Yesterday: The Day of the Gunfighter

September – October 2019

BY ROBERT LAXALT

This story originally appeared in the Fall 1964 issue of Nevada Magazine.

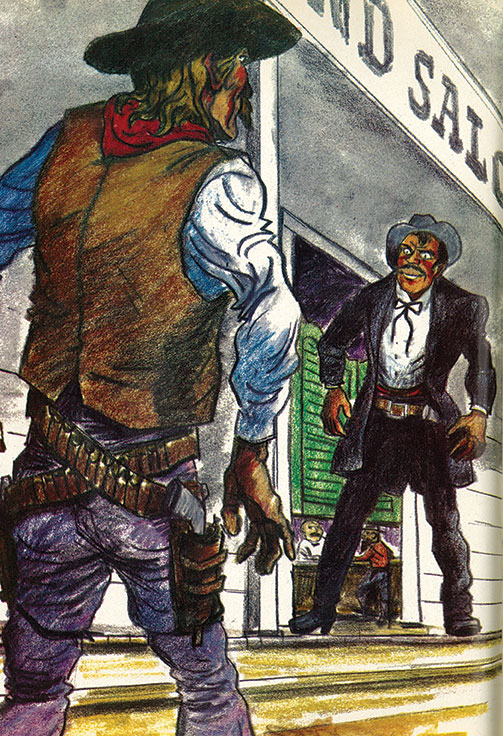

The marshal waited alone in the sunbaked street. In his lean and tapered frame, he had the air of a mail relaxed. But behind the quiet eyes in the clean-shaven face, there was an inward tension like a coiled watch spring. His hands hung ready by the twin gun butts in their hoisters. Across the dusty street, the outlaw pushed through the saloon doors.

The marshal waited alone in the sunbaked street. In his lean and tapered frame, he had the air of a mail relaxed. But behind the quiet eyes in the clean-shaven face, there was an inward tension like a coiled watch spring. His hands hung ready by the twin gun butts in their hoisters. Across the dusty street, the outlaw pushed through the saloon doors.

When he had stepped off the boardwalk, the marshal’s voice cut his advance short like a whiplash. “That’s far enough, mister.”

The outlaw laughed. “All right, marshal,” he said. “Let’s go to it.”

But the marshal said quietly, “It’s your play, mister.”

There was an instant’s pause, and then the outlaw’s hand flashed downward. But the marshal’s six-shooters spoke first, and the outlaw, a look of surprise on his face, tumbled forward into the dusty street.

So goes the popular image of the western gunfighter. If the marshal, sporting drooping moustaches and baggy pants, had been hiding outside the saloon doors clutching a five-shooter recently drawn from his bellyband, had shoved it into the outlaw’s stomach and snarled, “Draw, you coward” and after hauling his man to the justice of the peace and pocketing half the fine, had returned the the interrupted faro game he was running on the side, the image would have been no further from the truth. In fact, much closer.

What has been done with that uniquely American legend of the gunfighter is a remarkable thing to behold. Each age has stamped its desires upon him, from the incredible single handed exploits of Ned Buntline’s writing day to the cowboy troubadour of immaculate costume and a heart ever faithful to his horse; the realistic postwar outcast of rude garb, haunted and hunted and trying to live down his wild past; and the natural progression into the most ridiculous extreme of all—the gunfighter who, while blowing the smoke from the barrel of his gun, reflects in thinly disguised psychological terms on the childhood traumas that made him what he was.

Where the gunfighter will go next is anybody’s guess. But with the gamut nearly run, chances are that the next go-round, which in such assorted ways has already started, will unfortunately be one of satires and exposes.

The hole-pokers will find plenty of ammunition, some of it deserved, in such assorted truths as the fact that Billy the Kid was an ugly little killer who never gave a man anything amounting to an even break; that because of the size of his nose, Wild Bill Hickok was known in some quarters as Duck Bill; that Wyatt Earp was a gambler first and a lawman incidentally and part-time; that the classic quick draw showdown usually amounted to having your gun out and ready when you challenged a man; and that even the word cowboy was originally a term of derision, literally translated as the boy, not yet a man, who tended the cows.

If there is anything left of the legend after this has been accomplished, it will be a minor miracle. Yet, the gunfighter is mighty elastic, else he would have died long ago. The end result may well be that we will finally see him for what he was, a believable human with human shortcomings. And if for once we can judge him by the morality of his own time, and not ours, he may still emerge as a formidably heroic hunk of clay.

