Bounding the Silver State

September – October 2018

Drawing the lines that created Nevada’s borders took decades, and still might not be done.

BY ROBERT D. TEMPLE

A treaty with Spain, a skirmish with California, gold strikes, frontier astronomers, a stubborn surveyor, and plenty of errors combined to create Nevada’s unmistakable shape.

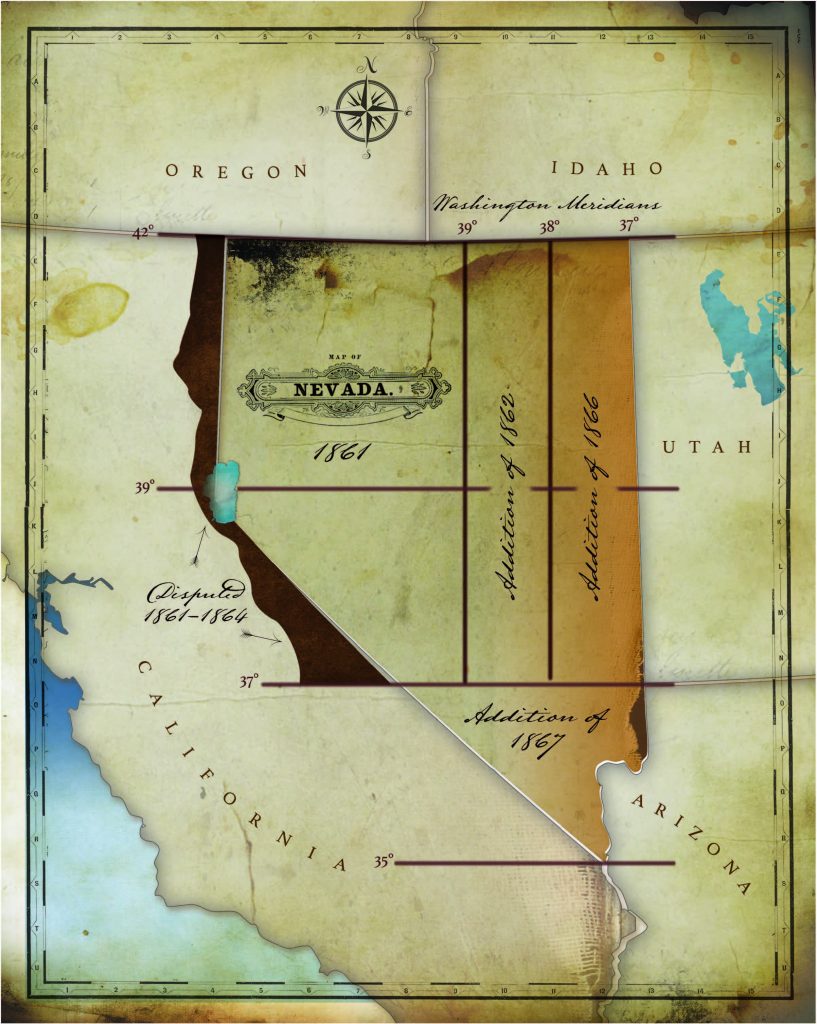

Congress carved Nevada Territory out of Utah Territory in 1861, and President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed statehood in 1864, but it took three more years for the state to expand to its current size. The boundaries were poorly understood then and may still be uncertain. The courts were settling arguments in 1980, and change could still be coming in the east.

THE MISPLACED NORTHERN LINE

The northern edge where Nevada meets Idaho and Oregon is the oldest boundary line in the West. In 1819, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams negotiated a wide-ranging treaty with Luis de Onís, special envoy from King Ferdinand VII of Spain. The Adams-Onís Treaty set boundaries between Spanish and U.S. claims across the continent and the 42nd parallel became a line of division in the West. In the 1850s, it was the unsurveyed boundary between Utah Territory and Oregon Territory.

