch in Central Nevada might seem a strange occupation for a woman who was raised in riches. Her explanation, straight as a buckaroo’s hat brim, is laced with a cultured British accent that dates from her days at Miss Spaulding’, School for Girls.

“I could have lain on a couch all my life like Madame Recamier, but I wanted to contribute to my new state and to help young people who didn’t have the advantages I had as a youngster.”

So, besides wrestling stock at her ranch, she’s been known to tangle with politicians in board rooms across the state, lobbying for funding for academics in her role as university regent. She’s led students on archaeological trips into the remote reaches of Central Nevada, and her fascination with Nevada’s previous civilizations also is evident in the two books she has written.

Her transition from socialite to rancher began in the early 1940s when she came to Nevada to help train race horses on a friend’s ranch in Reno. While there, she also took advantage of the state’s six-week residency law to obtain a divorce. She dismisses that episode casually, saying that even though the marriage lasted a few years, the memory of it is vague.

Her transition from socialite to rancher began in the early 1940s when she came to Nevada to help train race horses on a friend’s ranch in Reno. While there, she also took advantage of the state’s six-week residency law to obtain a divorce. She dismisses that episode casually, saying that even though the marriage lasted a few years, the memory of it is vague.

While in Reno, the subtle beauty of the desert grew on her. And so she adopted the state with the same maternalism she showers on her “little girls,” the cows on the Grass Valley Ranch.

Her move to Nevada surprised her eastern friends and relations. “She had an extremely privileged upbringing,” says John Pierrepoint, a childhood friend from another New England blue-blood family who visits her occasionally. “Molly was vaguely dissatisfied with her life as an eastern socialite. We were shocked when she decided to live in the deserts of Nevada, but I think she was really searching for some kind of fulfillment and accomplishment in her life. She seems to have found it in Nevada.”

Molly Flagg was the only child of an heiress and an architect. Her father died when she was seven, and her mother married a U.S. Army colonel. He took his new family and governess to the ancient hills of Rome, the sand dunes of Abu Sambel, and the dew ponds of Southern England. They had homes in the well-heeled neighborhoods of Long Island, New Jersey, and Florida.

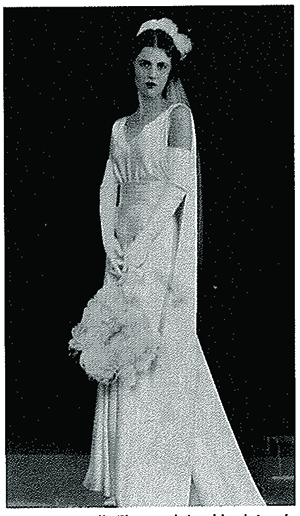

As a pampered little girl, she once bit her horse in a fit of temper. As a cultured young woman, she made her debut before the king and queen of England at the Court of St. James in the late ’30s. A sense of obligation to community, learned from her military stepfather, was nurtured in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. There, in her late teens, she did volunteer work for six months with critically ill patients and their families. Her love of horses and adventure drew her into the first of several male arenasthe inter’national horse circuit. As a child Molly had watched her stepfather ride his own horse in the Grand National; in her early 20s she became one of three licensed women horse trainers in America.

During her first Nevada stay on that ranch in Reno, while she was preparing to race horses in California, she met Dick Magee, a wildly attractive Irishman 15 years her senior who had a penchant for unpredictability and liquor. (It’s said he once rode his horse into the bar of Reno’s Riverside Hotel.) His Princeton background and indulgence in race horses matched Molly’s Foxcroft finishing school elan. They were married in Fallon in 1942, and Molly went to live on his Grass Valley Ranch, 26 miles northeast of Austin.

“She won’t last six months,” Magee’s doting mother said about his impetuous bride. But Molly stuck it out. While Magee trained thoroughbreds on ranch racetracks, she rode her horse sidesaddle as she had with her French riding master in the parks of the Trianon Palace. Neighbors traveled 20 miles to see her fall off. She never did.

During those first few years on the ranch, Molly plunged into Nevada history with typical drive and determination. “I read everything about Nevada I could get my hands on,” she says. “I was desperately trying to understand where I was.”

She rode her horse from one end of Grass Valley to the other, learning about the men and women who lived there during the thousands of years before the coming of white men. In her wanderings, she noticed an alarming situation. “I grew concerned about the churches, the old churches of Austin, which had been abandoned,” says Molly, who admits she is not particularly religious. “I was horrified to see them crumbled to ruin and worried about the young people and the future of their institutions, including the schools.” So she helped in a restoration effort that put a new roof on St. George’s Episcopal Church, and she donated a Steuben cross for the altar. Soon St. George’s was flourishing, and other churches began to revive.

Molly and Dick had a son, Bill, who is now a stockbroker in Dallas with two small boys of his own. It was a rocky beginning for mother and son. He was a sickly child, and Magee’s mother took him to live in San Mateo, California. “It wasn’t as though I gave him up,” Molly says, ”but once he was there, I couldn’t get him back. He would raise such a fuss when I tried to take him from his grandmother that I let him stay.”

Molly’s son never did live on the Grass Valley Ranch. “I wish I had grown up with my mother,” Bill says, “and at one time in my life it was an issue. But I know she cares a lot about me and we now have a great relationship. She’s helped me immeasurably in the things I’ve accomplished in my life. We’re friends as well as mother and son.”

