Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 5

September – October 2016

ODYSSEY OF A GHOST TOWN EXPLORER

FIFTH OF SIX-PART SERIES EXAMINES ABANDONED SETTLEMENTS IN NORTHEASTERN NEVADA.

PART 5: THE JARBIDGE RUNS THROUGH IT

BY ERIC CACHINERO

“Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

“Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

I am haunted by waters.” — Norman Maclean, “A River Runs Through It and Other Stories”

Though Norman Maclean’s depiction of the Blackfoot River in western Montana is exclusive to those waters, I like to think that some of those words exist also under the rocks of Jarbidge River. The words there tell of cool, alpine waters that give life to native trout and Rocky Mountain elk; they tell of its journey over polished basalt and through occasional deep pools; they tell of ancient times. The waters originate at Jarbidge Lake’s heavenly 9,357-foot location, before cascading more than 50 miles though some of the most pristine and pure country in the state: Jarbidge Canyon.

Concepts of both heaven and hell have fused with the Jarbidge River’s treacherous journey and the land it carved through the canyon. Travelers lucky enough to lay their eyes upon the river might swear that it trickles down from heaven itself, but the story wasn’t always so.

Shoshone lore told of a much different past—the canyon inhabited by a cannibalistic devil that would devour souls unlucky enough to tempt the chasm.

As alluring as the Jarbidge area may be, this story is about ghost towns, not rivers and canyons. And although the town of Jarbidge is certainly not a ghost town, it absolutely deserves its role among Nevada’s historical sites. And as heaven, hell, and water seem to be a good place to start in this story, I’ll take you first to a haven for proselytism that eventually succumbed to plagues of biblical proportions, before it died thirsty and suffocated violently into the history books.

THE THIRSTY METROPOLIS

Quality trumps quantity when it comes to northeastern Neva- da’s sparse assemblage of ghost towns. In other parts of the state, you can practically throw a gold nugget in any direction and have it land in a ghost town; such is not the case in this wild corner. Although Editor Megg Mueller and I are running low on gold nuggets to throw, we set out in search of the famed Metropolis, which turns out to be one of the nuggets dating and truly unique ghost towns we encounter during our travels.

Quality trumps quantity when it comes to northeastern Neva- da’s sparse assemblage of ghost towns. In other parts of the state, you can practically throw a gold nugget in any direction and have it land in a ghost town; such is not the case in this wild corner. Although Editor Megg Mueller and I are running low on gold nuggets to throw, we set out in search of the famed Metropolis, which turns out to be one of the nuggets dating and truly unique ghost towns we encounter during our travels.

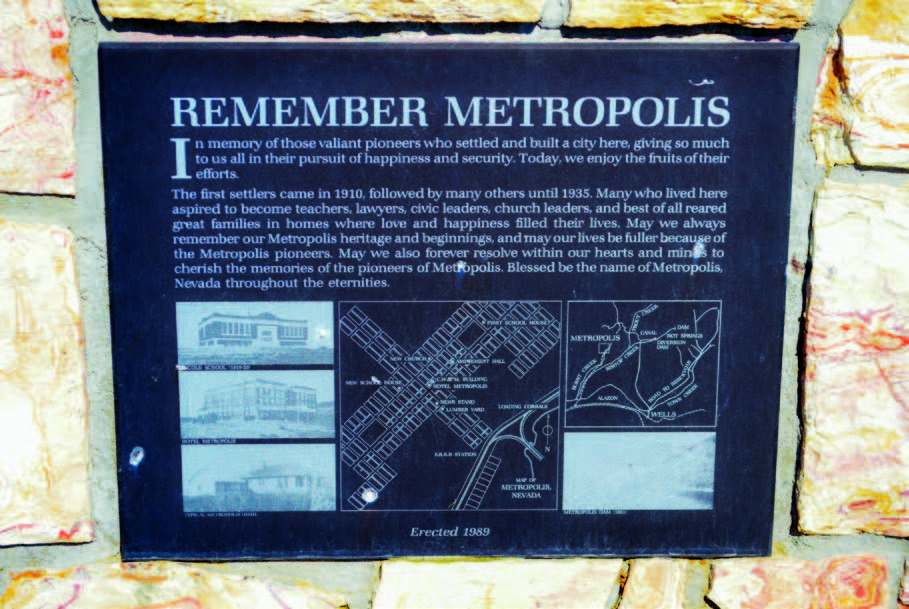

Metropolis’ roots aren’t made of gold and silver like the vast majority of other ghost towns in Nevada, they’re made of agriculture, religion, and promises of a better life. In 1910, New York based Pacific Reclamation Company founded the town, enticing a mostly Mormon community with 40,000 acres of cheap lots and farmland. The town initially lived up to its name. Streets, parks, sidewalks, hydrants, a modern hotel, and other new-age necessities sprang up, and by 1912, more than 700 hopeful settlers called Metropolis home. A 100-foot-tall dam located seven miles east of Metropolis supplemented canals and a water distribution system, and though water was vital to the town’s survival, the system had problems. These were the problems that set the town’s misfortune in motion.

As Metropolis was busy dealing with water issues, so were farmers in Lovelock, located more than 200 miles away. Claiming that Metropolis was using too much of the water that would have flowed to them, Lovelock initiated a court decision that would allow Metropolis enough water to irrigate just 4,000 of its 40,000 acres of crops. Despite the crippling news, Metropolis continued to build, opening a redbrick school in 1914 at the cost of $25,000, though it soon became apparent that the town was dying and the painful exodus began.

