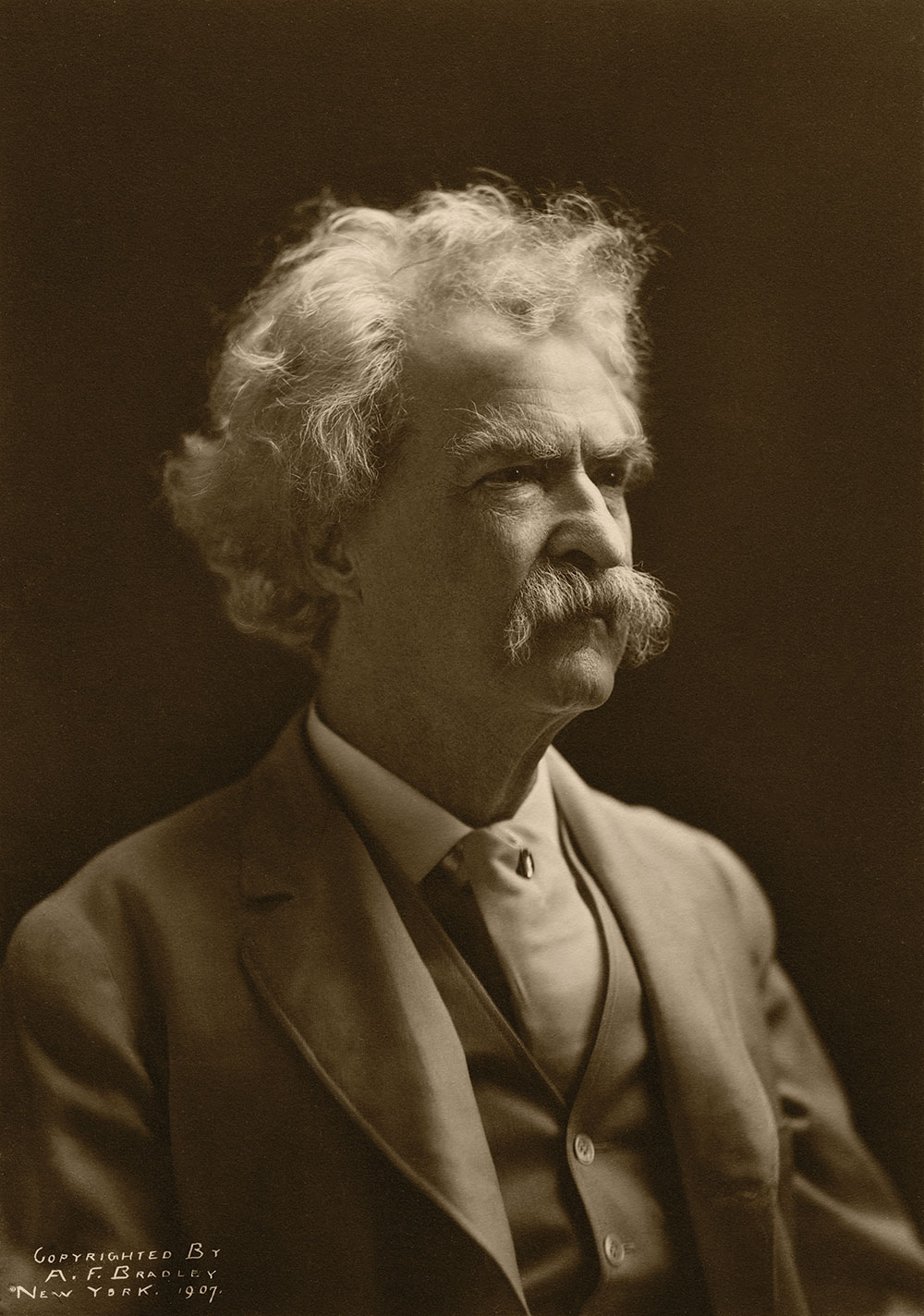

Legendary Nevadans: Mark Twain

Summer 2022

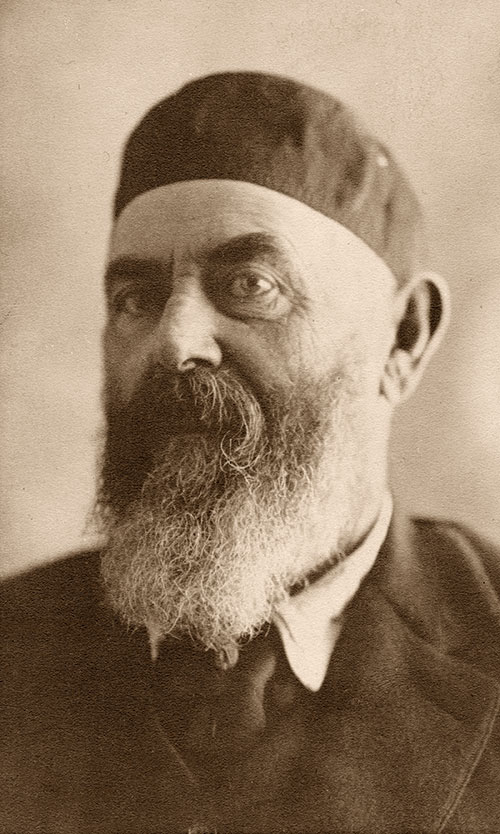

Samuel Clemens becomes Mark Twain.

