Discovering Nevada Through its Desert Caves

Fall 2021

State’s subterranean world reveals the ancient history of the Great Basin.

By Cory Munson

In 1885, Absalom Lehman was riding south of his remote ranch near the Nevada-Utah border. As he worked his way into the verdant mountains near his homestead, the ground suddenly gave way and the horse and rider plunged through a chasm in the earth. Recovering from the fall, Lehman rose and beheld a vast cavern of geological wonder.

The tale of Lehman stumbling upon Nevada’s most famous cave is rarely retold the same way: the horse fell but not the rider, the ground broke but no one fell, there was no horse. In the version told to me as a child, someone was kind enough to winch the horse back out of the ground, and it lived a long, happy life.

For all its splendor and history, Lehman Caves is but one such treasure in this state. There are 40 known caves in Great Basin National Park alone, and in Nevada there are an estimated 30,000 caves, grottos, and alcoves. By exploring these subterranean sites, we can uncover the history and hidden beauty of the Great Basin.

A WATER-FILLED BASIN

Ice reigned over our planet 20,000 years ago. Present-day Canada and the northern U.S. were pressed under 2-mile-thick glaciers, sea levels were 400 feet lower, and the average global temperature was 46 degrees Fahrenheit.

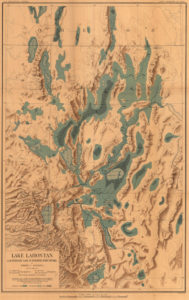

The Great Basin was a different place. There were glaciers, but those were nestled in the high mountains. The ice age in Nevada was better marked by a wet, rainy climate. Because the Great Basin has an elevated perimeter, water cannot escape to the ocean. Instead, the precipitation fell into the valleys, forming lakes. In northwestern Nevada, these lakes merged to create Lake Lahontan. At its peak 12,500 years ago, Lake Lahontan had a surface area greater than Lake Ontario.

When the ice age ended, the climate in the Great Basin became hot and dry, and the lakes began to evaporate. While the water disappeared, the minerals remained and turned the water brackish and rich in calcium carbonate. The mineral dense waves from these dying lakes lapped over shoreline rock and gravel, deposited the calcium carbonate—which cemented everything in place—and formed tufa.

In a valley in western Nevada, waves ate away at the hillside beneath the tufa and formed a cave roof. This is where Hidden Cave’s story begins.

HIDDEN CAVE

Eleven miles southeast of Fallon, Executive Editor Megg Mueller and I meet our tour guide Joe Allen at the Hidden Cave trailhead.

Joe carries a wooden pole as both walking stick and rattlesnake deterrent. Joe—a member of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe—is an expert on the area’s ecology and history as well as a craftsman: he creates duck decoys from tule reed.

We start up the 0.7-mile trail which loops through a U-shaped valley. Near the valley floor, Joe points out a petroglyph—a salamander—etched into a weathered stone.

“These artifacts,” he says “are 1-2 thousand years old. They were made when this valley was a wetland.”

We hike further up the hill, and Joe stops us at another group of petroglyphs. He explains that these are older than the salamander. Petroglyphs were made near water, which meant that these were made when the shoreline was higher and the hill was an island on a lake.

“Before that, 12-13 thousand years ago, this entire area was underwater; Lake Lahontan was 600-feet deep,” he says, sweeping his hands at the mountain ridges around us.

We look out into the surrounding desert of scrub brush and white playa. It strains the imagination to see a lake dotted with boats and the smoke from shoreline villages. It’s nearly impossible to imagine the same landscape completely underwater.

We reach the cave entrance, and Joe beckons us inside where we crouch through a low opening.

“It’s called Hidden Cave because it’s hard to find,” he says. “Back in the 1920s, some boys were up here looking for treasure. There was a rumor that a stagecoach robber had stashed his loot in the area. After a while, the boys got bored searching and began rolling boulders down the hill. They noticed some boulders were disappearing into the hillside.”

The cave opens into a high ceiling. Floodlamps illuminate the cave, and a hint of ammonia lingers in the air. Joe explains the smell: bat guano.

“After the cave was discovered, a man named McRiley mined bat guano out of here and sold it to fertilizer producers. To get to it, he had to excavate dozens of feet of soil out of the entrance. He left everything in a big pile outside which included what he called ‘Indian junk’.”

We ask if there are any bats left in the cave, and he assures us there haven’t been any for quite some time.

Joe takes us down a narrow staircase built by archaeologists in the mid-20th century. We are now standing on the original cave floor first formed around 21,000 years ago. A large cross-section cut in the wall is filled with pins and tags which date distinctly colored layers in the soil.

The soil layers are more recent as we move up the wall: beach gravel 10,000 years ago; gray ash from the Mazama volcanic eruption—the Cascades’ largest eruption in the past million years—6,900 years ago; human occupation 3,800 years ago. There is an atlatl hunting weapon sticking out from that layer.

We leave the cave, and Joe locks up the entrance. As we walk back to the cars, Joe points out where a sand embankment was mined off the hill a few decades ago. This caused waterflow to be diverted, which carved ravines in the soil and damaged the trail, vegetation, and wildlife habitat.

