Celebrating Jack Johnson

Celebrating Jack Johnson

The first black heavyweight champion’s 1910 defeat of James Jeffries in Reno comes full circle this July.

BY SHANE BORROWMAN | MAY/JUNE 2010

On July 4, 1910, Jack Johnson, who two years earlier became the first black boxer to hold the heavyweight title, beat former champion and white opponent James Jeffries in Reno. Although lesser known, Johnson’s triumph (and seven-year reign as champ) is as culturally important as Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a busy Alabama bus 45 years later. For this reason, Johnson-Jeffries is still regarded as one of the most famous heavyweight title matches, and only a last-second change of plans brought the event to Reno.

To give an idea of the buzz that surrounded the fight, Jack London, famously known for his fiction, reported on it—just as he had two years earlier when Johnson took the title from Tommy Burns in 14 taunt-filled rounds. “What…[won] on Saturday was bigness, coolness, quickness, cleverness, and vast physical superiority,” London wrote about Johnson in 1908.

That fight, staged in Australia, cost Johnson and his promoters $30,000, an unheard of sum at the time but the only payment Burns would accept for fighting a black man. The color line ran thick through American culture in the early 1900s, less than 50 years removed from the Civil War. Despite this, Johnson saw no reason why he couldn’t be the Heavyweight Champion.

Born on March 31, 1878, Johnson began boxing in his teens, sometimes working as a sparring partner and taking part in battle royales, events that pitted large numbers of young black men against one another simultaneously. Johnson was jailed after one such bout, not unusual in a time when virtually all boxing was illegal. While this was a minor offense, it would set Johnson on a course that would end in serious issues of crime and punishment.

When Johnson was a boy, John L. Sullivan transformed boxing. Sullivan, known as the “Boston Strongboy,” is recognized as the first champion of gloved boxing—a title he held from 1881-92. Famously, Sullivan offered to fight anyone, anywhere, any time, but that challenge did not include black fighters. Sullivan lost his title to “Gentleman” Jim Corbett in 1892, whereby Corbett also refused to fight a black opponent. This stance continued through the reigns of the next three champs: Bob Fitzsimmons, Jeffries, and Marvin Hart.

Black fighters and their promoters, who were denied access to the recognized title, named a World Colored Heavyweight Champion—a title Johnson claimed in February 1903 after beating “Denver” Ed Martin. Hart, meanwhile, was no Sullivan or Jeffries, and he lost his title to Burns in less than a year’s time. Although Burns would duck Johnson’s challenges for more than two years, he found himself in the ring in 1908 with a cunning Johnson, who delivered a staggering beating. Scheduled for 20 three-minute rounds, the fight—held in Sydney, Australia—saw Burns knocked down within seconds of the opening bell. Johnson constantly teased the crowd and taunted his adversary. To spare Burns the humiliation, police stopped the fight and filming in the 14th round.

At age 30, Johnson was the first black Heavyweight Champion, a title he would hold until 1915, despite a string of “Great White Hopes” (a term used in the day for white challengers to Johnson). In 1910, Jeffries came out of retirement—even though he had ballooned to more than 300 pounds. For the Johnson-Jeffries fight, each man received a $10,000 signing bonus, with a payout of $101,000 guaranteed to the winner. Such numbers were unthinkable for most, but not promoter Tex Rickard, a P.T. Barnum-like figure. Rickard even had a special arena constructed in San Francisco, where the fight was originally scheduled to take place on July 4, 1910. But political pressure was brought to bear upon the Governor of California, James Gillett, by religious groups that viewed boxing as brutal and unfit for civilized society. On June 6, Governor Gillett canceled the fight.

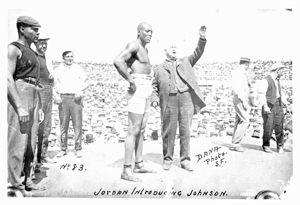

Rickard acted swiftly and moved the highly anticipated bout to Reno, where prizefighting was legal and several east-west railroads met. Nevada Governor Denver Dickerson demanded an assurance from Rickard that the fight be fair, not fixed. Reno’s population in 1910 was 12,000. Into this town poured at least 15,000 fans, virtually all white and wagering on Jeffries at 10-to-4 odds.

