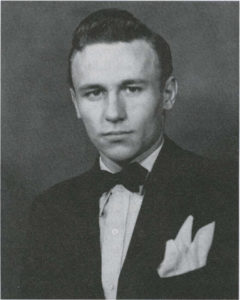

A Preppie in Pioche

Fall 2021

In 1946 a kid from New York gets an education as a mucker and a pitcher in one of the West’s toughest mining towns.

By Ralph E. Pray

After hitchhiking cross-country from my family’s home in New Rochelle, New York, I landed in Salt Lake City looking for a job—any job a husky kid could get. The “men wanted” newspaper ads called for muckers in a Nevada mine. I walked to the hiring office of Combined Metals near my hotel. It was the first of May 1946. I was still a teenager, not long out of Kiski Prep near Pittsburgh.

After hitchhiking cross-country from my family’s home in New Rochelle, New York, I landed in Salt Lake City looking for a job—any job a husky kid could get. The “men wanted” newspaper ads called for muckers in a Nevada mine. I walked to the hiring office of Combined Metals near my hotel. It was the first of May 1946. I was still a teenager, not long out of Kiski Prep near Pittsburgh.

“May I ask what qualifications are required?” I asked the man behind the desk in the office.

”You meet them all,” he answered, leaning back in his desk chair while fishing a smoke out of his khaki shirt pocket.

“But I just walked in,” I said.

”That’s the second part of the requirement,” he said with a smile. ”You have to walk in.”

‘What’s the first?” I asked, more than a little curious.

“Opening the door,” he said. He went on to explain that muckers made $7.20 per shift, with time-and-a-half on Saturdays. ‘We’ll give you a Nevada Lines bus ticket from here to Pioche and take it out of your first paycheck. It’s a five-hour trip.”

”I’m ready to go,” I said, “but I prefer to hitchhike to Pioche.”

I took a bus to the western edge of Salt Lake City and stood with a ready thumb beside the silent highway in white shirt, tie, and sport jacket. I still had $30 in my pocket, enough to live on for two weeks.

The first vehicle going west was the silver-colored bus to Ely. The driver was lonely and picked me up. Later we stopped for a guy standing beside a motorcycle and waving his arms. The three of us hoisted the bike up the bus steps and parked it in the aisle. The road forked at Ely, so I got off there and resumed hitchhiking. An hour later a Ford sedan stopped. The driver and passenger were scruffy looking men in their 30s.

“Hop in, kid. Where ya goin’?” the passenger asked. “Pioche,” I answered. “Got a job in a mine there, working for Combined Metals.”

”That’s where we work. My name’s Charlie. This other drunk’s Sam. Ever work in a mine? You look kinda young.”

“Never worked in a mine,” I answered. ‘Were you shopping in Ely?”

They both laughed. “No,” Sam said. ‘We just got outta the Ely jail. Went on a short drunk. What in hell you wanna work in a mine for?”

”To earn money for travel,” I said.

“Kid, the mine don’t pay money to travel on. Jus’ money to spend. Nobody saves money,” Charlie explained. ‘What goad’s money in the mattress if ya get wiped out in a rock fall?”

A rear tire blew out on the barren stretch north of Pioche. We stopped to inspect the damage. ‘We ain’t got no spare, kid. You can sit over the good tire,” Charlie said. No one could have been more casual about the disaster. We continued driving on the rim at about 50 miles per hour, leaving a gouge in the blacktop and flattening the steel wheel into a small, ugly disk.

The car slowed as we approached the first wooden shacks and modest homes in Pioche at sundown. We passed a man standing limp beside the road. His head was covered with dried blood.

”What happened to him?” I asked, shocked by the sight, my stomach in a knot.

“Don’t know,” Sam said, “but it looks like he got a floater out o’ town.”

”What’s a floater?” I asked.

“If ya get noisy drunk in Pioche, the sheriff arrests ya. If ya can’t cough up the fine and got no friends, they clobber ya real good and tell ya not to come back. Ya walk out o’ town and just float there till somebody takes pity on ya. The law boys hate noisy drunks that’s broke.”

Charlie and Sam dropped me off at a hotel in the business section. As I registered, I noticed five or six friendly ladies, all kind of rough looking, visiting back and forth between the rooms. They were wearing a lot of makeup and tight, revealing attire. The hotel was obviously not just a place to sleep. I minded my own business and found my room.

