A Rugged Sense of Open Space

November – December 2017

Desert National Wildlife Refuge is truly wide open.

BY MICHELLE NAPOLI

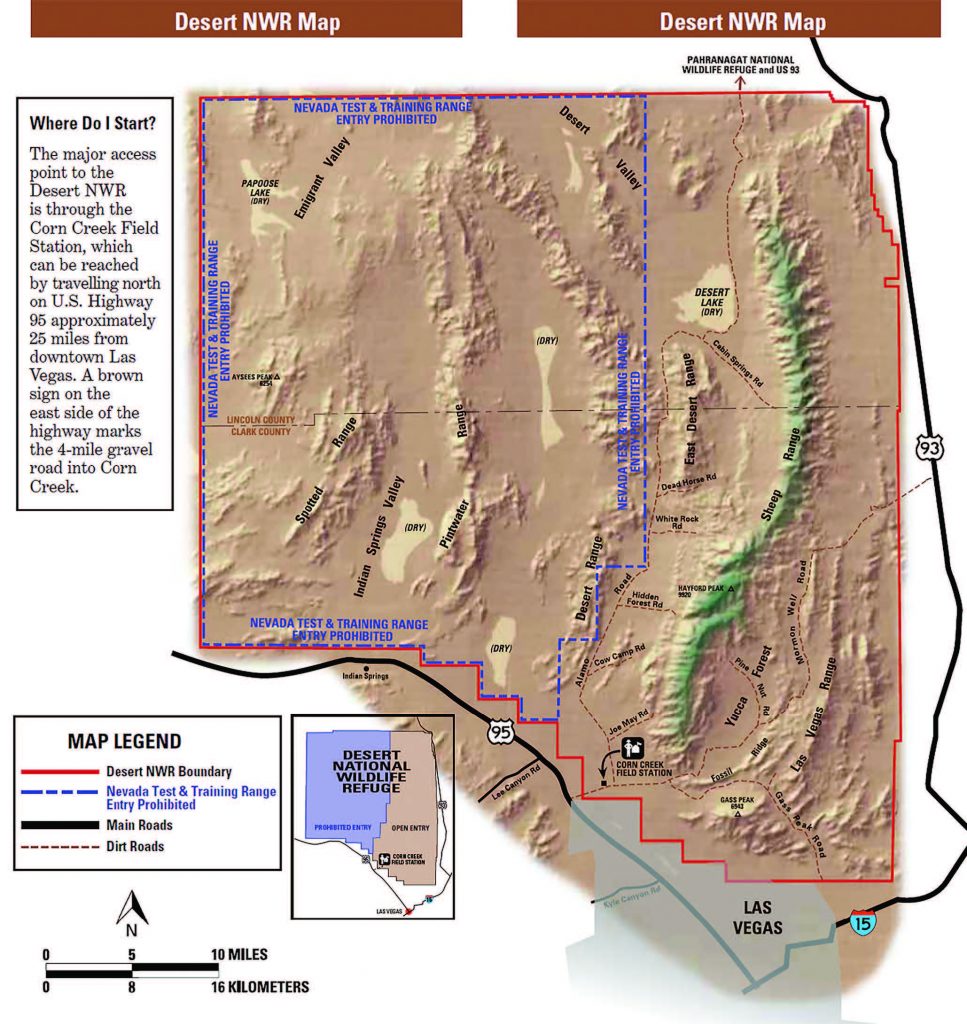

Picture a uniquely diverse landscape spread out across 1.6 million acres. There’s little water, few defined trails, and even fewer roads, but so much to explore. It’s as close as 25 miles from Downtown Las Vegas, yet seemingly far away from the city lights and crowds. If you want to experience what David Choate, a Ph.D. visiting assistant professor at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, describes as “a rugged sense of open space,” the Desert National Wildlife Refuge may be for you.

Originally called the Desert Game Range, President Franklin D. Roosevelt protected the area in 1936 to conserve wildlife resources, particularly Nevada’s iconic desert bighorn sheep. Today, the refuge stands as the country’s second-largest wildlife refuge—the largest in the lower 48.

THE DEFINITION OF TEEMING

With such a large stretch of habitat, bighorn sheep still roam the refuge, though the population has fluctuated over the decades. Currently, about 500 sheep call The Desert National Wildlife Refuge home, according to David, who is also a collaborator with the U.S. Geological Survey. His research has focused on the sheep’s predator, mountain lions, in the refuge.

