Yesterday: The Orange Rock Down Vegas Way

Summer 2022

An author reflects on the happy life of her hardscrabble family in the remote Nevada desert.

BY EVA DIAMOND WITH HER PAINTINGS

This story originally appeared in the Winter 1973 issue of Nevada Magazine.

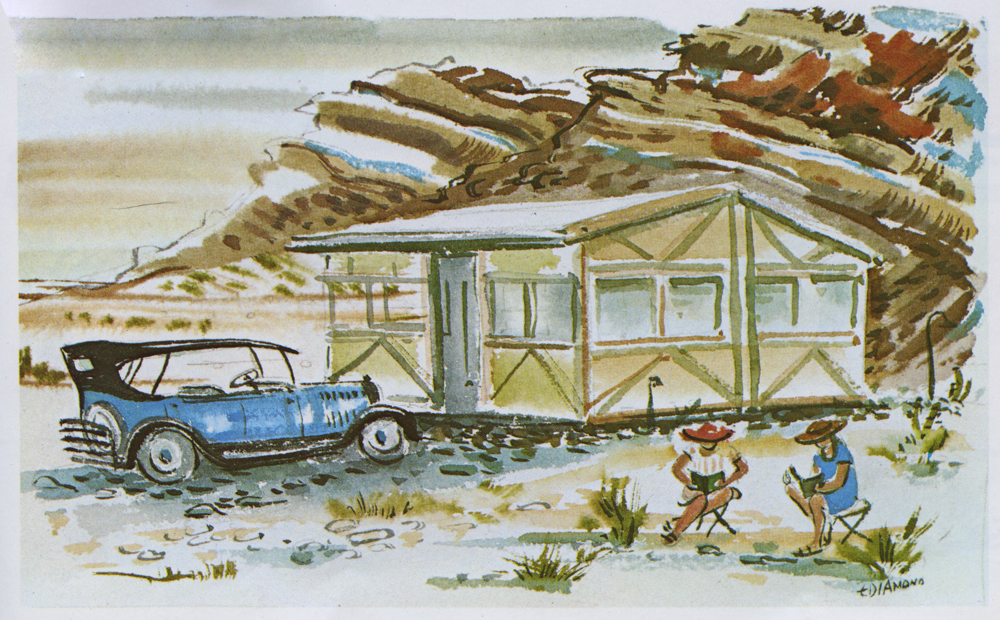

Las Vegas had wooden sidewalks when we moved to the desert. But before leaving foggy San Francisco my father, with the extravagance of a true miner, told us Nevada was a golden land with red skies and great castles built into purple rocks-where the earth shimmered in the sunlight and the sky moved at night. So it was glory day when we packed up our 1924 Studebaker touring car and took off for the promised land, or more precisely, the mine near Sandy Valley Dad was working with some old Alaskan sourdough friends.

I was only six, but I can recall .more clearly than last week-end Old Stoody’s side curtains flapping in icy winds over Tehachapi and our massive disappointment in the desert. We saw no castles, no red, no purple. But there were distractions. Paved roads had given way to a rocky, rutty single lane marked by tire grooves, hoof prints and a row of rocks lining either side. And even these markings wavered where we skirted large boulders and washouts. It was night of our third day when we reached Jean, Nevada, and left our “highway” for Sandy. Only now the road had diminished to a hazardous guess. Several times old Stoody wandered off into the desert, where the marking rocks had been washed out of line by cloudbursts. Dad got out with a flashlight to look for the road. Several times we all got out to move rocks from out path for as far as we could see in the headlights. And all along the way, we took turns holding the light while Dad patched and changed tires. Morning came before we covered the twenty miles from Jean to Sandy and the Palmer’s house, where we were to live until some beaverboard walling arrived for the little desert house my father was building near the mine.

