The Sagebrush School

Fall 2021

Nevada’s first generation of writers and journalists ushered in a golden age of literature in the West.

BY CORY MUNSON

On a cold December night in the town of Mormon Station, two men slotted the final components of their printing press into place. Their press assembled, they pulled out their letterboxes and set up, letter by letter, six columns of text. With everything in place, they ran ink over the press plate, loaded a blank sheet of paper, and pressed.

Although the two printers in that drafty winter shack could not have anticipated it, that first pressing served as the catalyst to a remarkable phenomenon in American literature. Very soon, the sparsely populated Great Basin Desert would be home to a strangely disproportionate number of talented novelists and journalists who captured American expansion during its feverish peak. Known for their wit, humor, truth-stretching, and blistering criticism of corruption, this loose association of writers is today known as the Sagebrush School.

A NEW KIND OF TOWN

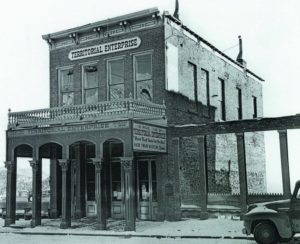

Nevada’s first newspaper—”The Territorial Enterprise”—was well-timed. Within a year of its 1859 founding, a rich vein of silver would be discovered at The Comstock Lode, leading thousands to head into the Great Basin. Booming mining camps filled the valleys on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, and such communities as Virginia City, Gold Hill, and Dayton became makeshift metropolises.

Nevada’s first newspaper—”The Territorial Enterprise”—was well-timed. Within a year of its 1859 founding, a rich vein of silver would be discovered at The Comstock Lode, leading thousands to head into the Great Basin. Booming mining camps filled the valleys on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, and such communities as Virginia City, Gold Hill, and Dayton became makeshift metropolises.

The sudden influx of immigration was remarkable—even blistering—but while other parts of the West also experienced large-scale immigration, early Nevadan communities were different. Those who came were not settlers in the general sense: their aim was to get rich and get out.

The towns were also not small. The hard-scrabbling prospector who panned a stream with his burro sidekick was not likely to find much success in Nevada. Unlike the California gold rush a decade earlier, ore extraction at strikes like The Comstock Lode required the collaboration of many.

Along with miners and laborers, wealthy speculators, lawyers, surveyors, and engineers were among the first residents in the towns. Many of those who came expected a cosmopolitan lifestyle and weren’t going to give up their East Coast luxuries: theaters, opera houses, billiards halls, saloons, and high-quality newspapers.

At the onset, corruption reigned in the remote territory. With so much wealth pouring from the mountains, powerful barons arose who could influence law enforcers and lawmakers. Silver-spooned mine speculators could drum up investment in a project they knew to be worthless. Early Nevada was known as the “rotten borough.”

In this lawless Petri dish of transients, boomtowns, treasure, and opportunity, the Sagebrush School was born.

FRONTIER JOURNALISM

The writers who came to The Comstock sought wealth, fame, and excitement; they too chased the next big strike as they hauled their printing presses from mining camp to mining camp. On the East Coast, their talent might have been diluted in the major population centers, but here their sway on public opinion was supreme during the half century the movement was active.

The term Sagebrush School is a modern construction, which reflects that these writers shared commonalities in both background and style. Nearly all were well educated, known to reference Shakespeare or Homer, but were also fond of blending the vernacular of the common folk into their works. They were often prolific, many starting their own papers that cranked out multiple editions per day. While they worked in journalism for the paycheck, they also pursued novels, published poetry, and wrote non-fiction including history and biographies.

In a society where everyone scrambled to get their own, the writers saw themselves as the voice for humanism and morality. They publicly arraigned villains and applauded heroes who stood up for their principles, even if that meant circumventing the law. They were skeptical—even critical—of the justice system and were not afraid to call out rampant corruption. Had they seen the films of John Wayne or Clint Eastwood, they would have sanctioned the extrajudicial justice employed by the characters they often played in pursuit of doing the right thing.

Finally, many in the writers were known for their hoaxes. At a time when public officials and journalists could find their opinions altered for a price, misinformation and downright lies were easily printed. In response, writers in the Sagebrush School would often publish stories that appeared true on their surface, but scrutiny would reveal the story was a fabrication. These hoaxes were presented for entertainment, but there was also a didactic element attached to them: by creating nonsense stories that appear true, they might teach the public to pay closer attention to what they were reading.

One famous example of the hoax is Dan De Quille’s article “Solar Armor,” which regales readers with reports of an inventor who constructed an air-conditioned suit. The article supplies interviews and scientific details, giving it a voice of authenticity, but readers are tipped off that it’s all been made-up when he reports the invention was too successful: the man was found frozen solid in the desert with an icicle growing from his nose.

RENNAISANCE MEN

To get a sense of the Sagebrush School’s style and works, look no further than its most famous member, Mark Twain. Twain grew into his distinct style during his four years in the state, and his mentor Joe Goodman was certainly a formative influence.

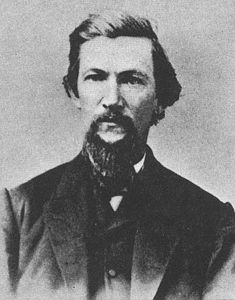

Joe Goodman was one of the most talented writers to work in Nevada. The editor of “The Territorial Enterprise” from 1861-1874, he fostered the career of his friend Twain. He took his work as an editor seriously, and his paper was renowned for fact-based reporting and spotlighting wrongdoing on the Comstock. His reporting exposed corruption in the 1864 Territorial Supreme Court—forcing the bench to resign—, and feverishly rebuked the senatorial campaign of William Sharon—one of the Comstock’s richest men whose morality was sold to the highest bidder.

He was a theater critic, a poet, and a playwright who stood up for journalists under his employment and was known to defend his words with his fists. After leaving Nevada, he became fascinated with Mesoamerican cultures and was instrumental in building the cypher that could decoded the Mayan hieroglyphics.

Another giant of the Sagebrush School was Dan De Quille, whose talent has often been compared to Twain’s. Joe Goodman was fond of both but said that if he were to predict which one would achieve fame, it would be De Quille: “Dan was talented, industrious, and, for that time and place, brilliant. Of course, I recognized the unusualness of (Twain’s) gifts, but he was eccentric and seemed to lack industry.”

De Quille was probably the school’s most prolific writer. Beyond writing for “The Territorial Enterprise” and other western newspapers, he was a novelist who wrote the first major work of the Comstock’s history. Like Twain, he was fond of hoaxes, and his pieces—shared around the U.S.—were praised for their clarity and humor.

There are others who deserve recognition: Sam Davis, Henry Mighels, Fred Hart, Rolin Dagget, and many others. Each worked in a similar style as a beacon of enlightenment, mixing humor and sensitivity with a penchant for seeking truth in the chaotic maelstrom of Nevada’s first few decades.