The Glory of Goldfield

Winter 2023

Remembering Nevada’s last great boomtown 100 years after its destruction.

BY CORY MUNSON

On a fine spring day in the year 1900, a rancher named Jim Butler was wandering the remote hills of south-central Nevada—looking for a stray burro, as the story goes—when he came across an outcrop of black-banded rock. Ever the hobbyist prospector, Butler picked off a few samples and headed back to civilization to get them evaluated. The assayer was shocked to discover that the black bands were pure argentite. Jim Butler had discovered one of history’s richest silver deposits.

BUTLER’S BONANZAS

Within a few years, Butler’s remote outcrop had transformed into the bustling boomtown of Tonopah. Until the rise of Goldfield, Tonopah was Nevada’s largest and richest city, peaking at around 10,000 souls. Butler was now a very wealthy man with the time and resources to do whatever he wanted. This turned out to be yet more prospecting.

Butler began outfitting young adventurers with supplies and munitions in return for a share of any claims they discovered—a practice known as grubstaking. One of his clients, a Paiute named Thomas Fisherman, had found gold some 30 miles south of Tonopah, but it wasn’t clear where exactly. More grubstake outfits were sent to find the mysterious mine.

In December 1902, two of Butler’s men went deep into the desert to locate the claim. Days into their journey, a great sandstorm assailed them, and they were forced to seek shelter in the nearby mountains. As they weathered the piercing wind, they were astonished to see particles of fine gold floating in a pool of water. Not only had they found Fisherman’s gold, but they were also standing on the site of the West’s last great gold rush.

A CITY IS BORN

Between 1904-1912, Goldfield’s mines were some of the highest producing in the world. The gold veins were so rich that they could be seen glittering by candlelight. In some tunnels, nearly every piece of ore had value, and tempted miners often stashed debris away in their clothes and in lunch pails. The pilfering was such a problem that federal troops were brought in to improve security.

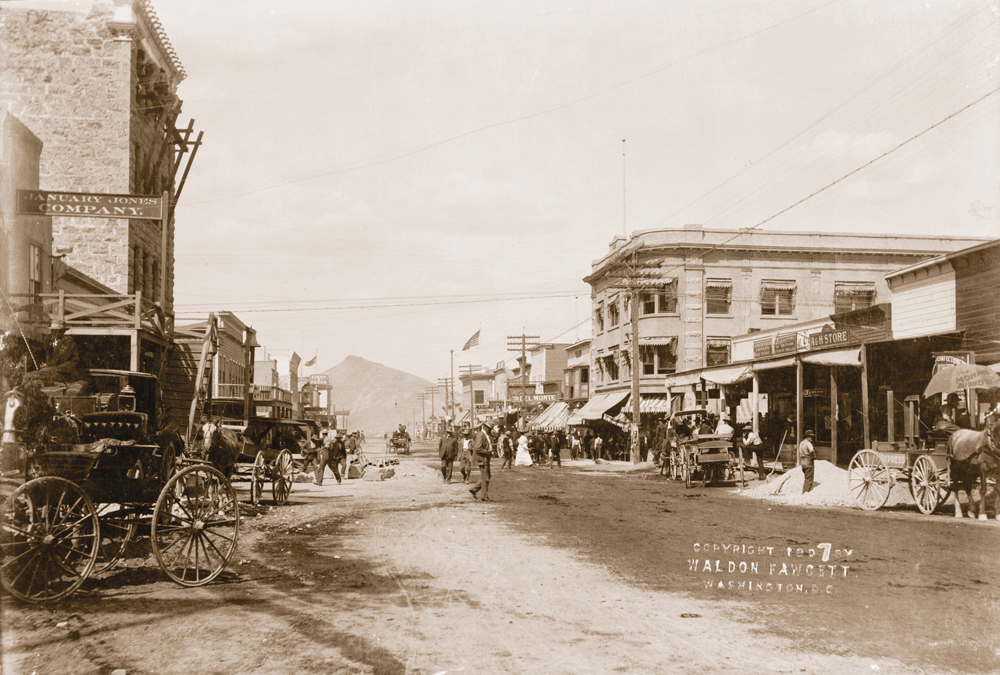

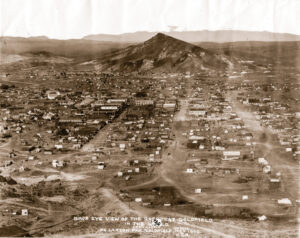

Above the caverns of unimaginable wealth, a great city blossomed. Early Goldfield looked like any other dusty, ragtag frontier town. But it was the 20th century, and the harsh, remote setting was no obstacle to expedited modernization. Instead of covered wagons, settlers arrived in an endless stream of primitive automobiles. Within a year of its founding, the town had telephone and telegraph lines. By 1905, a steam powerplant was powering homes and streetlamps and the city was connected to the national freight rail network, allowing bullion to be quickly exchanged for essential materials and luxury goods.

In 1907, Goldfield surpassed Tonopah as the largest city in Nevada with more than 25,000 residents. Within five years of its founding, the proud citizens of Goldfield had created a thoroughly modern metropolis that was Nevada’s cultural and financial hub. Its expansive commercial district boasted paved sidewalks, wide streets, and elegant stonework buildings including banks, union halls, luxury hotels, and department stores. As long as the gold flowed, there seemed to be no ceiling to progress. The town was hurtling toward greatness.

UP IN SMOKE

Goldfield’s development was wild and frenetic, but the city was still a boomtown, and boomtowns are ultimately unsustainable.