The old frontier quip that Colonel Colt made all men equal was more accurate than it was blasphemous. Though he personally never lived to see the production of the great gun that bore his name, the Colt’s Peacemaker in effect marked the end of the time when men settled their personal quarrels with knives. His genius, coupled with the boost that the Civil War gave to the perfection of killing instruments, at last gave men of violence hand guns that could shoot fairly straight and stood a chance of going off more often than not.

However, such a fearsome weapon as the Bowie was not to be cast away overnight. Still holding to the respected traditions of knife fighting and a little suspicious of how dependable a pistol really was, there were few gunfighters in later years whose body arsenal did not include a Bowie. But its day for much other than drawing blood to settle an argument not important enough to throw one’s life away on was pretty nearly done.

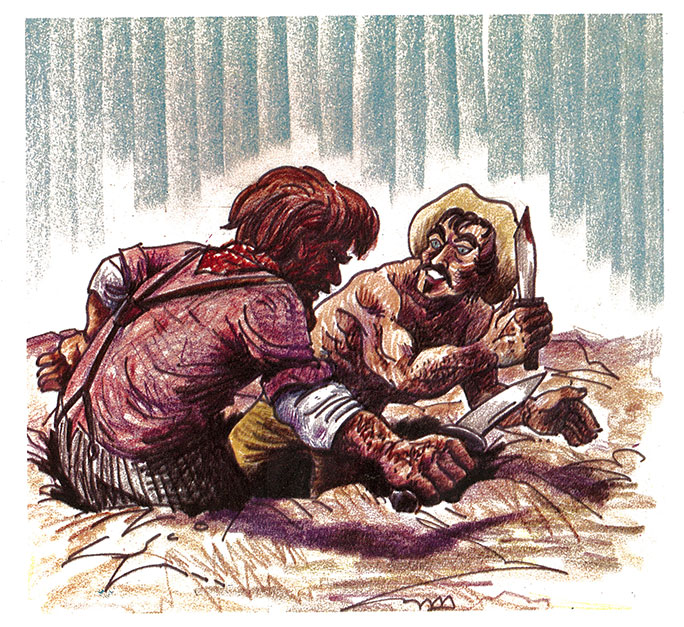

Probably the last of the classic knife duels to the death was fought by Clay Allison of Texas, a novelty in his time in that he wore all the fancy trappings of a modern movie gunfighter. Tall, black haired, black bearded and handsome, he was nevertheless a dangerous man with a gun. And when drunk, he was a demon.

On one of his drinking sprees, he got into an argument with a rancher who was not a bit impressed with the Texan’s reputation. When the argument reached the point where both men agreed that the world could hold only one of them, they decided to fight it out with knives. Allison, with a flair for the macabre, suggested that they dig a grave together and fight it out inside, the winner to bury the loser.

And so they did, working side by side with shovels in the graveyard. Then, stripped to the waist and armed with Bowies, they jumped down into the hole. The rancher was no beginner with a knife, and the curious crowd of onlookers who were hunched down on their knees around the grave saw an exhibition that had nearly as much finesse as a fencing duel. Before Allison had carved up the rancher’s knife arm enough to sink his Bowi· into him, he knew he had been in a fight. He dutifully buried the loser, but he carried the scars of the duel to his own grave.

And further west in Nevada, Virginia City came in for its own share of knife fight lore when Sam Brown—a repulsive specimen happily described by writers as “a reptilian brute” later, when he was safely dead—supposedly carved the heart out of a man in a saloon argument.

And further west in Nevada, Virginia City came in for its own share of knife fight lore when Sam Brown—a repulsive specimen happily described by writers as “a reptilian brute” later, when he was safely dead—supposedly carved the heart out of a man in a saloon argument.

In actual climax, the age in which the gunfighter came into his own was much shorter than is realized. It covered a 20-year span from 1865 to 1885, or roughly, from the end of the Civil War to the time when the West was fairly well organized.

Except in the Southwest, and Nevada, it is significant that no single person either within or without the law earned himself any big reputation as a man killer in such cities as Denver, Colorado, and San Francisco. By this time, communities of any permanence in the West had a good working semblance of law and order, even to the point of ordinances forbidding, the carrying of guns. For the most part, the outlaw elements of thieves and rustlers shied away from these organized towns and made their hideouts in mountain and desert, little out-of-the-way settlements consisting of not much more than a general store and a few saloons, and the mining boom camps such as Virginia City before they grew up. Considering how thinly-peopled the West was, however, there were more than enough badmen around to suit anyone.