As Metropolis was busy dealing with water issues, so were farmers in Lovelock, located more than 200 miles away. Claiming that Metropolis was using too much of the water that would have flowed to them, Lovelock initiated a court decision that would allow Metropolis enough water to irrigate just 4,000 of its 40,000 acres of crops. Despite the crippling news, Metropolis continued to build, opening a redbrick school in 1914 at the cost of $25,000, though it soon became apparent that the town was dying and the painful exodus began.

To add insult to dehydration, in the 1930s, Metropolis was devastated by misfortune of biblical proportions. First, swaths of jackrabbits consumed what little hope was left for the town by ravaging the crops. Then came the typhoid, resulting from subpar sanitation. Next came the invasion of swarming Mormon crickets. A fire in 1936 proved to be the deathblow for Metropolis, though it would be another decade before it was completely abandoned.

Metropolis is famous for its brilliant arch. The facade is all that’s left of the Lincoln School, except its rapidly decaying underbelly, which bears the scars of vandals and deterioration. In addition to the school, remains of the grand hotel join several educational plaques at the site.

Megg and I poke around Metropolis and nearby Angel Lake before making our way to Elko for the night.

INTO THE GREAT WIDE OPEN

The next day, Megg and I find ourselves with a full tank and full bellies, turning off of State Route 225 on to Bruneau River Road en route to Jarbidge. Though I’m familiar with the area we’re traveling to, it is, nonetheless, very remote.

The next day, Megg and I find ourselves with a full tank and full bellies, turning off of State Route 225 on to Bruneau River Road en route to Jarbidge. Though I’m familiar with the area we’re traveling to, it is, nonetheless, very remote.

If you’ve been following this series over the past year, you would know of the terrible weather and vehicle trouble we’ve been facing. It’s my pleasure to announce that the weather shaped up nicely for us on this trip. The vehicle on the other hand…

Alas, not five miles from the pavement, a sound so awful it could only be likened to an ear-splitting wail of a screeching banshee announces itself from our rear left tire. Fearing our trip has come to a terribly premature end, we spend some time assessing the problem, only to find that our ice chest in the truck bed had tipped over and was leaking a bit of water on our brake lines. The problem is hastily corrected and we press on. Turns out some trucks don’t like water too much.

We pass through miles of open desert before approaching the ghost town of Charleston. The town had a reputation for lawlessness when gold was discovered there during the late 1870s. Though the area was mined on and off through the decades, nothing of too much substance was found. A couple small buildings remain and can be seen from the road, but everything is located on private property. Megg and I press on though the scenic Copper Basin before making the steep descent into Jarbidge.

MAN EATER

Jarbidge is special, not spectral. Though the historic site’s population is far fewer than in its heyday, it’s still not considered a ghost town. With that said, Jarbidge certainly has many aspects that lend to a ghost town feel, including historic buildings and an old jail. The town lays legitimate claim to the most remote in the lower 48, and was even the site of the last horse-drawn stage robbery in the U.S. in 1916. Megg and I check in at the Outdoor Inn and begin exploring the town, but not before supplementing our moods with some homemade ice cream served at the inn.

Jarbidge is such a legend, it owes its name to one. It was the Shoshone Indians that first feared the canyon, believing that a cannibalistic giant named Tsawhawbitts (pronounced “tuh- saw-haw-bits”) fed on anyone who entered the canyon. When prospectors began working the area, however, the glitter of gold was brighter than the fear of becoming a rack of ribs at the hands of a cannibal. Folklore tells of several substantial finds—including ore that assayed at $1,200 per ton by sheepherder George Ishman in 1883—though all accounts were lost or forgotten before they created a boom. That was until 1909, when prospector David Bourne spilled the beans, claiming that millions of dollars in gold was ripe for the picking.

The population quickly reached nearly 1,500, though an official name lagged behind. The settlement should have been called Tsawhawbitts, though settlers incorrectly called it Jahabich (pronounced “jah-hah-bich”). The muddled name continued to evolve until a sign, which read “Jarbidge,” was hung in the town. Mining activity remained relatively steady before all major operations ceased in 1941, though several modern operations have resurfaced in recent years.

Jarbidge is a fisherman, hunter, historian, photographer, wildlife enthusiast, and hiker’s paradise. I tour the town with a mountain bike attached to my legs, and a fly rod attached to my backpack. Campsites and redband trout are plentiful, and supper at the Outdoor Inn is the most delicious within 100 miles in every direction bar none.

FINAL DESCENT

Megg and I tend not to do anything the easy (boring) way, so we decide to complete the Bruneau River Loop—the long way out. After a couple wrong turns and subsequent perilous dirt roads, we make a stop at Rowland—the last ghost town of our trip.

Megg and I tend not to do anything the easy (boring) way, so we decide to complete the Bruneau River Loop—the long way out. After a couple wrong turns and subsequent perilous dirt roads, we make a stop at Rowland—the last ghost town of our trip.

Placer mining and farming brought settlers to Rowland, and the nearby Bruneau River gave them life. A post office and sawmill were constructed, and by 1910, nearly 30 people settled in the area. A cyanide mill and cabins were among the additions to the town, and remain as the only ruins of a town that dwindled by 1942.

I wade through seas of cheatgrass to get some photos of the ruins before we hightail it home.

AU/H20

Herds of antelope seem to be in a hurry, easily keeping pace with the vehicle as we travel the last of the dirt roads. The long drive home leaves me with a cheek full of sunflower seeds, reflecting on the importance of rivers and their ability to give life and detract it. Many of the ghost towns in the northwestern corner needed gold and water to survive. Some, like Jarbidge,

had both. Others like Metropolis, had neither. Even though some are ghosts, the history of these towns is still being written, but long after we’re gone, the only words to tell of their existence may lie solely on the bottom of the rocks Maclean so eloquently described.

I am haunted by ghost towns.