We stayed all winter and into the spring in the Palmer’s dark cabin. I’m not sure even my father, who insisted that the only legitimate reasons for living on the desert were mining and tuberculosis, knew why that strange couple lived in Sandy. Mrs. Palmer always wore black and seldom spoke to Mr. Palmer, who never spoke to her. Anyway, theirs was a spook house. Mr. Palmer had decorated the front with drying carcasses of coyotes and bats, and out back, where two large piles of tin cans offered recreational possibilities, he skulked around shooting birds and hanging them on the clothesline near his garden. On the north side, a huge snarling dog was tied a few feet from two unmarked graves, one quite small with a little fence around it. So my sis Jo and I stayed on the south side throwing rocks at cactus and waiting for the earth to shimmer.

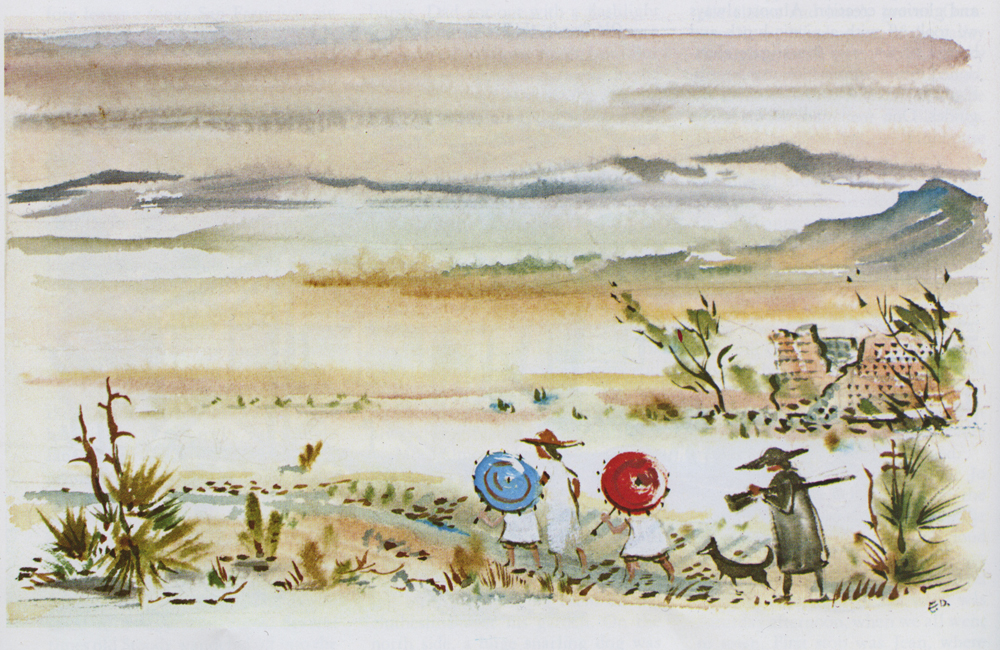

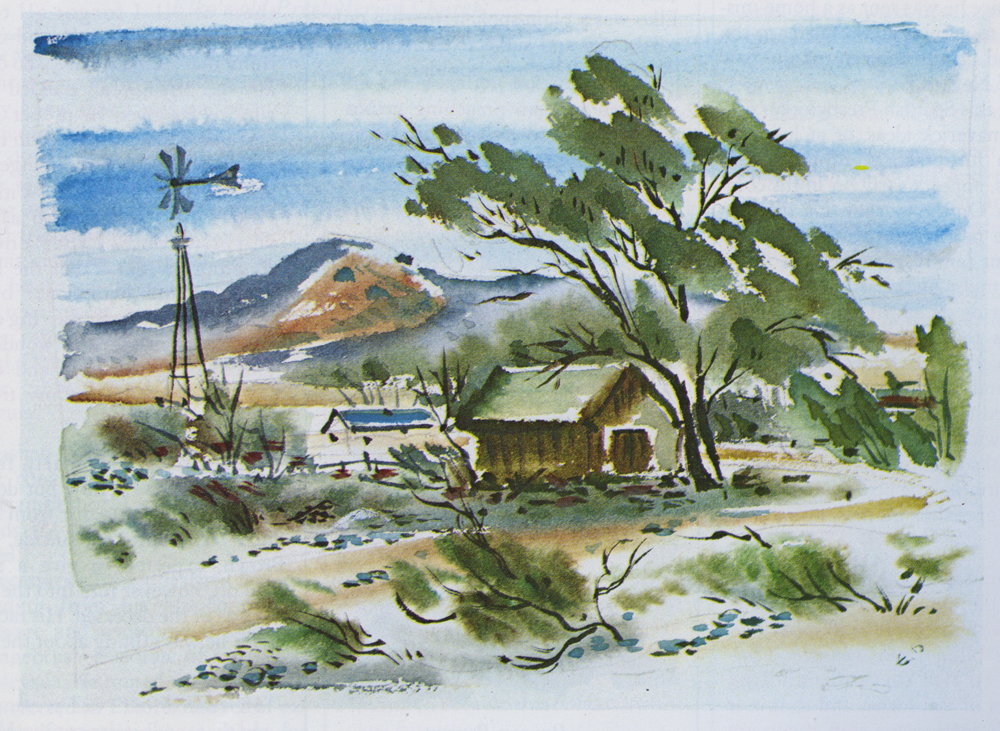

Sometimes we would gaze longingly across the valley at the Ewing place, with its trees, horses and windmill, but the Ewing boys were not interested in playing with two city types. We were not supposed to look at the only other house in the valley, a shack up the road near sotne tailings where two brothers were taking something out of the desert floor. I understood their names to be Essobee. Luckily, Mother liked to walk, and every day we took up our parasols and set off across the desert using for return markers pyramids of rusty tins, rockpile claims and lonely graves. Occasionally we hiked up out of the valley through a small pass into the rocky gorge where the mine was located. Sometimes Dad let us stand inside the mine so we could feel the blastings, but usually the mine, the bunkhouse and the mill pond were off limits, and we played around the frame of our new little house nestled under the bright orange rock that was to become my desert landmark. Most often though, our daily jaunts took us down into the valley past two old adobe bottle houses near some mesquite trees. Once in a while, Mrs. Palmer put on her big black straw hat, hoisted her shotgun under her arm and went along. She said she was protecting us from rattlesnakes; I didn’t see why she had to blast away at every rabbit and wild burro that moved.