ENTER THE GUNMEN

Texas in particular posed a situation unique unto itself. Following the Civil War; it was money poor and torn apart with the· bitterness of carpet bagging Reconstruction. Caught in the struggle for power between negro and White man, law and order was hard put even to know what was demanded of it. This potpourri of politics, poverty, and confused claims of atrocities by both races in a state that prided itself on independent attitudes exploded into violence and outlawery. And out of this were born the West’s first celebrated gunfighters, or gunmen, as was the proper term for those outside the law before the word became a catchall.

Probably the two most famous were William Longley and John Wesley Hardin. Though trying to establish how many men a gunfighter did or didn’t kill will always be a ghoulishly unresolvable western pastime, Longley is said to have done away with 30 men, mostly negroes, before he was hanged at the age of 26. Hardin’s bloody career is reputed to have amounted to killing eight men by the time he reached the tender age of 18, and 39 assorted gunmen, law officers, Mexican vaqueros, negroes, and Indians by the age of 21. Along with Brooklyn-born William Bonney, or Billy the Kid, whose total of 20 men before he was 22 years old is fairly well established, both Longley and Hardin were homicidal maniacs. They were in sharp contrast to the more temperate gunfighters of the Kansas trail towns, such as Wyatt Earp, who killed only five men, and Doc Holliday and Bat Masterson with four each.

Their youthful ages are revealing of one thing. As fiction, movies, and television for some undefinable reason persist in portraying, the West of the gunfighter’s day was not a country filled with grizzled old men. It was dominated by people sufficiently young and strong to have endured the hardships of opening a raw and frightening new land, and the Indian dangers, hunger and thirst, and loneliness that went with it. And in addition to those pioneers seeking new horizons for their growing families, it was an emptying-out place for the youthful adventurers and fortune seekers of many lands, and inevitably, the criminal outcasts of more civilized communities.

To illustrate this, the gunfighters were with rare exception nearly all youngsters. All three·of the Fighting Earps—Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan—were in their twenties during the boom days of the Kansas trail towns. Bat Masterson was in his late teens, and Doc Holliday in his early twenties.

The same thing holds true of the score of southwest gunfighters less well remembered but equally as prominent in their own day. Ben Thompson, a wandering printer turned gambler from Yorkshire, England, was one of the West’s most feared men when he was in his twenties, as was Clay Allison. The Texas bandit, Sam Bass, was only 27 when he was finally run down and killed after many elusive years. Virginia City’s gentlemanly Langford Peel was also in young manhood when he ruled the maneater crowd in that booming silver camp.

Perhaps the best testament that gunfighters and frontiersmen alike were youthful is seen in the example of Wild Bill Hickok. His day was already considered long done when he was shot from behind and killed in Nuttall’s saloon in Deadwood. Although regarded as a relic of the past, he was 41 years old when he died.

The real showdown gunfighter as we popularly know him flourished in the boom towns of a region that belts the middle of the United States. Roughly, it ranged from Deadwood, South Dakota, in the North to Tombstone, Arizona, in the South. Ironically, prosaic sounding Kansas, in such towns as Wichita, Abilene, Dodge, Ellsworth, and Hays City, has a richer heritage of famous gunplay than many of the Western states that make a fetish of their violent frontier history.

Two things caused the boom in this belted area—Texas cattle in the Kansas railroad towns and mining strikes in Deadwood and Tombstone.

Two things caused the boom in this belted area—Texas cattle in the Kansas railroad towns and mining strikes in Deadwood and Tombstone.

NORTH FROM TEXAS

There has never quite been anything in western history to match the dramatic quality of the Texas cattle drives. In its poor postwar days, that sprawling state teemed with upwards of four million cattle. With no local market for them and constant rumors of a beef-hungry East where cattle were selling for ten times more, the Texans swallowed the pride of Civil War hurts and decided to sell their meat to the Yankees.

Up the famed trails such as the Chisholm and the Dodge moved a 15-year cavalcade of longhorns trailherded to those tiny railheads in Kansas that would deign to handle them. This permission was a practical thing, since in many parts of Kansas, the not nearly so meek sodbusters often turned back the herds with armed resistance. Their reason was that the longhorns were carrying Texas tick fever, and the farmers didn’t want their own livestock infected.

