The Dann Sisters: Searching for Reciprocity for the Western Shoshone

November – December 2015

Discover the quest of two sisters to recover their homeland.

By KATHIE TAYLOR

Carrie Dann—an elder in the Western Shoshone Nation—goes into the mountains surrounding her Crescent Valley home one afternoon in search of pine nuts, a traditional Shoshone food. A successful hunt for pine nuts might seem like a foodie’s dream, yet for Carrie it is the gift of Mother Earth for which she will reciprocate with prayers and thanks, as is the lifeway of the Western Shoshone people.

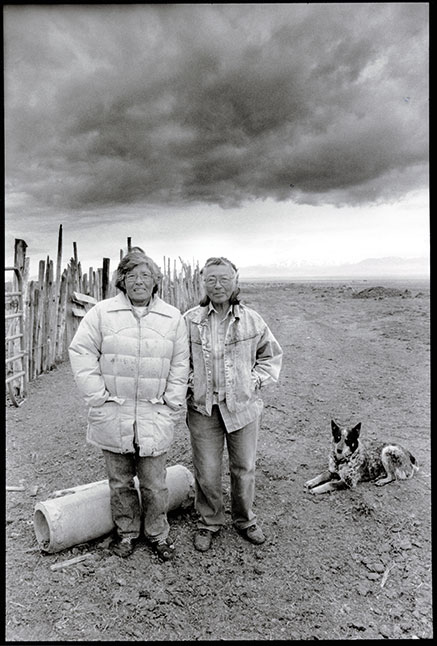

The Shoshone believe in reciprocity: what is taken from the Earth must be replaced. For the Dann family, nothing can replace their horses and cattle rounded up on three separate occasions by the Bureau of Land Management for non-payment of grazing fees, nor for the 50 years that Carrie and her sister, Mary, devoted to advocating for the return of ancestral lands and Shoshone sovereignty.

FIGHTING FOR THEIR RIGHTS

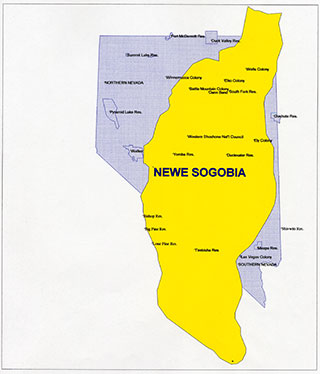

But according to the Western Shoshone National Council, the government never produced any documentation signed by the Nation giving up rights and control of the lands. Known to the Shoshone as Newe Sogobia, these lands encompass millions of acres across Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and California.Carrie, now in her eighties, is the surviving sister of the legendary Dann sisters—two Western Shoshone elders who fought a legal battle for grazing rights against the United States government for more than five decades. At the heart of the fight is the Dann sisters’ position that the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley granted peaceful passage for settlers across the ancestral lands of the Western Shoshone but did not cede the land to the United States. In the 1970s, the Indian Claims Commission—citing “gradual encroachment”—awarded the Shoshone Nation $26 million in an attempt to settle the issue.

Because the Nation did not accept the money, it sat undisturbed until the Western Shoshone Claims Distribution Act of 2004 became law, authorizing payment of the funds now totaling $145 million with accrued interest to members of the Nation. Again, the Western Shoshone National Council disputed the claim to its ancestral lands because no member of the Nation signed the document.

“Some Western Shoshone refused to take money over the principal of the issues,” says Mary Gibson, a cousin of the Danns. Mary is also the archivist of the Dann sisters’ legal battle documentation. “It is against traditional values to take money for land that, according to the Shoshone belief system, cannot be owned. Traditional thinkers were still hoping for fair treatment to reclaim as much, or at least some, of their ancestral lands.”

“Many young people are not connected to the land or to our history,” she says. “We are foreigners in our land.”Mary says her children accepted the money, but she did not.

TEACHING LIFEWAYS

Raised by her grandparents who were ranchers on the federal land trust at the Odgers Ranch Indian Reservation while her mother went to nursing school in Elko, Mary spent many hours listening to the stories her grandmother told.