While it may be easy to decree a line in a treaty, marking it on the ground is not. In 1871, surveyors with the U.S. General Land Office, using astronomical observations, determined the position of Nevada’s northeast corner and marked the point with an 8-foot cedar post. Modern measurements show it was about 600 yards south of the intended position on the 42nd parallel. In 1873, a survey party started at the post and began tracing the line westward, marking it with mounds of earth and wooden posts. After walking and measuring for 310 slightly crooked miles, the party reached another post set in 1869 to mark the northeast corner of California. That placement was better, only about 160 yards too far south—excellent accuracy with the methods available at the time.

As a result of errors along the northern boundary, however, Nevada is about 50,000 acres smaller than Congress intended.

THE DISPUTED WESTERN LINE

Settlers in the foothills and lakes northwest of today’s Reno were uncertain about what political jurisdiction they were in. Most thought they were in Utah Territory, even though Salt Lake City was very far away. They had little connection with California, beyond the high Sierra Nevada Range.

California had defined the northern section of its boundary with Utah Territory as the 120th degree of longitude. To the settlers, the crest of the Sierra seemed a more logical dividing line. The 120th meridian was just a line on a map, established with little consideration of geography.

Beginning in 1856, settlers repeatedly petitioned Congress to form a new territory east of the Sierra. Politics and the great Comstock silver boom led Congress to act in 1861, and they called the new territory “Nevada.”

The enabling act set its western boundary at “the dividing ridge separating the waters of Carson Valley from those that flow into the Pacific,” which is to say the crest of the Sierra, sensibly awarding Nevada the land east of the mountains. However, the act also stated that this area “shall not be included within this Territory until the State of California shall assent to the same.” California did not assent. The parties seem to have neglected even to discuss the matter, and the area remained in dispute and its residents in limbo.

Amid squabbles over elections and tax collection, the dispute reached a crisis in the winter of 1862-1863 with a series of incidents known as the Sagebrush War. In spite of antagonism between the two sides, it seems to have been one of the friendliest border wars in history.

The climactic battle took place on Feb. 15, 1863. A California sheriff brought a posse of 100 armed men to Susanville and laid siege to settlers defending the log residence of their leader, Isaac Roop. The sides exchanged some random shots. After one man received a bullet wound in the leg, the combatants decided to call the whole thing off, had dinner together at a boarding house, and turned the dispute over to their governors.

California kept the land between the Sierra crest and the 120th meridian.

That troublesome boundary line caused continuing controversy. Lines of longitude were much more difficult for surveyors to locate than latitudes because in addition to astronomical observation, the determination depends on time. A one-second time error translates to a quarter-mile error in staking out a meridian.

Between 1855 and 1900, six surveys attempted to locate the 120-degree line, with results differing by more than three miles.