Easily the best time of day for Jo and me was dusk, when we ran up the road far enough to see the pass to the mine, and waited for the moving cloud of dust that would materialize into Old Stoody, only car in Sandy. And easily the best time of the week was Saturday afternoon, when we all went to town. First stop was Jean, where Dad inquired about his beaverboard and fussed with the car, while Mother, Jo and I went into the tiny station for our weekly supply of “dirty” books. The volumes, all discards from the Los Angeles Public Library, were dirty indeed. Once I was denied HEIDI because it was so dirty one might get smallpox. The one roadside business at Jean was so evil we were never allowed inside. Nor were we permitted to go into the store at Goodsprings, where Mom and Dad shopped for kerosene and food, except once when a dust storm drove us in and my big sister knowingly pointed out a slot machine. But we loved Goodsprings. It was a real town with people, trees, horses, real houses and even a church. Sundays too, were good days, as the automobile was still a unique and glorious creation. Almost always we took off with a picnic lunch and bottles of water to investigate abandoned mining properties, using scribbled maps, rumors and hunches for guides. One week-end we made the forty-mile drive to Las Vegas, where Jo and I strolled the wooden sidewalks and looking past one swinging door saw to our delight men drinking whiskey in violation of the 18th Amendment. Another time, on our way to a rodeo, we drove through Las Vegas to a valley where hundreds of horses and cattle had drowned in a flash flood. Of course, every drive was half road hunting and tire changing.

Wild flowers came to the desert and tall grasses were springing from the graves by the time the beaverboard arrived and Dad completed our little house. We set up housekeeping with a kerosene lantern, a kerosene stove, a canvas desert cooler and a broom. Dad hammered together benches and a table, and acquired bedsprings for Mother and him. Running water was just outside the door, piped above ground from somewhere, and we started our own pile of tin cans in a nearby washout. Spirits ran high as Dad talked of assays and silenced all complaints with plans for around-the world cruises, first class. Every morning I ran out to see if rabbits had eaten my favorite cactus flowers.