The impact of the trail herds was staggering. Forlorn little whistlestops that before had amounted to a few shacks reeled and shook with unexpected prosperity. And then there were the herders or drovers—cowboys as they were later to be dubbed in insult in Dodge City because of their wild antics. Booted and spurred and sombreroed, with a tradition of noisy guntoting and incidentally, still carrying a Civil War chip on their shoulders, they made their invasion of Yankee territory. And if these ingredients were not already volatile enough, there were the added ones of miserable months in the saddle, nerves rubbed raw from stampede and Indian dangers, and the natural yearning for a good bustout at the end of the trail.

The coming of the herds and herders and money went together to give birth to a clique that was to remain remarkably cohesive in the years to come, even to the point of picking up stakes and moving together from one boom town to the next.

It was made up of saloon keepers, gamblers, prostitutes, just plain hangers-on, and professional politicians who could see many advantages in organizing town governments and collecting taxes. This nomadic clique gathered from the four points of the compass and proceeded to set up shop. And the shops were nothing to sneeze at. In the honkytonks, for example, little was spared that money could buy. The mahogany bars boasted of a variety of mixed drinks, and painted prostitutes provided companionship. There were elaborate gambling tables, chandeliers, and even stages for such entertainment as can-can dancing and bawdy ballads.

If the lonely little town had known any such thing as a sheriff or policeman before, he usually turned in his badge or left town overnight. In the face of hundreds of touchy, drunken cowboys carrying guns, and saloon keepers and gamblers with rumored reputations of man killing, it was the sensible thing to do.

Even to the professional organizers, it soon became obvious that the towns could not survive without some degree of law and order. Saloons and regular business houses were making money, of course, but destruction and violence were mounting. Shootings were frequent, costly furniture was being broken in brawls, mirrors and chandeliers and glasses shot up, and the respectable merchant element terrorized by an old Texas custom called treeing a town, in which a whole contingent of cowboys would run their horses down the main street, screaming like Cossacks, shooting in the air and through store fronts, and sometimes, innocent bystanders.

Even to the professional organizers, it soon became obvious that the towns could not survive without some degree of law and order. Saloons and regular business houses were making money, of course, but destruction and violence were mounting. Shootings were frequent, costly furniture was being broken in brawls, mirrors and chandeliers and glasses shot up, and the respectable merchant element terrorized by an old Texas custom called treeing a town, in which a whole contingent of cowboys would run their horses down the main street, screaming like Cossacks, shooting in the air and through store fronts, and sometimes, innocent bystanders.

Men of reputation, who were not Texans, were needed to keep the cowboys in line. Since there were not many around, first thoughts turned to such early frontiersmen-scouts as Bear River Tom Smith and Wild Bill Hickok. The latter was supposed to have killed 43 men, not counting Indians. But of course, the gunfighting fraternity knew better, since they were not averse to telling a few stretchers themselves.

SAGA OF WILD BILL

Though Hickok did more than a creditable job in holding down the cowboy crowds in Abilene, thereby setting the pace for marshals that were to follow, he was pathetically out of his time. Even in appearance, he was an oddity with his flowing, shoulder-length hair, crimson sash, and body arsenal of guns, knives, and clubs, when the professional society was tending toward such conservative dress as tight-fitting sack coats and bowler hats.

The last fortunate thing that happened to him was the way he died. At the lowest ebb of his life, drunk most of the time and reduced to begging handouts to keep him in gambling money, he walked into a poker game in Deadwood. Though he insisted on sitting in his usual place with his back to the wall, the rest of the players joshed him out of it.

A shabby vagrant named Jack McCall was standing at the bar. For some reason known only to himself, he edged around behind Hickok and shot him in the back of the head.

So Wild Bill was cowardly assassinated while he sat for the first time with his back to the door, by a gun that had only one good cartridge in it, and while dying, smiled and faced up what was to become known as the Dead Man’s hand—aces and eights with a queen kicker.

It took a while for these classic elements to be appreciated by the public. In fact, his murderer, McCall, was actually let go in Deadwood because of a fabricated story of revenge and the low esteem in which Hickok was then regarded. The Eastern journals went wild with the story, dredged up Hickok’s past exploits, and generously added a few more men to his credit. When the West realized what a man it had lost, it sentimentally re-arrested Jack McCall and hanged him.