The decline began in 1912 when gold production dropped for the first time in Goldfield’s history—around 40 percent from the previous year. With the arrested growth, systemic problems—corruption, stock manipulation, strikes, and union busting—compounded the depression. On top of that, Goldfield’s rapid growth had come at a cost. While there were millionaires and mansions across town, ordinary citizens experienced inflation, limited real estate, and spotty utilities. The mines still produced—and would for another decade—but the spirit of the rush had left the town. The spell had been broken. People began to leave.

On the morning of July 6, 1923, Goldfield was home to around 1,000 residents—a fraction from its peak. Although significantly depopulated, its buildings were still there, unchanged since the bonanza years. It still looked like Nevada’s largest city—developed and magnificent like a mini-Manhattan—but nobody was home.

Although the empty storefronts and shuttered high-rises were a sad sight for those who remained, it turned out to be a good thing. Few people were in any actual danger when the flames arrived.

The fire started at 6:45 a.m. one block west of the Goldfield Hotel. How the blaze began is unclear, but it’s believed to have started at the house of T. C. Rhea after his Prohibition-era moonshine still exploded. Some residents believed it was an act of sabotage by rival bootleggers.

Early risers spotted the smoke, and the town was quickly roused. The fire brigade leapt into action just as the flames were spreading to an adjacent commercial garage. One car, belonging to a miner, was filled with dynamite. When it exploded, firebrands violently blasted out into the city, igniting spot fires. Worse, strong southerly winds blowing up to 40 mph threatened to carry the fire northward and directly into downtown. The situation was dire. In a last-ditch effort, firefighters raced across the street with more dynamite and began blowing up buildings to create a firebreak.

It did not work. The hot summer had turned the city into kindling. The conflagration jumped the street, overrunning the firefighters’ position and forcing them to retreat. Their equipment and hoses were abandoned and lost to the flames. At the same time, Goldfield’s decaying water infrastructure failed, and the city lost water pressure. The helpless residents could do nothing but watch as the fire grew into a 4-block wall of flames.

The fire burned itself out at around 3 p.m. By then it had taken two lives, 25 blocks, and more than 200 buildings, including most of downtown. More than 100 residents were homeless. Almost all the grandest buildings were now charred rubble. Surprisingly, one of the few structures to survive was the Goldfield Hotel, which was only a few dozen feet from where it all began.

The fire burned itself out at around 3 p.m. By then it had taken two lives, 25 blocks, and more than 200 buildings, including most of downtown. More than 100 residents were homeless. Almost all the grandest buildings were now charred rubble. Surprisingly, one of the few structures to survive was the Goldfield Hotel, which was only a few dozen feet from where it all began.

After the fire, Goldfield experienced its second major decline. For many, there was nothing left. Within a week, more than 300 residents had left town. A few years later, another fire wiped out what remained of the commercial core—except for, again, the Goldfield Hotel.

TODAY

It has been 100 years since the devastating fire, but Goldfield has survived. It is much sparser and quieter than it was, but after the rubble was cleared, life went on. People cleaned up, rebuilt, and got back to their lives.

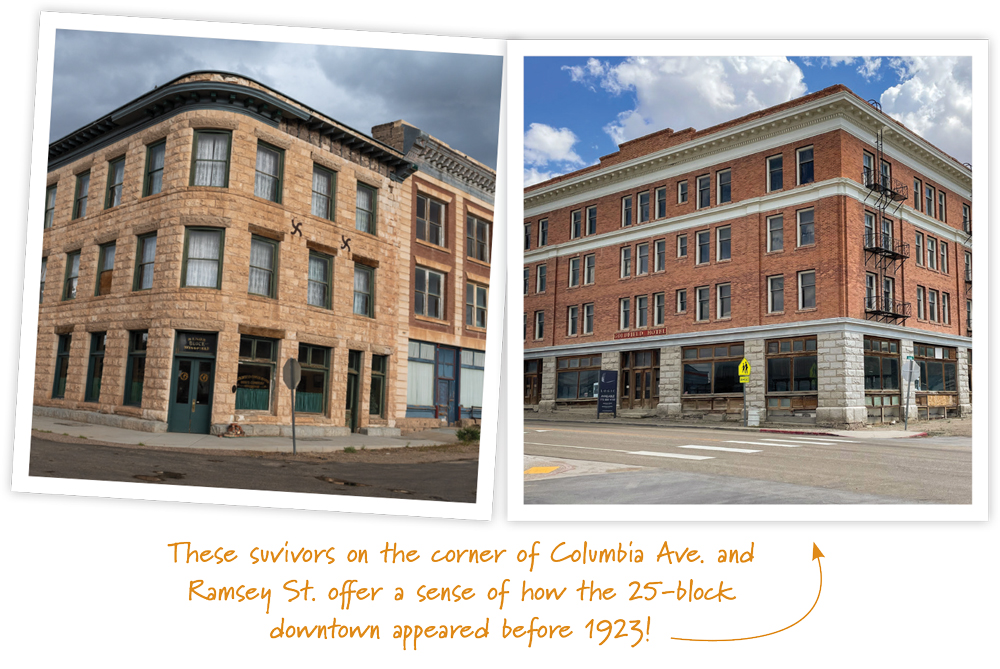

For decades, Goldfielders have work tirelessly to preserve what has been saved, and the fire’s few survivors are conspicuous landmarks that tell part of the town’s hidden history. If passing through, make sure to stop and explore the town. It takes a little imagination to see Goldfield as it was during the glory years, but an excellent walking tour map is available at the visitor center.

For a few incredible years, Goldfield embodied Nevada’s spirit of discovery and excitement. It is still here, and hopefully its richest years lie ahead.