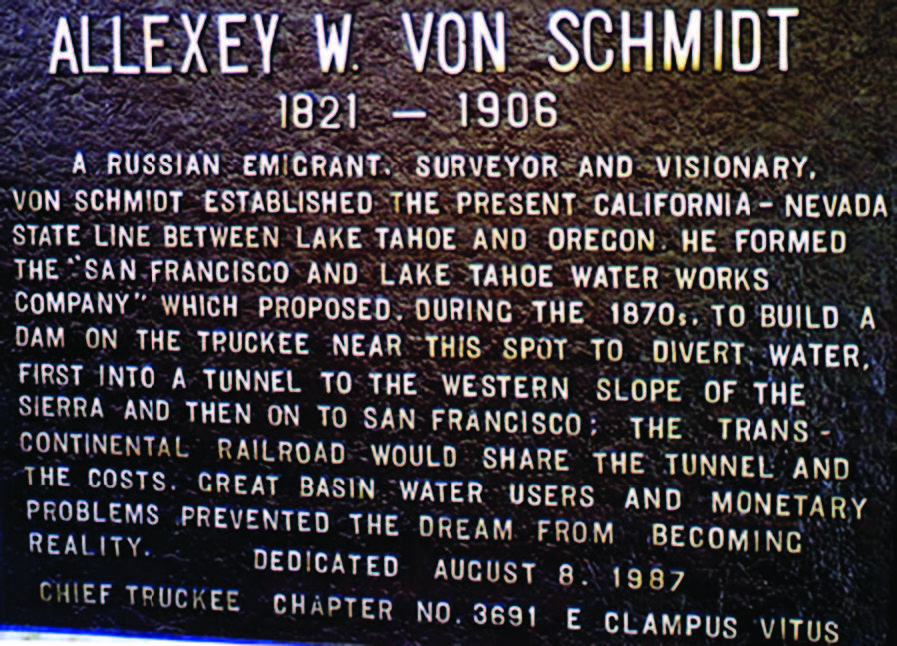

Alexey W. Von Schmidt made a survey in 1872 that ended up being the accepted one. Von Schmidt (whose given name sometimes appears as Alexis), an immigrant from what is now Latvia, was a civil engineer whohad worked extensively mapping public lands and Spanish land grants. He later became a controversial figure in California–Nevada water battles.

Von Schmidt made observations timed with telegraph signals from San Francisco received at the Central Pacific station at Verdi. He quickly became convinced that work completed three years earlier had placed the 120-degree line too far west by some 3.25 miles. Although ordered to base his line on that earlier work, Von Schmidt decided that, since Congress had specified the 120th meridian, he was going to follow the 120th meridian regardless of instructions. His resulting line wanders considerably, as was characteristic of survey work at the time, but modern measurements show he was right about the longitude, within about 450 feet.

But things remained unsettled. Neither state officially accepted the line, and questions about land titles persisted. In 1977, California sued Nevada in federal court to bring an end to the confusion. The states vigorously argued the validity of various surveys carried out more than a century earlier. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that Von Schmidt’s line was the official boundary.

If Von Schmidt had followed orders, Nevada would today be larger by half a million acres.

THE DIAGONAL LINE

Nevada’s slanted line with California is one of the most surveyed boundaries in the country. California’s constitution describes it as a straight line from the intersection of longitude 120 degrees with latitude 39 degrees down to the Colorado River at latitude 35 degrees. The calculations for an oblique line are complex, with continuous change in latitude and longitude as well as correction for the curvature of the earth. It took five painstaking tries to get it right.

Nevada’s slanted line with California is one of the most surveyed boundaries in the country. California’s constitution describes it as a straight line from the intersection of longitude 120 degrees with latitude 39 degrees down to the Colorado River at latitude 35 degrees. The calculations for an oblique line are complex, with continuous change in latitude and longitude as well as correction for the curvature of the earth. It took five painstaking tries to get it right.

At the north end of the slanted line, a California surveyor, trying to locate the angle point in the boundary, discovered in 1855 he was unable to mark it because it lay within Lake Tahoe (then called Lake Bigler). This surveyor, George H. Goddard, apparently did a careful job, establishing sight points on the shores to define lines within the lake. However, California never paid him for the work, so he never turned over his detailed records.

At the south end of the line, Lt. Joseph C. Ives, U.S. Army Topographic Corps, determined in 1858 the point where the 35th latitude intersected the Colorado River. He also re-established the end point on the shore of Lake Tahoe and marked sections of the line. But in 1861, Ives quit his job and joined the Confederate army. With that, his work fell into obscurity, and later the marker he placed on the riverbank washed away.

In 1863, the two governments appointed a new boundary commission, with J. F. Houghton representing California and Butler Ives for Nevada Territory. They assigned fieldwork to John F. Kidder, a prominent civil engineer who later became a wealthy owner of railroads and mines. Indians and a blizzard interrupted Kidder’s work, his funding ran out, and the survey remained unfinished for a decade.