There is a certain hypocrisy in concealing the fact that the gunfighting marshals we idolize now were selected from the wandering clique of gamblers and saloonkeepers. In the first place, gambling was part of that frontier day in nearly every town and settlement. Moreover, these men were just about the only ones around in the boom towns whose occupation demanded that they be handy with a gun. And of course, the gambler’s poker face for bluffing purposes didn’t hurt, either.

However, they were not about to give up full time at their lucrative tables by taking on a lawman’s job at little pay and risking their lives daily to boot. Though a few forgotten men like Bill Tilghman and Ed Masterson did do just that, the great majority were just not that civic minded. So, the town fathers had to make the jobs attractive enough to draw capable men. This they did for the most part by making lawmen tax assessors on the side, with the right to keep a share of the collections, and also, a share of the fines levied against those they arrested. With this arrangement, some lawmen in the boom towns could count on making as much as $20,000 a year, which even to a gambler was quite well worth the risk. The unfortunate byproduct was that the job of law officer was too often thrown into a vicious form of politics, which later was to reach a head in Tombstone, Arizona.

On the other hand, the money lure helped to do the job. It drew out such men as the Earps and Bat Masterson, who were to do heroic work in curbing lawlessness in general and the Texas cowboys in particular. Though their exploits have been exaggerated out of shape or diminished to nothing, the fact remains that it took much courage to face up to the hordes of Texas cowboys and bring a higher degree of law and order to the Kansas boom towns. The long roster of dead lawmen and the remarkably few who lived to have their adventures penned is evidence enough of that.

Texas never forgave the Kansas marshals such as the Earps. Their original title was promptly changed to the Fighting Pimps, and for many years afterward, such tidbits of information as that Wyatt Earp lived with a mistress all the time he was in Tombstone made the rounds of the state.

GUN PROTOCOL

Many of the finer points of gunfighting originated in Texas, but nevertheless, the art was to reach its highest peak in the cattle and mining boom towns. The violent gentry made a fetish of all sorts of guns, places to hide them, how to get them into action; and even how to shoot. There were Colts, Smith and Wessons, Whitneyvilles, and Hopkins and Allens; revolvers and derringers; six-shooters and five-shooters; rubber grips and walnut grips; smoothed down actions and tied back hammers; open holsters, shoulder holsters, swivel holsters, and even leather-lined pockets.

A lot of it such as fanning or shooting two guns at the same time was nonsense of a sort, because when things came down to the serious business of fighting for one’s life, fanciness was forgotten. More often than not, gunfighters adhered to the simplest of trappings, dependable guns in plain, stripped down holsters or even stuck in the same belt that held up their trousers, and of course, the ability to shoot straight in a pinch.

The unswerving code of conduct for showdown duels that we now take for granted was at best a flexible thing. About the only hard and fast rule of ethics was that of not shooting an unarmed man. This also had its practical considerations, in that it kept one inside the all-inclusive excuse of self-defense. Holding a gun in another man’s stomach and challenging him, shooting in the back, or rearing up unexpectedly from behind a rain barrel with shotgun blazing were common occurrences. However, there was widespread disgust when someone carried this too far, such as Billy the Kid.

Probably the closest thing to a fair fight that Billy the Kid ever mixed in was when he killed Badman Joe Grant. Hearing that Grant was gunning for him, Billy the Kid made it a point to hunt him out in a saloon. But he had no intention of calling the self-styled badman to account just then.

Instead, he cajoled Grant with smiles and jokes and drinks. In one of these moments of horseplay, he asked Grant if he could see his gun for a minute. Grant was drunk and thrown off his guard enough to hand it to him. Billy the Kid looked the gun over and secretly turned the cylinder so that the hammer would hit on an empty chamber. Then he handed the gun back to Grant, and a little later, turned deadly serious and called him to carry out his threat. When the badman lay dead, Billy the Kid was not content to let it go at that. He had to tell the saloon crowd just how clever he had been.

Fast draws had their place in situations like barroom brawls or gambling quarrels. When a man did not know his adversary well enough to predict what he was going to do, it paid to be quick in getting a gun into action. The boom town marshals used quick draws to advantage against the Texas cowboys, but almost always buffaloed them with pistol whippings rather than kill them. Wyatt Earp, essentially a humane man, was a past master at this, which accounts for the small number of men he killed in his gunfighting days.

