Tuscarora

Spring 2024

Peace and pottery in Nevada’s remote northeast.

In 1962, a Washington D.C.-based potter named Dennis Parks stopped in Tuscarora during a cross country road trip. He had heard about the remote Nevada community—located an hour north of Elko—from a friend who had recommended it as the perfect artist retreat. Upon arrival, he found what looked be a ghost town of crumbling brick chimneys and weathered homesteads.

But the town was not dead. Even then, a half dozen residents enjoyed a peaceful life amid its ruins. And who could blame them? The sweeping valley below shimmered with sagebrush rocking in the wind, and a nearby creek babbled between tall grass and wildflowers. The ruins only enhanced the experience, making the town feel ancient rather than decrepit. The place felt isolated, not just geographically but also in time.

Parks fell in love with all of it and decided that Tuscarora wouldn’t just be where he’d go to escape the city. In this near-ghost town, he would build a school.

100 YEARS EARLIER

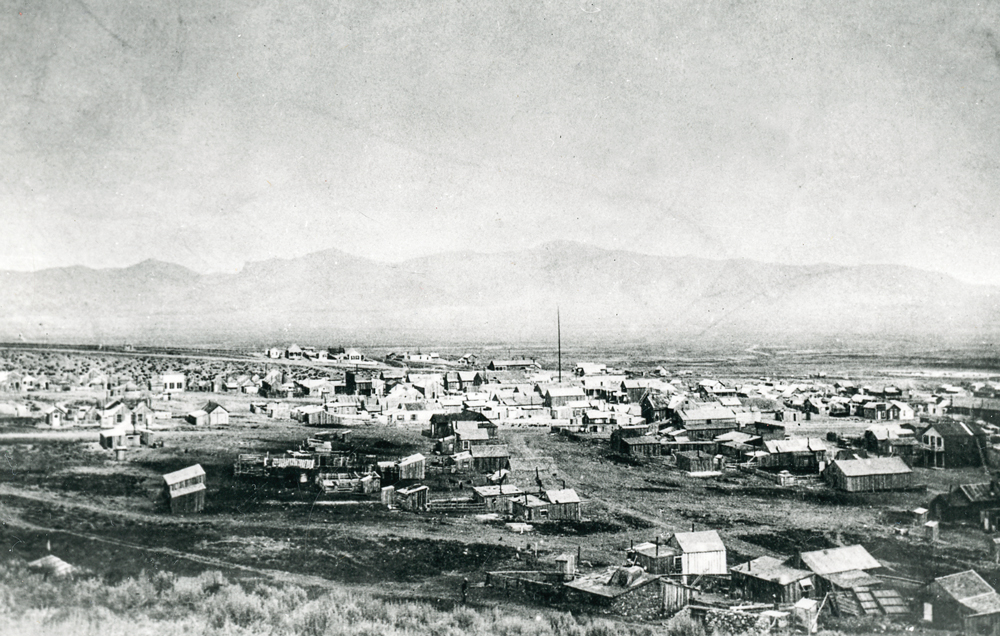

When Parks arrived in Tuscarora, it looked pretty much the same as it had the day the last mine shut down. The town is located partway up the slope of Mt. Blitzen—a less-than-ideal location for growing crops or enjoying mild winters—because that’s where a massive silver strike was made in 1871.

Technically, Tuscarora was founded in 1867 after brothers John and Steven Beard discovered gold a few miles up the valley from the town’s present site. Near their claim, they established a mostly luckless mining community they named Tuscarora in honor of a U.S. gunboat—which in turn was named for an indigenous people from what is now North Carolina.

Tuscarora’s mines soon attracted Chinese workers, themselves unemployed after the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. The Beards gladly hired them all to help run the mills and mines. Within a few years, the town was home to one of the largest Chinese communities in the nation.

After silver was discovered in 1871, the Beards sold all their gold claims to the Chinese, believing the mines spent. The new owners reworked the old mines and extracted millions of dollars in gold over the next few years.

Meanwhile, Tuscarora was booming. By the early 1880s, it was home to more than 3,000 residents, making it the largest town in Elko County. Still, the railroad was 52 miles south in Elko, ensuring that the dusty highway between the two towns stayed perpetually crammed with carts and supplies.

Life in the young town was good and busy. The townsfolk enjoyed luxuries like an opera hall and even a public school with more than 200 students. As a true sign of its success, Tuscarora boasted not one but two soft drink bottlers.

The silver bonanza ended in the mid-1890s, but the town didn’t die; it just slowed down. Even as late as 1920, Tuscarora was home to around 240 people. By then, however, the mines had gone dormant—their equipment sold for scrap metal.

THE TUSCARORA POTTERY SCHOOL

Parks did not immediately move after first visiting Tuscarora in 1962. He and his wife Julie had a life and two sons, and they needed to pay the bills.

Parks earned a master’s degree in ceramics and became an instructor at Pitzer College in California. But his mind continued to return to the quiet village in the Great Basin Desert.

In 1966, Parks decided to test a summer program for his dream pottery school. The 30-year-old teacher arrived in Tuscarora with Julie and some friends, and the group got to work. Cash-strapped and without supplies, they turned to the town and its surrounding landscape for material. A carriage shop became the studio, abandoned mills provided bricks for firing, and mine tailings were harvested for clay. They used their homemade clay—along with sand and sawdust—to build the first kiln, and the first pottery wheel was a cement cast of a rusted steering wheel.

The first program in Summer 1966 was a massive success, attracting seven students for a few weeks. For the next three years, Parks taught at Pitzer then returned to Tuscarora for his summer workshop.