With no child to rear, Molly turned her attentions to the ranch. In her childhood travels she had observed livestock in the Hebrides and the Sudan. She had seen the sacred cows of India dozing in the streets of Bombay and cattle on the slopes of the Pyrenees worked by the Basques. Her love of animals, nourished during her race horse period, was brought out on the isolated ranch.

“You find no shortage of people who like horses, but there seems to be an aversion to loving something that will be eaten,” Molly says. “I happen to like cows.”

The first 26 years she lived at the ranch, no buckaroo was hired. She doctored, branded, gathered, and worked the 2,500 head of cattle, trying to breed a commercially successful line of straight-bred Herefords. When she started, only three out of 10 cows were giving birth, and the calves averaged only 350 pounds. Now nine of 10 cows give birth, and the calves average 500 pounds, an astounding accomplishment.

“Molly does what other people talk about, like culling,” prominent Texas Hereford breeder Doug Bennett says of her ability to spot and eliminate weaker cows from the herd. He knows Molly’s expertise well since he sells bulls to her and buys cattle from her, too. “She’s a tough businesswoman,” he adds.

“Molly does what other people talk about, like culling,” prominent Texas Hereford breeder Doug Bennett says of her ability to spot and eliminate weaker cows from the herd. He knows Molly’s expertise well since he sells bulls to her and buys cattle from her, too. “She’s a tough businesswoman,” he adds.

Molly’s tangles with livestock are legendary. Last year, after a joust with a 2,600-pound bull had spll t her shin, she returned to Grass Valley from the hospital on crutches. As she passed the field of yearling purebred heifers, kept inviolate for breeding to a worthy registered bull, she saw smiles on their brown-and-white faces. In their midst was an amorous bull from the University of Nevada’s Gund Ranch, which is nearby. The bull had broken through the fence like a fraternity boy on a pantie raid.

“I threw away my crutches, sprang on my horse, and drove that bull from paradise 20 miles to the Gund Ranch. Those naughty ladies are enough to drive me mad!” she laughs.

Molly’s work in churches and schools, with the university’s herds and with archaeological relics put her in contact with people and educators around the state. She thought she saw inequality in school districts and was concerned about the kind of education that rural youth were getting. While she considered running for the local school board, some urged her in 1960 to try for the university system’s Board of Regents. In those days it was a male-and Las Vegas dominated board to which no woman had ever been elected.

“They told me, ‘You can’t have a woman on the board,”‘ Molly recalls. “Well,at that time there were 800 women students. I’ve never been a feminist, but that kind of challenge was just what I needed to spur me on. I had done things all my life that women weren’t supposed to do.”

With the slogan “Molly Magee for District Three,” she campaigned on the platform “You need a woman on the Board of Regents.” She crisscrossed the state’s rural counties from Panaca to Denio and carried more parade flags than a National Guard private. But this was familiar ground, for she had ridden in New York parades with her stepfather, who had once been a deputy chief of police. Molly Magee won the election by a landslide and remained on the board for 18 years until her retirement in 1980, when she declined to run for a fourth term.

“She was one of the best regents the university ever had,” says Dr. Fred Anderson, a longtime former regent from Reno who remembers carryjng her up the stairs to meetings after ranch accidents had shattered her knee caps and bruised her face.

In the lion’s den she spoke her mind. Author Robert Laxalt says, “She never went for political expediency. She voted for what was right.” Laxalt came to know Molly as one of the early supporters of the effort to establish the University of Nevada Press. Her background in printing dates back to her grandfather, who in the late 1800s patented the Hoe Printing Press, which remained the standard press for newspapers for half a century.

“Molly has a mind like an academician. She knows what a university should be,” says sociologist Jim Richardson, who, as chairman of the powerful UNR Faculty Senate during the turbulent ’60s, opposed her on many issues. 11She would sometimes treat us like a mother hen and bawl us out like she does the cows on her ranch, but she always listened fairly and understood the concerns of the faculty and the students.”

Molly’s work in helping establish the UNR Department of Anthropology and the Desert Research Institute earned her an honorary doctorate of science. She is still active as chairman of the College of Agriculture’s Citizens Advisory Committee and as a Friend of the University Press.

But while Molly played regent and rancher, Dick Magee took his thoroughbreds to California to race. One day in 1967 he didn”t come back. “That was a lonely time in my life,” she admits. “He told me I couldn’t make the ranch work. It was a good thing he said that, because I did.”

Shortly thereafter, a tall, drawling horse trader, Bill Knudtsen, came to Grass Valley to gather up horses. He stayed all winter, and the reason was Molly. They were married on Easter Sunday in 1968. “It’s been a happy marriage,” says Molly. “If I had looked the world over, I would have never found anybody better for me or the ranch.”

“She’s the best damn cowman I’ve ever seen,” reciprocates Bill.

Does she have advice to young women working in male provinces?

“Pin a rose behind your ear. When you’re in a difficult situation, be a storyteller like Scheherazade. Have a sense of humor. Get along. Be sure of yourself, but always be a woman.”

Now “solidly in my 60s,” Molly looks forward to future challenges in cattle breeding and in educating young people. “It’s important to open new vistas, to be creative, to have ideas,” she says.

In her 1975 book “Here is Our Valley,” which was republished in 1985 by the College of Agriculture, she recounts tales of the “men and women … whose names are still remembered in the valley … they too left their mark not easily seen, not always recognized, and yet indelibly stamped on Grass Valley.”

The same could be said for Molly Knudtsen.