From the opening bell, a snickering Johnson implemented his customary style: he counter-punched, blocked punches, and tied his opponent up—a technique almost identical to Corbett’s when he took the title from Sullivan. Round after round, Johnson pounded on Jeffries and played with the crowd and Corbett, who was working in Jeffries’ corner.

Even now, a century later, footage of the fight shows the inevitability of its outcome, as well as any front-row seat, would have. By the end of the 14th round, Jeffries’ nose was broken, and he was covered in his own blood. In the 15th round, Johnson knocked Jeffries down again and again—punishment that the undefeated Jeffries was unaccustomed to. Conversely, Jeffries’ corner threw in the towel, and a grim white audience filed out in near silence. The victory spurred intense, yet short-lived, race riots across the nation, a precursor to the Civil Rights Movement triggered by Parks in 1955.

After besting Jeffries, Johnson held the heavyweight title for nearly five more years, losing to Jess Willard in April 1915. One of the greatest boxers of all time, Johnson’s legacy would be tainted by the same racism that kept him from his rightful place as Heavyweight Champion for so many years.

Johnson had, from the beginning of his career, made no effort to hide his relationships with white women—all of whom were, at one time or another, referred to publicly as “Mrs. Jack Johnson.” In 1912 and 1913, Johnson was charged with violations of the Mann Act, which forbade transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes. The evidence was shaky and the case weak (especially because it was built upon alleged crimes that occurred before passage of the Mann Act), but Johnson was convicted. Rather than turn himself in, he fled the U.S., living in exile for the next seven years. Returning in 1920, Johnson was taken into custody at the Mexican border. He served his sentence, returned to boxing, and finally retired from the sport in 1938. In 2009, Senator John McCain, among others, asked President Barack Obama to sign a presidential pardon for Johnson.

In that same spirit, boxing fans and aficionados will gather in Reno on July 2-4, 2010 to honor Johnson. The eventsinclude a Pardon Dinner celebration, multimedia presentation titled “Fighting for the Soul of America,” celebrity panel discussion, continuous showing of the original 1910 fight film, autograph sessions with past heavyweight champions, and professional boxing at the Reno Events Center. “The whole boxing community wants Obama to move forward with the pardon,” says boxing historian Gary Schultz, who is organizing the event. “It’s long overdue, and there isn’t a more appropriate time than now as we approach the 100th anniversary.”

“It’s going to be a boxing summit,” adds Terry Lane (son of longtime boxing referee and former Washoe District Judge Mills Lane) of Let’s Get It On Promotions. “We’ve had a tremendous response from people across the country and around the world.”

UPDATE

The Nevada Historical Society will host a free lecture by former State Archivist Guy Rocha as he presents the program “Long Forgotten, Later Found: The Johnson-Jefferies Fight Site.” The presentation will be held May 22 at 1 p.m. in the society’s Reno History Gallery.

Click here to subscribe to Nevada magazine.

Related Stories

“London is not Reno,” by Daniel J. Demers

“Johnson-Jeffries exhibit hits Reno,” by Teresa Moiola

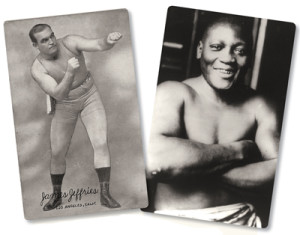

James Jackson Jeffries

Nickname: The Boilermaker

Height: 6’0”

Reach: 76.5”

Born: April 15, 1875

(Carroll, Ohio)

Record: 20-1-2 (16 KO)

Jack Johnson

Nickname: Galveston Giant

Height: 6’1.5”

Reach: 74”

Born: March 31, 1878 (Galveston, Texas)

Record: 78-7-14 (44 KO)

EVENT

100th-Year Anniversary Celebration

When: July 2-4

Where: Reno

Contact:

johnsonjeffries2010

letsgetitonboxing.com