But the real enchantment for this miner’s child was the big orange rock in the stony ridge behind the house. I knew it contained venadium, and for weeks I begged permission to scale the rocks and stake my claim. Finally one morning I was allowed to scramble up behind the Ewing boys, and found my rock to be not only gigantic, but flecked with “gold.” I staked my claim, laying small rocks to form a castle, and descended to the desert floor a full-fledged dreamer.

Reality was also improving. The Ewings gave us a dog named Carbo. My Aunt Alice visited from Washington, and had the grace to lie on the ground at night and say she saw the sky move with the flashing and diving of giant stars. Best of all, my sister and I found playmates, two girls, whose father Frank Williams, desert rat and Regent of the University of Nevada, had a solo mining operation out through the back of our gorge. Mrs. Williams was a former New England school marm, so it was not long before there was school for the four of us.

But the important lessons we were learning those desert days had little to do with arithmetic and spelling. We were learning how to “see” in a place where everything was noteworthy-the colors in a rock, the profile of a distant mountain, the texture of a flower. Any change in that uncluttered landscape-any change in sky or atmosphere-was an event. I had long since seen the earth shimmering as light rays were refracted by the heat of the desert’s surface. And my father had explained that the red in the sky and the purple of the rocks came not from pigments, but from light and from the talent of the viewer to see color. Dad told us that the fleeting nature of the desert hues made them all the more precious, just as rareness of the minerals in the rocks made them precious. The desert was a land of rare beauty as well as a land of rare minerals. I could have stayed there forever. But apparently, the ores were turning out to be more rare than the beauty, because one day, we packed up and left Sandy. I was allowed to take a good-sized chunk of the orange rock with me when Old Stoody headed back to the city, where most color comes from paint.

That was a long time ago and I had almost forgotten Sandy. But when my father died, a very old man well into a new dream, I began thinking about the desert and longing to go back and find my orange rock. Last summer on a drive home from a Grand Canyon river trip with my husband and daughter Carol; the chance came.

Quite appropriately, we drove from Arizona into Nevada at dusk through purple mountains and under very red skies. When we reached Las Vegas, however, I was forced to recall that the world had changed more in the years since I left Sandy than during the thousand years before. I had a same sense of disorientation at Jean, where the big truck stop is not even near the railroad tracks, and again the next morning when we drove out the paved, straight road to Goodsprings. But at least Goodsprings looked right. Except that everything had shrunkmountains, houses, trees and stores. Only the graveyard had grown. I felt like Alice in Wonderland. The dirt road from Goodsprings to Sandy was graded and too straight, although the mines along the way seemed familiar. But how would I know ours? I had no map. The mine had no name. I could hardly ask about an orange rock, if indeed we saw a living soul. I knew we would pass the turnoff to the mine before reaching Sandy.

Twelve miles from Goodsprings we left the rocks and descended into Sandy Valley, the emptiest expanse of land I had

seen in years. There was a house that could have been the Palmers, and across the way a place with windmill and trees. Perhaps the Ewings. The going operation alongside some· tailings would be an expansion of the Essobees enterprise. But there was nothing else. No adobe bottle houses. No pyramids of rusty cans, no claims, no graves. Only a sign advertising lots for sale. We turned back towards Goodsprings, and with sagging heart I studied the long row of jagged rocks bordering the valley. Then for some reason, my eyes kept returning to one pass until I could almost see coming through it a cloud of dust being pulled along by an ancient blue touring car. We drove as far as we could negotiate the rocks and washouts, and then walked. But as we approached, the pass seemed to diminish. It was just too small. Still, there was something about the airthe lightness and the sweetness -something about the long morning shadows of the cactus. I said, “If when we go through those rocks we find two large oval shapes, bright orange, half way up on the left side, we are there.” Carol ran ahead and returned with her eyes shining. We were there. The orange rock was in place, and just below it were scrambled rows of stones, foundations for a small house. And a very old rusted bedsprings. Across on the right was the mine. As Carol picked up a piece of orange rock to take home for her collection, she laughed, “The reason Mommy remembers this place so clearly is that there’s nothing much to remember.” If I hadn’t been crying, I’d have answered, “That’s what you think, honey.”