All Nevada is a stage, and cowpokes, artists, activists, and visionaries are the players in a drama centuries in the making. Whether born or raised, these special characters aren’t just Nevadans: they’re Legendary Nevadans.

All Nevada is a stage, and cowpokes, artists, activists, and visionaries are the players in a drama centuries in the making. Whether born or raised, these special characters aren’t just Nevadans: they’re Legendary Nevadans.

In 1861, Samuel Clemens was living his childhood dream as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi. The 25-year-old had established himself as a talented, respected navigator and earned a considerable salary of $70 a week (equivalent to about $2,000 today).

But that summer, Clemens knew his days as a pilot were over. The Civil War had just begun, and military blockades were undoing his livelihood. With few prospects in his home state of Missouri, a new opportunity suddenly appeared from his older brother.

NEVADA BOUND

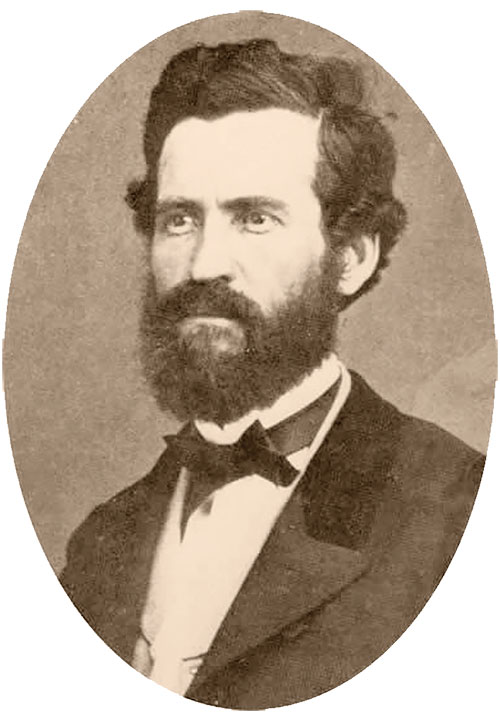

Orion (ORE-ee-un) Clemens was a lawyer who had campaigned for the election of President Lincoln. For his loyalty, Orion was appointed secretary of the newly formed Nevada Territory. Unfortunately, if he wanted the job, he would have to pay for transportation to Carson City. Samuel Clemens saw his opportunity and offered to finance the trip if his brother would hire him as an assistant. The two struck a deal and immediately set off west.

On Aug. 14, 1861, the brothers arrived in Carson City, dusty and travel-worn. Orion Clemens got to work managing affairs for the governor. Samuel Clemens, however, soon became bored with life as a secretary’s secretary. After a

few weeks, he resigned and set out to find fame and fortune.

SEEKING TREASURE

The word around Carson City was that a man could make a fortune buying and selling a timber claim. Samuel Clemens traveled to nearby Lake Tahoe and purchased a large piece of forest. To keep his claim, he would have to live on the land and build a fence around his property.

For a few weeks, he lived and worked on the shores of the alpine paradise, but his attention to the timber business slowly drifted. When he wasn’t building fences, Clemens was associating with mountain prospectors who often stopped by. These men told him of desert hills and lost mines hiding veins of rich ore. Clemens soon contracted gold fever—known locally as Washoe Fever—and the only cure was to strike it rich.

He traveled to Aurora—a young boomtown three miles on the Nevada side of the California border—and bought up a handful of claims. A month later, he heard tales of a new strike in a camp called Unionville. He arrived there in December and stayed in a small cabin for two weeks. When the strike turned out to be a bust, he returned to Aurora and worked his claim. When money ran short, he worked in the local quartz mill to fund his venture.

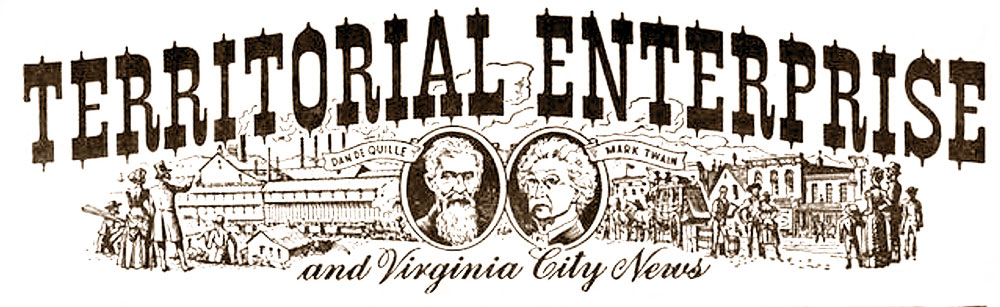

While in Aurora, Clemens spent his evenings writing articles for the “Territorial Enterprise” newspaper in Virginia City. Clemens had always been drawn to writing: before he was a riverboat pilot, he worked as a newspaper typesetter and even saw a few of his stories published. The articles sent from Aurora were humorous, semi-autobiographical accounts of life as a hard-luck miner. Rather than submitting the stories under his own name, he simply signed them as “Josh.”