Bighorn are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg when it comes to the life supported by the Desert Refuge. The refuge hosts seven different life zones—from the saltbrush community in valley floors at elevations below 2,400 feet all the way up to the bristlecone pines found near 10,000 feet in the Sheep Mountain Range—and a dizzying array of plant and animal species.

As a result, the refuge “is representative of a natural system in a region where we are losing a lot of that,” says David.

All told more than 500 plant species, 320 bird species, 50-plus mammals, 35 kinds of reptiles, and four amphibian species (including some considered threatened, sensitive, or endangered) can be found within the refuge. Mule deer, coyote, kit fox, bobcats, rabbits, and bats are among the mammals found there and reptiles include desert tortoise, rattlesnakes, chuckwalla, and collared lizards. Roadrunner, pinyon jay, sparrows, and hummingbirds are just a few of the more commonly seen birds, while raptors include falcons, hawks, golden eagles, and the northern pygmy owl. At various points in between the saltbrush and the bristlecone, the refuge’s flora includes desert wildflowers, Mojave yucca, Mormon tea, Joshua trees, cholla cactus, juniper and pinyon pine, ponderosa pine, and white fir.

Unsurprisingly, birdwatching and wildlife viewing are big draws. The Visitor Center at Corn Creek—with its namesake spring and a pond behind the building—is an excellent spot for early morning birding. In fact, it’s the perfect place to begin refuge exploration, with interpretive displays on the flora, fauna, and history of the area as well as a small system of easy trails, including three that are ADA accessible.

Throughout the refuge, birds are among the easiest wildlife to spot, as well as lizards and other reptiles, particularly in the morning when they are likely to be sunning themselves. Mammals, by contrast, are among the hardest to see. Mountain lions are a mostly nocturnal species and there is only a handful in the refuge. David notes that even a few sheep need a space as large as the refuge to “make a living” in the dry desert environment. Bighorn sheep are active during the day, and will be a challenge to find; your best bet is near springs or other water sources. Always keep a respectful distance from wildlife anywhere, and even more so near water sources, which are critical to their survival.

The more time you spend in the refuge, and the more you get out of your vehicle and explore on foot, the greater your chances of spotting its elusive denizens. David, whose research led him to cover a large portion of the refuge on foot, often camping for months at a time, says don’t forget to look down to find tracks and other signs of animals.

“You’re going to find a lot more, and a lot more stories of what’s come and gone than you would just looking for the animals,” he says.

PROPERLY PROTECTED

The refuge is such valuable habitat because the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service recommended wilderness designations for the majority of the area—more than 1.2 million acres—in the early 1970s; as such, they have been protected and managed as wilderness ever since.

The largest and arguably most stunning of these areas is the 463,000-acre Sheep Range Proposed Wilderness, which takes its name from one of the six mountain ranges in the refuge. Also the largest roadless area remaining in the state, the Sheep Range Proposed Wilderness encompasses all of the different life zones found within the greater refuge, as well as a variety of opportunities for those seeking primitive recreation.

One of two main unimproved roads found here, Alamo Road leads to a number of shorter cherry-stem roads along the western side of the Sheep Range, which in turn lead to some of the more popular hiking areas. Joe May Road, for instance, leads to Joe May Canyon; hikers tend to follow the obvious main wash, and then continue up a side canyon. This is a relatively easy hike and a good location to try to spot bighorn sheep (there is a manmade watering hole here).

Cow Camp, White Rock, and Dead Horse are some of the other spurs from Alamo Road that can be explored. Perhaps the best known is Hidden Forest Road, used to access the trailhead for Hidden Forest Cabin—a popular day hike and overnight backpack destination. A more challenging, approximately 6-mile (one way) hike to the cabin gains more than 2,000 feet in elevation as it makes its way up an old road and enters Deadman Canyon, leading ultimately to a hidden ponderosa pine forest.

The cooler temperatures and shade of the forest make this a nice place to rest, if not spend the night, and there is a picnic table, a fire ring, and basic latrine hidden behind a tree. There is also a spring where water is typically found year round a short distance past the cabin. The cabin’s origins aren’t entirely clear, though it is believed to date back to the early part of the 20th century.