In 1872, Nevada and California hired Alexey Von Schmidt to survey and mark their entire shared boundary. Following his work on the northern segment, Von Schmidt moved to reproduce the incomplete Houghton-Ives line. After running a trial line south, he found that a change in course of the Colorado River required that he shift his line about a mile and a half to the east. He worked back northward, making corrections, but ran out of money and left the job unfinished. This left a kink in the line near today’s Pahrump.

By 1889, improved methods had allowed the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS) to lay out a national grid. This led a new team of surveyors to discover Von Schmidt’s errors. Observing that the various surveys differed by nearly a mile at the south shore of Lake Tahoe, USC&GS started over and reran the line in 1893-1899. Both states accepted this straightened-out version.

Topo maps continue to show the historically important Von Schmidt line. Its acceptance along the entire 405-mile oblique boundary would have made Nevada about 100 square miles larger.

THE SOUTHERN TIP

The first southern boundary of Nevada Territory was the 37th parallel, about 60 miles north of present Las Vegas. Nevada achieved its current southern limits on Jan. 18, 1867, when it absorbed the portion of Arizona Territory west of the Colorado River. This is the entire southern tip of the state, including all of Clark County. Congress decided Nevada would be better able to oversee the population boom expected following the discovery of gold in the area. Arizonans protested vigorously, but their alignment with the Confederacy during the Civil War won them little sympathy.

Originally, the Arizona boundary followed the middle of the Colorado River. However, rivers have the inconvenient habit of changing course, a frequent problem along the Colorado’s lower stretches. Confusion caused when bits of land migrated between the states following flood events wasn’t resolved until 1961. A compact between Nevada and Arizona redefined the boundary below Davis Dam as a series of straight-line segments running between 31 monuments placed along the river.

THE MIGRATING EASTERN LINE

When Congress created Nevada Territory, the eastern boundary was the 39th degree of longitude west of Washington. That line, about 2 miles west of the more familiar 116th Greenwich meridian, would today exclude Elko and Ely.

With discovery of gold east of the 39th Washington meridian, the Nevada territorial delegation to Congress requested moving the boundary one step farther east, to the 38th meridian, which Congress granted in 1862. Four years later, a new gold strike prompted another step, and the border shifted east to the 37th meridian, where it remains. These eastward shifts took about 37,000 square miles away from Utah Territory.

Nevada is unique in this large expansion of its borders after admission to the Union. Missouri acquired additional territory in 1836, though less than a tenth the area of the thick slices added to Nevada. The additions of 1862 and 1866, plus the southern tip in 1867, about doubled the size of the state.

The survey of Nevada’s eastern boundary took place in 1870. The starting point was in the middle of the Central Pacific Railroad track near where Nevada Route 233 crosses the line today near the town of Montello. Astronomical observations and triangulation from an observatory in Salt Lake City had established the position of Pilot Peak, close to the boundary line in Elko County. Direct measurement east from Pilot Peak determined the longitude at the railroad, the 37th Washington meridian (114 degrees 2 minutes 48 seconds west of Greenwich). From there, surveyors ran the line north to the approximate 42nd parallel of latitude as determined by sextant observations. Back at the initial point on the railroad, the survey party headed south, reaching the Colorado River at a distance of 356.3 miles.

Modern measurements show the line wavers by plus and minus half a mile or so because of survey errors, averaging about 700 yards too far east. Because of this, Nevada gained some 120 unintended square miles from Utah.

A change may be coming along this boundary, however, if local voters and Congress can ever agree to it. A 15-square-mile piece of Utah could transfer to Nevada some day, uniting the town of Wendover, Utah, with larger and more prosperous West Wendover.

Local voters agreed to the change, and enabling legislation went to Congress in 2002, where it died in the Senate. Wendover’s City Council reconsidered the matter in 2006 and narrowly voted to halt the annexation process.

There are no current measures before voters today, but stay tuned because Nevada just might grow again.