The Sagebrush School

Spring 2024

Nevada’s first generation of writers and journalists were in a league of their own.

BY CORY MUNSON

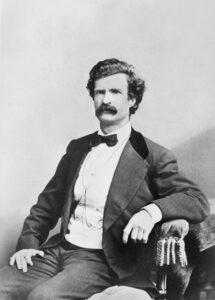

In 1861, Samuel Clemens left his home in Missouri to adventure in the American West. In Carson City, he became obsessed with finding gold and spent 11 months galivanting across the desert. When he ran out of money, Clemens moved to Virginia City to be a newspaper reporter for the “Territorial Enterprise.” Three years later, he left Nevada with bright prospects and a brand-new pen name—Mark Twain.

It’s far from a lucky bit of trivia that Twain got his start in the Silver State. In the late 1800s, Virginia City and surrounding communities were home to a strangely high concentration of talented writers. Early Nevada plays, poems, books, and newspapers were so unique that in 1893, historian Ella Sterling Cummins regarded them as an isolated literary movement, which she named the Sagebrush School.

THE ROTTEN BOROUGH

Nevada’s literary golden age began in 1859, when the largest silver strike in U.S. history was made at The Comstock Lode. Unlike California’s gold-rich rivers that triggered the Gold Rush, The Comstock’s silver was difficult to reach. Constructing and operating the mines was logistically complex, requiring investors, lawyers, surveyors, engineers, and countless skilled laborers.

Within months, the then-sparsely populated territory hosted some of the densest—and most remote—urban cores in the West. When Virginia City was founded, the nearest cities were Salt Lake City—500 miles away—and San Francisco.

Government-sponsored justice was mostly absent throughout the silver rush. Instead, the first cities were run by powerful barons who used their considerable wealth to influence lawmakers and business leaders. Corruption grew to such a shameless level that Nevada was often referred to as the “rotten borough.”

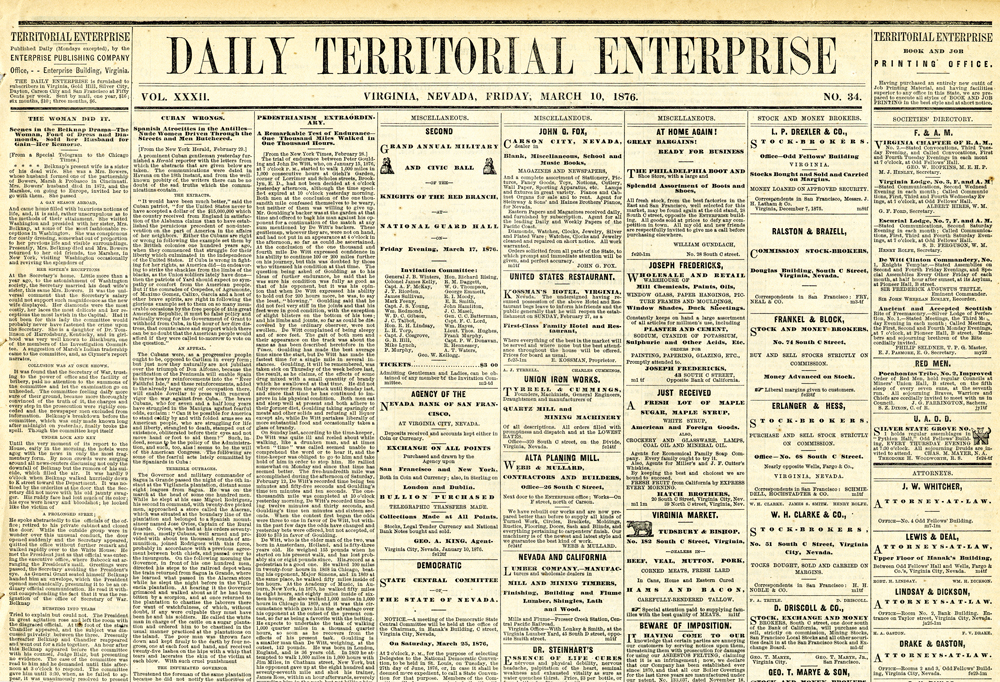

It seemed that the only check on this culture of avarice was through newspapers, and from the earliest days, Nevada’s writers played an outsized role in criticizing this era of excess.

FRONTIER JOURNALISM

Like most people back then, Sagebrush School alumni came to Nevada seeking wealth, fame, and excitement. Residents of the West’s settlements were hungry for news and entertainment.

The writers probably wouldn’t have acknowledged that they belonged to a literary movement or had much in common with one another, but today we can appreciate their shared traits.