“This is a fragile environment,” he tells us. “Little changes like a missing embankment don’t just affect the surrounding area: they can change the balance of this valley which, in turn, affects the next valley and so on.”

We look up at the hill hiding the cave—once a marine floor, then an island, then a wetland, then a desert—and take his meaning.

To schedule a tour of Hidden Cave, visit the Churchill County Museum’s website at ccmuseum.org/hidden-cave-tours.

ALONE IN THE MOUNTAIN

Our next destination is Goshute Cave. Megg and I spend the morning rattling down a dirt road in northern White Pine County. As we drive, we jokingly point out the ranches we’ll call on when one of us gets stuck in a tunnel.

Our road takes us into mountain foothills and ends at a wooden gate. We peer up the unreasonably steep half-mile trail—no switchbacks to be found here. A circular shadow—an entrance into the mountain—stares back.

The hike to Goshute Cave is grueling and requires frequent stops in sparse shade, which are spent preventing helmets, backpacks, and water bottles from tumbling back down the hill. The hike ends with a climb up a smooth rock slope. I stare blankly at this rock face and wish I had brought a rope and a person who could climb up and tie it off for me.

Once atop, I catch my breath and witness the stunning view of Steptoe Valley. I turn around to inspect the large cave entrance when—to my horror—I see that it is nothing more than a shallow rock shelter. Panicking, I yell down the hill to ask where the cave is (as if Megg had something to do with this). She tells me to keep looking. Indeed, a few feet from where I am is the low, narrow entrance into Goshute.

Megg is still working her way up the hill, but the afternoon heat is becoming unbearable, and our time here runs short. We decide—in a conversation held entirely through yelling as I have no clue where she is in the forest below—that I should go into the cave alone to take pictures.

I don’t stray far into Goshute—just enough to get away from the natural light. Goshute is a large cave with enough passageways to keep an experienced caver occupied for the afternoon.

The tunnel immediately plunges downhill, and the cave floor is a powder-like dust which lingers in the air at the slightest disturbance. It is exhilarating and terrifying to walk into the blackness beneath a mountain. The knowledge of complete self-reliance begins as a burden; if my equipment fails or I get lost, I’m done. But these thoughts are replaced by a fascination in things that are so unfamiliar in the world above: alien formations, a serene, pure silence, and that darkness at the end of my headlamp’s range which seems to call out ‘aren’t you curious what’s down here?’

My time is up. I emerge blinking in the sunlight and am thankful for the summer heat. As I descend the hill, I am already thinking about my return trip. Next time, I’ll leave for the cave at dawn. Next time, I’ll bring more climbing gear, including a rope, and probably another couple of flashlights.

I feel the thrall of the exploration and the opportunity for discovery.

Maybe I’ll bring a horse.

CAVING 101

Dr. Louise Hose heads Northern Nevada’s chapter for the National Speleological Society, an organization who’s continuing mission is three-fold: exploration, conservation, and cave science. Those interested in caving can pay a membership and join the organization in its goal to better understand the nation’s cave systems.

“I love the combination of physical and intellectual challenges,” says Dr. Hose, “I have always been attracted to caves that are difficult to explore, rarely visited, and present scientific questions to be answered.”

“Many people view caves as an opportunity for adventure, but those people are generally better served by going on guided trips with people who can facilitate the adventure,” she cautions. Indeed, conditions during exploration can be difficult, if not dangerous. Bracingly tight squeezes, confounding labyrinthine twists, sudden drops, and dead ends are all bundled in the experience.

For this reason, most caves are not openly advertised. This policy serves to protect inexperienced explorers and the cave’s natural history.

ANCIENT WATERWAYS

Unlike shoreline tufa caves which can form in just 20,000 years, many caves in Nevada formed over millions of years.

The caves that appear in our mind’s eye as spindly, toothy tunnels are hypogenic caves. These caves form when warm, slightly acidic water courses through porous rock (in Nevada, this is generally limestone). Over millions of years, this flow erodes the rock and leaves river-like tunnels in its wake. When the water table drops, or the land is pushed up into a mountain, the water drains from the system and a dry cave is left behind. Lehman Caves—formed 8-10 million years ago—and Goshute Cave are examples of this process.

BE PREPARED

- Caves should only be explored with an experienced guide and in groups.

- Know before you go: do research.

- Tell someone where you are going and when you’ll be back.

- Get permits and permission when necessary.

Learn more about the National Speleological Society at caves.org.

Family Friendly Caves

LOVELOCK CAVE

Lovelock Cave is one of the most historically significant sites in North America. The cave served as a storage area for the Northern Paiute since 2580 B.C.E. and remained untouched until 1911 when it experienced damage from guano miners and rudimentary archeologic digs. The cave is located 40 minutes south of Lovelock and is easily accessible by a short trail and viewing deck.

TOQUIMA CAVES

Toquima Caves is a large rock shelter located one hour southeast of Austin. Toquima is an important cultural site for the Western Shoshone. The cave is home to some of the most remarkable pictographs (pigments on rock) in the West, which date between 3,000 and 1,500 years old. The cave is reached by a short hike and can be viewed through a protective barrier.