Cycle Nevada

Fall 2020

A first-person account of Highway 50, as experienced from a road bike.

BY BILL HATFIELD

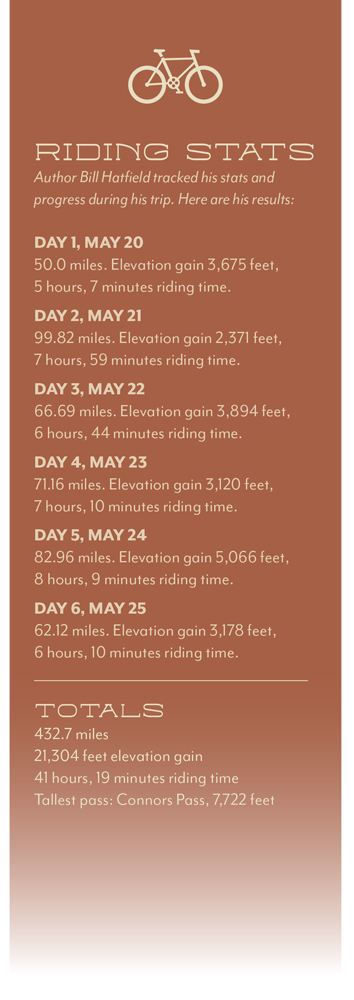

My friend Adam Stone and I finished the 13-mile, 2,500-foot climb to Virginia City just after 7 p.m. It was the biggest hill I had ever ridden, and my bike was loaded with camping gear, food, and supplies for a six-day trip. I had feared not making it up Geiger Grade at all, but now, heading for our campsite outside the former boomtown, I was cautiously optimistic I could ride all the way across Nevada.

Earlier that day, as the westerly wind picked up as it does on Reno afternoons, I waved goodbye to my family and pedaled into it. Seven miles west in Verdi, I turned onto Bridge Street from Old Highway 40, crossed the Truckee River on a one-lane bridge and stopped at an iron obelisk that marked the California border. If I was going to ride my bike across Nevada, I wanted to do it from one state line to the other. I rode to south Reno, where Adam was finishing work, and together we headed for Virginia City.

I have always craved the intimate relationship with place that traveling by bike provides. Open space has always been my drug of choice. What better way to get my fix than by cycling across Nevada?

INTO THE GREAT WIDE OPEN

That night we camped in Sixmile Canyon near the remnants of a cyanide mill, where tailings from the nearby mines were visible. The next morning, after freewheeling out of the steep, chilly canyon, we joined U.S. 50 and began the arduous ride past alkali flats and across the massive Carson Sink, part of ancient Lake Lahontan. We hoped to camp at Middlegate that night, making it a 100-mile day.

We stopped for what would have to pass for provisions at a gas station outside Silver Springs, then continued to Lahontan Reservoir, where we snacked under cottonwoods and watched pelicans fishing at the mouth of the Truckee Canal. Flowing 32 miles from the Truckee River, the canal begins at Derby Dam, which was completed in 1905 as the first project of the U.S. Reclamation Service (known now as the Bureau of Reclamation).

Later, we passed through Fallon, riding on surface streets along the north end of the Naval Air Station before rejoining U.S. 50. Before long we pulled into Grimes Point Archaeological Site, where more than 1,000 petroglyphs adorn the nearby boulders. The historical marker says the petroglyphs “were of magico-religious significance.” As we rested, at least a dozen Navy jets tore across the sky and I wondered what kind of magic the folks who made the petroglyphs would think was at play here today.

By the time we passed the turnoff to Sand Mountain Recreation Area, where hundreds of RVs and trailers dotted the landscape near the faraway dunes, the road traffic had all but disappeared. Even though we had already covered 125 miles, I felt like only then were we beginning the ride. Entering the topography of the basin and range, we would cross a wide valley, then pedal over a long and slender mountain range, where a white-knuckled descent would bring us to the next basin. We had 300 miles and 13 mountain passes to go. I sat up straight against the hot wind, lifted my hands off my bike, and glided along the middle of U.S. 50. Now we were cycling Nevada.

We crossed Sand Springs Pass and Drumm Summit as we followed the Pony Express route for the remainder of the day. Around 6:30 p.m., we rolled into Middlegate Station, and my odometer read 99.8 miles. But who’s counting? I’m calling it a hundred.

To ride in the Nevada desert, you must plan according to the resources. Much like the Pony Express riders, we would stop each night somewhere we knew we could find shelter and resupply. Middlegate blessed us with its free camping, flush toilets, hot food, and cold beer.

TIME CRUNCH

Leaving early the next morning, we headed for breakfast at another Pony Express stop, Cold Springs Station. Later, we stopped on New Pass Summit for a break, and we first encountered the millions of Mormon Crickets that we would see repeatedly for the next two days.

I avoided the crickets when I could ride slowly and watch the road just in front of me. On some descents, though, at upward of 30 m.p.h., it would be dangerous to hesitate or swerve, and an occasional crunch was inevitable. At Mt. Airy Summit, where the crickets were cannibalizing their smashed brethren along the highway, we didn’t stop.

We raced down the hill and across Reese River Valley, trying to outrun an approaching storm. By the time we made the short but steep climb into Austin, we were beat, and we decided to skip camping and get a motel. An old but comfortable $60 room at the Lincoln Motel sufficed, and we enjoyed calzones and some cold beers at the nearby Owl Club before calling it a night.

Crossing Austin Summit and Bob Scott Summit in the morning, we felt confident in our decision to not camp. The ground in the conifer-dotted campsites where we would have slept was still frozen solid.

It’s no secret that Nevada’s landscape is one of large scale. Traveling by bike, I repeatedly found it difficult to estimate distances. One stretch of road after Hickison Summit seemed to go on forever. Was it 10 miles or 20 across the valley? Hindered at times by a pesky crosswind, we spent hours on a single, 28-mile length of road. There we crossed paths with the only other cyclist we would see. He was a thousand miles into a ride from Wyoming to California, and we were the first cyclists he had encountered as well.

It’s no secret that Nevada’s landscape is one of large scale. Traveling by bike, I repeatedly found it difficult to estimate distances. One stretch of road after Hickison Summit seemed to go on forever. Was it 10 miles or 20 across the valley? Hindered at times by a pesky crosswind, we spent hours on a single, 28-mile length of road. There we crossed paths with the only other cyclist we would see. He was a thousand miles into a ride from Wyoming to California, and we were the first cyclists he had encountered as well.

On our fifth day we would cross four mountain passes over about 80 miles. As we climbed steeply out of Eureka over Pinto Summit, the cold, steel guardrails creaked and popped in the morning sun. By lunchtime we had crossed Pancake Summit and Little Antelope Summit, stopping at each to rest in juniper and pinon shade. After Robinson Pass, we cruised the day’s final miles past Ruth Mine and into Ely, where we cycled through a McDonald’s drive-through, then camped outside town at a KOA campground.

HOME

On our final day only two passes remained. On the descent from Connors Pass we first laid eyes on 13,063-foot Wheeler Peak. In Spring Valley, the dozens of wind turbines indicated a difficult ride into the wind awaited us, and we struggled through the valley before climbing Sacramento Pass, the steepest of the trip. Eventually we were down the other side and pedaling across the last valley. Without fanfare we pulled up to a large sign that colorfully indicated we were in Utah, and we were finished.

Nevada is many things, but lonely is not one of them. To be on the empty road is to be a part of state’s geography and culture. One of the things I love about riding my bike is witnessing a landscape as it unfolds. We experienced every inch of road between California and Utah. Every mountain pass revealed a unique picture, a new angle with which to think about the landscape we call home.