However, this was only one part of the gunfighting picture, and at that, it was no particular disgrace to back out of a fight when you were beaten to the draw. There probably wasn’t a single gunfighter who did not choose this out in preference to death at one time or another in his career. Both Clay Allison and Ben Thompson, tested and proven for blind courage, are said to have backed down to Wyatt Earp, with one of them offering the logical explanation that it wasn’t his day and he didn’t particularly feel like dying just then.

Personal quarrels often amounted to long sieges of insults and threats upon the other man’s life. If these antagonists ever got to the serious stage, they could spend days trying to get close enough to each other with drawn guns to shoot at point blank range. The most common threat of the day was, “I want just ten feet off you,” and sometimes, only four feet of distance.

Western history is filled with inglorious gunfights outside this range. The deadly Doc Holliday was supposed to have fired an entire revolver full at a barkeeper at long saloon range, scoring only a minor crease.

Then there’s the story of two men in a street fight, who chased each other all over town until they had shot up all their ammunition. Finally, one of them sneaked down to the hardware store to buy some more cartridges. He entered, breathing a sigh of relief, and was shot down at customer distance over the counter. His opponent had gotten there first.

FIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL

The gunfight at the O.K. corral is of course the note on which all western stories should end. However, this is not because of all the exaggerated elements of right against wrong, heroic lawmen against outlaws in a grim and bloody drama to the death. In its neglected reality, it is even more worthy of remembering, because from beginning to end it epitomized the immense gray zone and the actual unblack and white way of the gunfighter’s West.

Tombstone, Arizona was the last of the lawless boom towns. Perhaps in some sort of unconscious awareness of this, its inhabitants chose to make it the most lawless of all. Knifings, shootings, and killings were almost daily fare. But by that time, the West was entering into a respectable age and was sick and tired of violence. In effect, the gunfighter had outlived his day and had fallen into disrepute.

The political intrigue that had dogged the boom towns reached a rife level in Tombstone, especially in the grab for local government posts. One facet of this was the attempt of the Earp brother faction to unseat the so-called cowboy group that had placed gambler Johnny Behan in the job of sheriff and assessor, and which included in its ranks a number of known thieves and rustlers. Freewheeling journalists of the frontier variety took highly-biased sides, adding fuel to the fire and unhappily obscuring for all time any objective assessment of the state of affairs.

There were deals and counter-deals and finally one of them set the stage for the O.K. corral showdown on October 26, 1881. Wyatt Earp, then a part-time deputy marshal running a faro game on the side, made a deal with cowboy Ike Clanton whereby the latter would inform on three of his friends who had held up a stage and killed its driver, a popular man in Tombstone. Clanton was to get the reward money, and Earp, by his own later testimony, “the glory,” so that he could win the next sheriff’s election.

However, word of the deal somehow got out. Then followed a succession of, “You told on me,” and, “I did not; you told on me.” From then on, with both men exposed to the public, the tensions between the two factions led to the bloody business at the O.K. corral.

Even at that, the fight nearly didn’t come off. For the days and morning preceding it, there were the usual threats and challenges, with men on both sides taking turns backing down. In one of these brushes, Wyatt Earp held a gun to cowboy Tom McLowry’s stomach and challenged him to draw and fight, but McLowry declined the invitation.

Then, at two o’clock in the afternoon, with the Clantons and McLowrys either getting ready to leave town or waiting for a shootout, the moustachioed and frock-coated Earp brothers and Doc Holliday went down to the vacant lot next to Fly’s building, only later known popularly as the O.K. corral, to arrest them for disturbing the peace.

In the later murder charges, flights from arrest, and the welter of disclaimers that followed the showdown, it will be forever impossible to find out who started the gun play, whether two of the cowboy group were unarmed and defenseless, and from there, whether it was a fair fight or a murderous massacre at point-blank range. But when the thunderclaps had stilled and the billows of white smoke had lifted, three men of the cowboy group lay dead, and two of the Earps were wounded. In less than ten seconds, the bloodiest standup fight in the history of the western boom towns had erupted and ended.

And with it, the day of the gunfighter bowed out with the magnificently classic showdown it had been looking for since the beginning. In a grander sense, it was the story of Wild Bill Hickok all over again.