I cleaned up and went out to see the town. The business section had a long street of saloons, gambling clubs, cafes, and gaudily-painted but untitled doors with curtained windows. The buildings were all wood, some with false fronts, many in need of paint.

The Pioche Club looked like the liveliest place. Inside, I saw a thick blue-smoke haze. As I stepped inside, the smell of whiskey hit me. The place was full of smoke and fumes. I found space at the crap table to place dollar bets. By midnight I had doubled my arrival stake of $30, all in silver cartwheels.

The next morning I boarded the company bus for the 10-mile trip to the Caselton Mine. The mine buildings consisted of a noisy mill, busy shops, a long, V-shaped bunkhouse, and a dining hall, all painted beige. The bus stopped at the bunkhouse. The novelty of arriving at a mine in the Nevada desert as an employee was not lost on me. I was excited.

My work started at midnight, on the graveyard shift, so I had time to snoop around. The bunkhouse reading room had a few shelves of books and several comfortable chairs. A young-looking but bald man was leafing through a magazine when I offered him a smoke.

“Don’t mind if l do,” he responded.

“Can I ask you a couple of questions?” “Sure,” he said hesitantly.

“How long does a paycheck last?” I asked.

“One day usually, one night. There’s enough left over for smokes, maybe a pair of socks, and that’s it.”

“Suppose a miner just doesn’t spend the money. What happens then?”

“He loans it out the next day. We got a few guys like that. But it’s dangerous. You gotta know how to collect on loans. There’s too many ex-cons around here for ya to fool with much cash.”

“How long have you worked here?” I asked.

“Six months. Just about the limit. I’ll be movin’ on. Noticed ya look.in’ at my hair, where it used ta be. I worked in a mercury mine and got poisoned. Lost my hair and my teeth. Got new teeth from the company but no hair.”

‘Thanks for the education,” I said. Back at my room I retrieved my 60 cartwheels. I walked a mile into the raw desert and buried them near a small tree. If someone asked me for money, I could then honestly say I didn’t have any.

That evening, I joined the men going on the graveyard shift. In the change room we removed our street clothes and donned our diggers, which we lowered by chain in a basket from high in the rafters. All the men wore long johns beneath

their diggers.

The men on graveyard were older than the general run of the camp, and I was glad for that. They showed me each step along the way: how to adjust the hardhat fit, how to load carbide granules in my new brass lamp, where the mine shaft was, and when to step onto the man cage to descend into the dark depths.

Deep in the mine the shift boss, Jiggs, handed me a shovel, ‘This is your muck stick, kid. Get married to it.” He showed me where to dig. I began to muck. I was a mucker, the job described in the Salt Lake City paper.

At the end of the shift I placed my damp diggers in my basket and

pulled the chain to raise the muddy mess into the warm upper reaches.

Pop was my roommate. He P was a gray-haired, grizzled man of about 60, shorttempered, slow-walking, and sickly looking. He had silicosis, and his lungs rattled when he coughed. He was a tool nipper, too far gone to do anything but pick up dull drill bits and deliver them to the blacksmith shop for sharpening.

At the end of my second shift I was assigned the job of trammer on the 660-foot level. I pulled overhead chutes of newly mined ore to fill a mine car, pushed the car several hundred feet to a floor grate, and tipped the car to empty it. The rock went down a chute and eventually was transported to the mill, where it was treated to remove sought minerals. The top of each chute was in a stope, where the miners drilled and blasted.

I often climbed a 30-foot ladder into Pete’s stope. He was a miner with a drilling machine and one helper. Every day I’d watch them work and listen to their stories. There was a shiny metal in the ore vein. Pete said, ‘That there’s silver, kid.”

“Can I have a few pieces, Pete?”

“Sure, go ahead,” he said.

I took a little each day, carrying the high-grade ore out of the mine in my pockets and craftily transferring it to my street clothes in the change room and then under my bed in the bunkhouse. I was gloating over my 20 pounds of treasure one day when Pop shuffled into our room. “Kid, what’s that in the box?” he rasped.

“It’s silver from Pete’s stope on the 660,” I said.

‘The company won’t miss a few pounds of it, will they?”

“Kid, this is a lead mine. You work in a lead mine. That’s lead ore there, maybe a nickel’s worth. Don’t listen to those guys,” he scolded.

Pop didn’t have any wind to waste. He seldom spoke. I believed him.