CITY LIFE

Clemens would never find the lode that would make him a millionaire. After five months of hard labor, a letter arrived from Virginia City. Joseph Goodman—editor and owner of the “Territorial Enterprise”—wanted to know if “Josh” would like a job. The salary wasn’t large, but with a choice between sweating in the quartz mill or writing in Nevada’s biggest boomtown, Clemens elected to pack his bags and walk the 90 miles back to civilization.

In September 1862, he arrived in Virginia City. While only three years old, the town was undergoing a remarkable transformation from tent camp to cosmopolitan city that boasted fine restaurants, French cafés, and grand theaters. In the West, it was rivaled only by San Francisco, and Clemens fell in love with it.

The young reporter enjoyed his new lifestyle. He would go to sleep at dawn, awaken at noon to a large breakfast, cover the streets and saloons, then write into the early morning. When he wasn’t working, he enjoyed the privileges of the upper crust and mingled with the town’s aristocracy at operas and galas.

It was not difficult for Clemens to round up the town gossip and spin it into news. Clemens’s magnetic personality endeared him to the public; he was personable, a natural storyteller, a born entertainer, and—as he would readily admit—something of a lovable scoundrel. His flashy dress and signature cigar dangling from his lip gave him an air of distinction. He was a born writer, and his affinity for humor and fun, colorful language delighted readers. But a propensity for spinning yarns made him a West Coast star.

TALL TALES AND HOAXES

TALL TALES AND HOAXES

One of his most famous hoax articles, titled “Petrified Man,” reported the discovery of a man whose body had turned to rock. While it appeared like a news article with expert opinions, scientific facts, and a detailed timeline of the investigation, the story was entirely fake. For readers who caught onto the joke, the stories were entertaining, but when other folks were fooled, they became hilarious.

Virginia City readers were delighted when these hoaxes embarrassed people in power or fooled other newspapers into reprinting them as fact. After a San Francisco newspaper exposed a business in Nevada that had falsified its earnings, Clemens plotted his revenge. The San Francisco papers, he lamented, never talked about corruption in their own city. He vowed to trick the papers into printing a story that would both embarrass them and expose a California business.

Clemens wrote about a man who had confessed to murdering his wife and nine children with an axe. The man said he did it because he had lost his savings by investing in the Spring Valley Water Company in California. Although there were plenty of outlandish details to indicate it was all a hoax, the graphic story was reprinted in San Francisco papers.

Clemens endured severe public backlash for his trick. When he saw his own paper’s reputation was now tarnished, he offered to quit. Goodman—his unflappable editor—rejected the resignation, stating, “We can supply people with news, but we can’t supply them with sense.” Eventually, the anger passed, and now everyone knew about the young writer in Virginia City.

A NEW NAME

By winter of 1862, the young man was an accomplished journalist, yet still missed something every great writer needs: a pen name. In Aurora he was “Josh,” but that lacked gravitas and flair. Since arriving in Virginia City, he had been submitting his articles uncredited.

In December, Clemens was sent to Carson City for six weeks to report on the legislative session. He was not interested in this assignment, but he looked forward to spending time with his brother. Each day, he dutifully recorded the proceedings, then sent his news off to Virginia City.

On Jan. 31, 1863, Samuel Clemens sent his report of another dry day at the legislature. Below his dispatch, he finally wrote a name. Where it came from is unclear. Perhaps he used this name for his bar tab, but it could be a term called out by riverboat pilots to indicate safe water. Some believe it was the nom de plume of a friend back east. Regardless, he would carry it for the rest of his life. The writer was now Mark Twain.

On Jan. 31, 1863, Samuel Clemens sent his report of another dry day at the legislature. Below his dispatch, he finally wrote a name. Where it came from is unclear. Perhaps he used this name for his bar tab, but it could be a term called out by riverboat pilots to indicate safe water. Some believe it was the nom de plume of a friend back east. Regardless, he would carry it for the rest of his life. The writer was now Mark Twain.

Twain continued writing for the “Territorial Enterprise” into early 1864, but by spring, he was ready for a new adventure. He loaded a wagon and left Virginia City for San Francisco, though he would return to Nevada twice to perform lectures in 1866 and 1888.

Over the next few decades, Mark Twain would emerge as a national celebrity, and today he is considered one of America’s most cherished authors.