In 1969, the school expanded to a 9-week program that could accommodate 14 students. During the summer, Tuscarora’s population soared to levels not seen in decades. Its residents—now in their 60s and 70s—embraced the new, young crowd. The students immersed themselves in the community, helping with household chores and maintaining the town’s generator. In return, the residents helped fix up the school’s headquarters: a leaning, two-story building that was once a boarding house.

In 1969, the school expanded to a 9-week program that could accommodate 14 students. During the summer, Tuscarora’s population soared to levels not seen in decades. Its residents—now in their 60s and 70s—embraced the new, young crowd. The students immersed themselves in the community, helping with household chores and maintaining the town’s generator. In return, the residents helped fix up the school’s headquarters: a leaning, two-story building that was once a boarding house.

In the remote setting, everybody had to help. Life at the school was as rugged as things got in 20th century America. This was the late 1960s, though, and enthusiasm was high for a return-to-the-earth lifestyle. Students sourced pottery supplies from the desert and maintained the school’s vegetable garden. They even raised chickens, goats, ducks, and rabbits for food.

After the 1969 summer classes ended, Parks decided it was time to relocate.

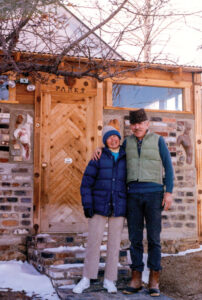

He and Julie withdrew their life savings, bought the boarding house—and two other properties—and moved to Tuscarora permanently.

With the family now giving Tuscarora their undivided attention, the school and its student body continued to grow. In 1972, a new studio was built: a geodesic dome that is still the most eye-catching structure in town.

Parks’ career flourished, and he became a leader in the field of ceramics. Due to the natural restrictions in Tuscarora and the need to ration resources, Parks pioneered creative alternatives to firing pottery. Most clay is fired twice, but Parks perfected a way to do it in a single fire. For his oil-powered kiln, he developed a method that recycled the oil from discarded crankcases. He went on to literally write the book on both techniques, “A Potter’s Guide to Raw Glazing and Oil Firing,” which sold more than 10,000 copies.

CONTINUING THE TRADITION

As the years went on, students became instructors, and a new generation of potters studied under Parks. During the off-season, the school became a retreat for professional artists and teachers.

As the years went on, students became instructors, and a new generation of potters studied under Parks. During the off-season, the school became a retreat for professional artists and teachers.

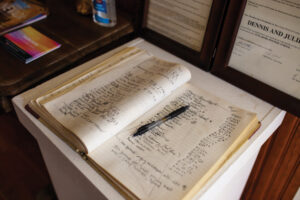

All the school’s visitors can be found in the guestbook, a massive 19th century ledger that never leaves its location near the front door. It is easy to lose track of time flipping through its hundreds of pages and thousands of signatures and comments.

Parks passed in 2021, and while the school continues on, everybody can agree that things are different.

“We call it a beautiful burden,” says artist Elaine Parks, Dennis’ former daughter-in-law.

She, like all the other instructors, does not live in Tuscarora but instead makes the long commute when school is in session. Indeed, everybody who participates in the school takes time out of their careers and lives to keep Parks’ dream alive.

She, like all the other instructors, does not live in Tuscarora but instead makes the long commute when school is in session. Indeed, everybody who participates in the school takes time out of their careers and lives to keep Parks’ dream alive.

Despite the loss of the school’s figurehead, classes continue. Students make the pilgrimage, including an entire high school art class from Idaho that camps out for a week. The school still has dedicated instructors and high-quality sessions. This past summer, the Tuscarora Pottery School offered a raku course and held a two-week certifier class for high-temperature firing.

Despite the loss of the school’s figurehead, classes continue. Students make the pilgrimage, including an entire high school art class from Idaho that camps out for a week. The school still has dedicated instructors and high-quality sessions. This past summer, the Tuscarora Pottery School offered a raku course and held a two-week certifier class for high-temperature firing.

“The students make pots for six or seven days and then do the glazing and then load the kiln and fire it off. That’s always a big fun night,” says Elaine.

But everything that happens at the school today, from repairs to running the nonprofit, is done through a lot of volunteer work and many long hours on the road. If the school is to continue, a new generation will need to inherit the responsibility. Maybe some of them will call Tuscarora their new home: with only one year-round resident, the town is smaller than it has ever been.

“At this point, we’re hoping to get somebody who could live here at least six months out of the year. Someone who is a ceramist and knows how to work on the equipment and tools. Someone who’s kind of handy and can maintain the old boarding house,” says Elaine.

VISIT TODAY

VISIT TODAY

For now, there are plans for classes in summer 2024. And while Tuscarora grows quieter each year, it is still full of life in the summer. Visitors who make the drive during warm months can expect picturesque ruins overgrown with greenery and countless artifacts to inspect.

Stop in town to take a walk along its decaying street grid and then wander down to the cemetery. Or hike up the hill to the big chimney to enjoy the breathtaking view. While you’re at it, mail a letter. The only business in town is a functioning post office—staffed daily—that services the ranches spread out across the valley.

Stop in town to take a walk along its decaying street grid and then wander down to the cemetery. Or hike up the hill to the big chimney to enjoy the breathtaking view. While you’re at it, mail a letter. The only business in town is a functioning post office—staffed daily—that services the ranches spread out across the valley.

And, of course, stop by the school. Someone might be available to show off the historic boarding house or the studio. There is also a gallery/gift shop that offers a beautiful pottery collection created by instructors and friends of the school. You can find branded apparel, books, and your very own honey bear sticker (ask them about that) as well. You might also get a tour of the 1878 tavern-turned-community center, which is packed with exhibits and relics that tell the town’s story.