Yesterday: Exotics

November – December 2017

The Nevada Fish and Game Commission Introduces Game Birds From India

By DAVE MATHIS

This story originally appeared in the January/February 1962 issue of Nevada Highways and Parks.

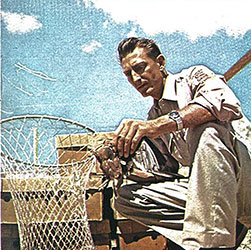

When he came to work as an upland game biologist for the Nevada Fish and Game Commission in 1952, Glen Christensen had no idea that he would one day be living half a world away in a remote section of India. But this is exactly where he found himself in 1959 after he was selected for an unusual and challenging assignment-to go to India on a quest for exotic game birds which might adapt to the desert country in southern Nevada.

“Exotics,” as they are called by game management experts, are species of birds not native to the United States nor, in most cases, to North America. One of the best-known exotics in this country is the pheasant, a sporting bird brought from China and released here during the early 1900s. Another exotic which today thrives in Nevada and other western states is the chukar partridge whose original homeland is in northern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Both the pheasant and the chukar, which was introduced into Nevada in 1935, offer convincing evidence that carefully selected foreign birds adapt well to this area.

Spurred on by its success with these birds, the Nevada Fish and Game Commission continued its search for other types of exotics to fill game voids in the state. Particularly the Commission was eager to find birds suitable for southern Nevada where over a third of the state’s hunters reside, yet which is the only portion of the state where upland game is in short supply. The chukar, which so prolifically adapted to most counties in Nevada, failed to find the southern part of the state to its liking. What was needed here was a game bird which would adapt to the hot, arid environment in Clark and parts of Lincoln and Nye Counties. Culmination of the Commission’s efforts was the project started in 1958 which took the Christensens to India.

The fruits of Glen’s labors are impressive. He trapped and sent to Nevada over 5,000 exotic game birds of four species-the grey Francolin, the black Francolin, the common Indian sandgrouse, and the Imperial sandgrouse. The Francolins are relatives of our chukar and quail and fall between the two in size. The sandgrouse are members of the dove family. The common grouse is a bit larger than our mourning dove, while the Imperial is considerably bigger. The birds were flown from India to Nevada, taken to the Commission’s Mason Valley wildlife management area to recuperate, and then were released, for the most part, in southern Nevada. Only a small number of greys and blacks were turned loose further north in the Mason Valley vicinity.That year the Nevada Fish and Game Commission, in cooperation with the U. S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and the Wildlife Management Institute, decided to experiment by bringing in Indian birds. Earlier the Commission had unsuccessfully attempted to secure exotics from commercial game farm operators in the U. S., from overseas exporters, and from the U. S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. None of these sources was able to provide the right species in the quantities needed for a successful release attempt. By sending its own expert abroad, Commission officials thought that the right bird could be “hand-picked” from terrain similar to Nevada’s. Glen Christensen was the man for the job. A Reno resident and graduate of the University of Nevada, he had written a biological bulletin on chukar in Nevada and was a recognized authority on the subject. With his wife and two children, he departed for India in January, 1959. Jodhpur was selected as headquarters for the project since it was situated on the extremities of the great Indian or Thar Desert country, some 400 miles southwest of New Delhi, which is similar in many respects to the southern Nevada area. Glen’s task was to trap native game birds in this arid region and prepare them for shipment back to Nevada. As far as is known, this is the only project of this type ever sponsored by any state fish and game organization in the country.

The greys and blacks taken to southern Nevada have already brought off broods, indicating that they may adapt to their new home. The sand grouse have not yet indicated that they will take to Nevada but there is still a good chance that they will. The experiment with these birds in Nevada could have significant effects. If they can live here, the birds can also adjust to other western states and thus open bright new hunting vistas in the entire region.

In addition to trapping 5,000 birds with the help of native Indian trappers, Glen spent considerable time investigating the birds’ native environment and the similarities of these conditions to those found in Nevada. About his observations, Glen reported, “Ecologically the country has much in common with Nevada’s southern deserts. Except for the monsoons, annual precipitation is almost identical, temperatures are similar, and plant food types very closely related.”

Aside from making observations of the bird habitat as part of his job, Glen and his family had considerable time in which to observe the people and living conditions of that country. About the people, Christensen had this to say, “Only a very small percentage were formally educated and these all spoke fluent English, as did many of the merchants; all were polite, gregarious, friendly, easy-going and evinced a respect for their fellow men. They lived well together and their children were well-behaved.” Glen and family found Jodhpur short on many of the things they had become accustomed to as necessities of living. But, they adopted a “when in Rome do as the Romans do” philosophy. They bought supplies of staple foods that would last two or more months from the Embassy commissary in New Delhi. For meats and vegetables they shopped in Jodhpur. At first, the only meat available seemed to be big goat and little goat. Eventually, Glen found where he could buy sheep which he butchered himself and he also provided meat through hunting. Mostly, he hunted a large antelope called the Nil Guy or Blue Bull. When it came to hunting, Glen said it was more necessary to understand the people than the habitats of the game. Some of the many religious sects of the country condone hunting and killing but some believe that to kill anything is a serious wrongdoing.

Aside from making observations of the bird habitat as part of his job, Glen and his family had considerable time in which to observe the people and living conditions of that country. About the people, Christensen had this to say, “Only a very small percentage were formally educated and these all spoke fluent English, as did many of the merchants; all were polite, gregarious, friendly, easy-going and evinced a respect for their fellow men. They lived well together and their children were well-behaved.” Glen and family found Jodhpur short on many of the things they had become accustomed to as necessities of living. But, they adopted a “when in Rome do as the Romans do” philosophy. They bought supplies of staple foods that would last two or more months from the Embassy commissary in New Delhi. For meats and vegetables they shopped in Jodhpur. At first, the only meat available seemed to be big goat and little goat. Eventually, Glen found where he could buy sheep which he butchered himself and he also provided meat through hunting. Mostly, he hunted a large antelope called the Nil Guy or Blue Bull. When it came to hunting, Glen said it was more necessary to understand the people than the habitats of the game. Some of the many religious sects of the country condone hunting and killing but some believe that to kill anything is a serious wrongdoing.

Overall, Glen was impressed with India. His personal file of experience was greatly enriched by the trip, and chances are that the “exotics” he trapped may enrich the hunting experiences of sportsmen for years to come, not only in Nevada but in other western states as well.