“My grandmother was an advocate of land and treaty rights, a real modern day activist of her time,” Mary says. “Carrie was young [then] and she could drive. That’s how it was. You would sit and listen until you learned the issues, and only then, you talk. They traveled together to meetings with other traditionally minded people fighting for the same issues.”

Mary moved to Elko with her mother when she started kindergarten, but continued to spend many weekends and summers at the Dann ranch.

Carrie and her sister Mary Dann gave Mary Gibson her foundation in the spiritual and philosophical view of Shoshone lifeways. Mary Dann was the matriarch of the family ranching operation and Carrie was the philosopher and political activist.

“Mary would give sound advice,” Mary says. “She was kind and gentle. Everyone leaned on her even though she didn’t say very much. She felt the same about carrying on in the way of the Shoshone; she just expressed it differently than Carrie. I always admired Carrie because she is so strong in her beliefs and made sure the children knew our responsibilities on Mother Earth. She wanted us to know how important it is to respect the land in our culture.”

The Shoshone language was spoken daily in Mary’s home, mostly when stories were told as a means of teaching a lesson.

FINDING AND DOCUMENTING HISTORY

“Our stories, our songs, our poetry, and our language are all connected to the land,” she says. “We aren’t above or below what the land provides, we are equal and have to find that balance to live this life.”

Mary Gibson worked in the Elko County Library for 20 years before moving to Maine in 2005 where she studied library science with an emphasis in archives. She came back to visit with Carrie and discovered that her legal papers and those of the Western Shoshone Defense Project—a non-profit organization founded in 1992 to help advocate on behalf of the Dann family—were all boxed and stored in the attic of the Dann’s Crescent Valley ranch.

“Stacks and stacks of materials,” Mary says. “Most of it was packed away in boxes but some of it was stuffed into nooks and crannies. I knew Carrie was very involved in indigenous politics, but until then, I didn’t know to what extent.”

Concerned about so much legal history being stored in those conditions, Mary approached the University of Nevada, Reno’s Mathewson-IGT Knowledge Center Special Collections department to discuss housing the material. Through a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, Mary was able to archive the documents—120 cartons in all—piecing them together like a puzzle. The collection is now open for public view in an exhibit called “Whose Land Is It? The Dann Sisters and the Western Shoshone Defense Project. ”

“I will always feel so honored to have been able to preserve these documents,” Mary says. “There will always be a place for people to come and learn their history, remember their traditional values and our connection to the land. It is Carrie’s wish to use these papers as an educational tool. This collection is vast in historical, political, legal, and economic value.”

Carrie—who still lives on the ranch her father and mother built in 1923—says she donated the papers because they show the actual history of the resistance levied against what was happening to indigenous people, the Shoshone in particular.

Carrie says she feels now the papers will be safe and actually laughed a bit as she recalled her more active days as an “old woman fighting the with the U.S. government.”

“Indian women embrace their power as land defenders at cultural gatherings,” she says. “It is almost always women, absolutely amazing, courageous, strong women, that I hear at activist gatherings.”Mary says it is not unusual for women to be on the front lines in the fight for the rights of indigenous people. Men are present at activist meetings but in her experience having worked with other native indigenous people in this country and worldwide, more women run these grass roots organizations.

TAKING WITHOUT GIVING BACK

Carrie returned from the mountains that autumn day having found very few pine nuts. She says as humans continue to take from the Earth without giving back, we are losing our air, our land, and our water. She says she hopes there is snow this winter, so her people will have water. The drought has all but killed off one field of hay on the Dann ranch and is making traditional medicinal plants and foods, like pine nuts, scarce.

“All Mary and I wanted to know was who gave our land away, our rights away, and our water away,” she muses. “There’s no documentation about that. I never learned what I wanted to know. It’s important for young people to see how it all unfolded. That’s why I gave the papers to the university so the history will be known and documented on what’s happening to the indigenous people as we walk on this earth today.”

SEE IT FOR YOURSELF

“Whose Land Is It? The Dann Sisters and the Western Shoshone Defense Project”

Through March 18, 2016

University of Nevada, Reno Mathewson-IGT Knowledge Center

Special Collections, Third Floor

guides.library.unr.edu/dc/shoshone/, 775-682-5665