Many, like Mark Twain, were writers at heart who happened to moonlight as editors and newspaper reporters for the stable paycheck. In their spare time, they were theater critics, novelists, playwrights, poets, biographers, and historians. They were a scholarly group who couldn’t help but sprinkle flowery prose or Shakespeare and Greco-Roman mythology into their daily reporting. But they were not pedantic: They knew their audience was mostly everyday folk, and writings reflected that with slang, colorful metaphors, and plenty of creative spelling to mirror the local vernacular.

Many, like Mark Twain, were writers at heart who happened to moonlight as editors and newspaper reporters for the stable paycheck. In their spare time, they were theater critics, novelists, playwrights, poets, biographers, and historians. They were a scholarly group who couldn’t help but sprinkle flowery prose or Shakespeare and Greco-Roman mythology into their daily reporting. But they were not pedantic: They knew their audience was mostly everyday folk, and writings reflected that with slang, colorful metaphors, and plenty of creative spelling to mirror the local vernacular.

For the most part the Sagebrush School writers were a young crowd. When Samuel Clemens arrived in Virginia City, he was 26 years old. The editor who hired him, the legendary Joseph Goodman, was 24. They were idealistic and took their role as the public conscience seriously. They publicly harassed perceived villains in their articles and applauded heroes who stood up for their principles. They were skeptical—even critical—of the justice system and were not afraid to call out corruption, like in 1864, when Goodman’s reporting forced all members of the state supreme court to resign.

FAKE NEWS

One hallmark of Sagebrush School writers was their fondness for producing fake articles—also called “quaints.” In an era when public officials and journalists could find their opinions altered for a price, misinformation and downright lies were easily printed. To combat this, Sagebrush School writers published articles that appeared true and authentic, but careful reading revealed the story to be entirely fake.

These hoax stories were written to entertain, but they also aimed to teach readers to pay close attention and read critically. In Dan DeQuille’s article “Solar Armor,” it was reported that an inventor had successfully created an air-conditioned suit designed for crossing the desert. Despite the ridiculous premise, the article is filled with scientific details and seemingly real interviews. Readers might find themselves convinced right up to the last sentence, when it’s revealed that the inventor was discovered frozen solid with an icicle growing out of his nose.

There was no greater success for a hoax article than when it was repeated by gullible readers or, better yet, reprinted as fact in other newspapers. Such was the case in 1863, when Twain reported on a man who massacred his wife and nine children outside Carson City. There are plenty of clues in the article that point to it being another quaint, including how the murder weapon switches from an axe to a club to a knife. There was no massacre, but that didn’t stop San Francisco papers from making the story a headline.

IN GOOD COMPANY

Twain was a brilliant writer, but his style was highly influenced by the other talents in the Sagebrush School. Many of his peers have not earned recognition in the 21st century, but some went on to have illustrious careers of their own.

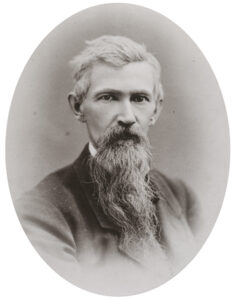

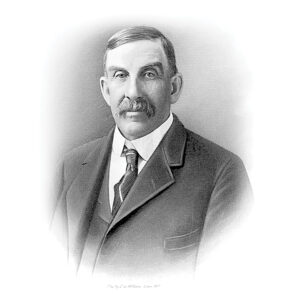

Joe Goodman was one of the most talented writers to work in Nevada. Editor of “The Territorial Enterprise” from 1861-1874, he fostered the career of his friend Twain. He took his work as an editor seriously, and his newspaper was renowned for fact-based reporting and spotlighting wrongdoing on The Comstock. After leaving Nevada, he became fascinated with Mesoamerican cultures and was instrumental in building the cypher that decoded the Mayan writing system.

Dan DeQuille—real name William Wright—was probably the school’s most prolific writer. Beyond writing for “The Territorial Enterprise” and other western newspapers, he was a novelist who wrote the first major work of The Comstock’s history. His talent has often been compared to Twain. According to Joe Goodman, “Dan was talented, industrious, and, for that time and place, brilliant. Of course, I recognized the unusualness of (Twain’s) gifts, but he was eccentric and seemed to lack industry.”

Sam Davis, who arrived in Nevada a generation later, was a fierce critic of corruption and was willing to let his fists defend what he wrote. After Davis criticized U.S. District Attorney Charlie Jones for his handling of a bribery case, the two men had a fist fight on the steps of the Carson City post office. To quote Davis, “You wrote what you dammed well-pleased, but you’d better be prepared to back it up when the offended party came-a-callin’.”