I learned lessons every day, in the mine and above it. There was no place to wear my prep-school blazer, and it remained buried in the bottom of my suitcase. I was not there to be seen. The men I worked with underground included dedicated family men as well as thieves, ex-cons, hermits, old coughing miners, runaway husbands and fathers, down-and-out prizefighters, and full-time drunks. Each day unfolded before me like a fascinating book.

My first payday did not find me at the payroll office. The paycheck remained in the company office. It seemed a good idea to leave all my checks uncashed until the day I quit. I went to my tree on payday and took $5 out of my pillowcase bank. I boarded the bus with the rowdy crew that Saturday night and went to Pioche as an observer of payday at the mines. One other mine had paid on that day, and the town was jumping.

Before midnight the bars and gambling joints had most of the miners’ wages. Short-tempered losers fought in the street in front of the wood buildings. When my five cartwheels were nearly gone on whiskey and dice, I went out to lean against the front of the Pioche Club and watch the bizarre scene.

While I stood in the middle of one of the roughest, hardest-drinking towns in the West, I thought of my family sitting in our spacious house in Rochelle Park. There was a tinge of guilt inside me for the luck I had to be here, a visitor to a different world.

Back inside I nursed a beer as I waited for the midnight bus that would take us back to camp. I was one of the few patrons still sober enough to walk. Gus, the club’s owner, sidled up to me and asked, “Can you pitch softball?”

“Sure, but I’m no speedball artist.”

‘That’s OK,” Gus said. ”You’re our pitcher. The game’s tomorrow at two.”

“You mean the game between Pioche and Caliente?” I asked, recalling the posters up and down the street.

“That very one,” Gus replied with a wink.

After Sunday lunch the bus filled quickly with miners and left for the Pioche ball park. There were 30 or so players and several hundred spectators at the dirt field near the Lincoln County Courthouse.

My catcher was Arky, a smiling, bulky miner from Arkansas on the 600 level. He was missing part of a hand from his time as a Marine on Guadalcanal. He had a few words of advice. “Kid, these things get rough. Don’t take nothin’ serious.”

“Golly, Arky. How can I pitch without bein’ serious?” The notion was beyond me.

‘Jus’ remember I tol’ ya.”

“I see the gloves. What about the bats?” I asked.

“Ain’t but one bat. Lot o’ cracked heads at some o’ these games.”

The wind was blowing fiercely across the ball diamond, carrying gusts of red dust. While I took the mound to warm up, the Pioche people on my right set a beer keg on the players’ bench. The Caliente people on my left were clustered around a keg on the back of a truck. Everyone drank beer out of white paper cups. Several painted ladies from the local cribs were holding beer cups on the Pioche side.

I felt as if I’d stepped into a movie scene, one where everybody had lines to speak, things to do, except me. Some spectators pointed at me, the youngest person at the mine. Many of the men had sons my age far from Pioche.

“Play ball!” the umpire yelled.

‘Throw it, kid,” Arky called.

When l began to pitch, people from both sides cheered. Without my knowing it, we had just progressed beyond the regular scenario. Fights usually started before the game did, and during some Sunday games not a single ball was pitched.

A big gust of wind brought in enough dust to obscure the field. When the red cloud settled I was surprised to see a Caliente player standing on first base. This was a guy who had not yet been up to bat. The plate ump saw the pretender but made no comment. Complaints from the sidelines were mild. Most of the noise was cheering.

Soon I realized this was more of a drinking contest than a ball game. The single bat used by both teams was monitored by a Lincoln County deputy sheriff, a tall, skinny fellow in Levi’s who appeared to be sober. His Stetson was pulled down tight over his forehead to fight off the wind.

“You sure got a funny-looking pitch, kid,” the deputy said. ”Where’d you learn that?”

“Back East,” I answered, not wishing to say words like “New York” in front of so many people. Being from New York was not an asset in this part of Nevada.

The game fizzled out when the beer did. I shook the hand of every player who could stand up. Everyone headed for the parking lot or up to the saloons on the main street.

During the ride back to camp I thought about all the events I’d witnessed on my travels across the country. After escaping an eastern college I had been an iceman in Raleigh, a Walgreen’s soda jerk in Sioux City, a lumberjack out of Portland, a house painter in Santa Fe, a miner in Pioche, and a fascinated observer at all points between. Then I realized how the escape route would lead back to the place where I could quickly learn to manage all these things better—college.

Back at the mine after the ballgame, in the bunkhouse and underground, I was no longer addressed as “Kid.” Everyone called me “Pitch.”