GET OUT AND GET HIGH

For those up for an added challenge and possessing the right route-finding skills, hikers can continue from the cabin to the top of Hayford Peak (the high point of the Sheep Range, at nearly 10,000 feet) or Sheep Peak at 9,750 feet elevation.

Alamo Road runs about 70 miles, from the Corn Creek Visitor Center on the south end of the Desert Refuge all the way to another national wildlife refuge to the north, Pahranagat. If backcountry driving is in your comfort zone, it is a fun way to explore parts of the refuge, but like all unimproved roads, be adequately prepared before you attempt to travel it. At a minimum, much of the refuge outside of the visitor center requires a high-clearance vehicle, and there are areas where four-wheel-drive is recommended if not outright necessary. One prime example, at the northern end of Alamo Road, is Desert Dry Lake. As its name implies, this is a dry desert lake of about 15 square miles. On either end are two beautiful and unique sand dune areas that have formed over time and are worthy of a visit, but the road runs right through the dry lake; at times the extremely soft sand can easily trap a vehicle and conditions may make it impassable.

Two other proposed wilderness areas, the Las Vegas Range and Gass Peak, can be reached by the other main unimproved road, Mormon Well Road, to the east of the Sheep Range. A detour on the Gass Peak Road gives access to Fossil Ridge, a notable area for spotting evidence that the area was once an inland sea; Gass Spring, a relatively easy hike of less than a mile each way; and a more challenging 6.5-mile roundtrip route to the summit of Gass Peak, a great vantage point from which you can see Las Vegas to the south and some of the vast range of the Desert Refuge to the north. On your way to Gass Peak, keep an eye out for rare Blue Diamond Cholla, an endemic species in southern Nevada.

Mormon Well Road will also lead you to some spectacular areas and notable destinations, including Desert Pass Campground—the only formal campground in the refuge, with a half dozen established sites with picnic tables, fire rings, and even vault toilets (but no water)—and Sawmill Road. The latter takes you to the trailhead into Sawmill Canyon, which rises from lower elevation desert scrub up to Sawmill Spring on the western side of the Sheep Range, a roughly 5-mile hike each way.

THOSE WHO CAME BEFORE

Sawmill Canyon is one of a number of gems that should satisfy novice history buffs. While much of the Desert Refuge appears untouched by man, human interaction with these lands can be found in the form of cultural resources left behind by those who came before us.

Look in the right places and you can find “evidence of habitation in various forms for several thousand years,” notes Refuge Archaeologist Spencer Lodge. These include projectile points that indicate hunting took place thousands of years ago, as well as petroglyphs, pictographs, and several hundred agave roasting pits scattered throughout the refuge. According to Spencer, the refuge was a source of important resources for the Southern Paiute, such as sheep, pinyon nuts, agave, and mesquite, as well as an area of spiritual importance for them.

Other historical stops include the old corral and well at Mormon Well Road’s namesake site, which makes for easy exploration. Again, several agave roasting pits indicate American Indian use of this location, while the corral and well are evidence of early 20th century Mormons logging in the area.

And back at Corn Creek, more history can be found. Near the visitor center was once a stop on the short-lived Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad. A short stroll from the visitor center sits a cabin built in the 1920s from railroad ties, following the train line’s abandonment. Corn Creek also served as a ranch for homesteaders at one time. Ranch remains include the orchard area, with pecan, peach, and pomegranate trees.

Though not native to the area, the trees are attractive to the birds.

KNOW BEFORE YOU GO

Camping is allowed throughout the refuge. Car camping must be within 50 feet of roads, and backcountry camping must be at least a quarter-mile away from springs and water developments. Make use of existing road pullouts and campsites that are already disturbed to minimize your impact on the fragile environment. Practice Leave No Trace!

► Remember that you are in a remote area; you are not likely to have cellphone reception, and might not see other people/vehicles for a day or more. Be appropriately prepared with plenty of water, extra food, a good spare tire, and more.

Check with the visitor center for current road conditions; some areas may be impassable at times.

► During World War II, the western portion of the refuge began serving a dual purpose for the military, what today is the Air Force’s Nellis Test and Training Range. Co-managed by the Air Force and Fish & Wildlife Service, that portion of the refuge is off limits to the public.

► Keep a respectful distance from wildlife. Likewise, if you come across any historical or cultural sites or objects, enjoy contemplating their origins, but do not remove or disturb them; it’s the law, and the right thing to do.

► Drone flying is illegal in this– and all–wildlife refuges.